Hohokam Ceramic Studies: Past, Present, Future

This week’s blog is written by James Heidke, Desert Archaeology’s senior ceramic analyst.

Archaeologists have been studying Hohokam pottery for about 100 years. One might think that we would know everything there is to know about the subject by now, but new discoveries are being made in both museum collections and from ceramics recently uncovered during new excavations. The Hohokam are well known for the pottery they made from roughly AD 500 to 1450, which was used for storage, food preparation, cooking, and serving tasks as well as ceremonial purposes. Over the past 30 years, Desert Archaeology employees have analyzed tens of thousands of sherds recovered from hundreds of sites. What have we learned?

The ingredients used to create a pottery vessel include water, clay, tempering materials (which prevent vessels from cracking during drying and/or breaking during firing), colored slips that coat the surfaces of vessels, pigments used in the slip or for decoration, and fuel. Hohokam pottery makers in the Tucson Basin mined clay from areas around their homes, gathered sand from nearby washes, and mined iron-bearing minerals from deposits in the Tucson Mountains that they ground into pigment for the designs they painted or for the coating slips.

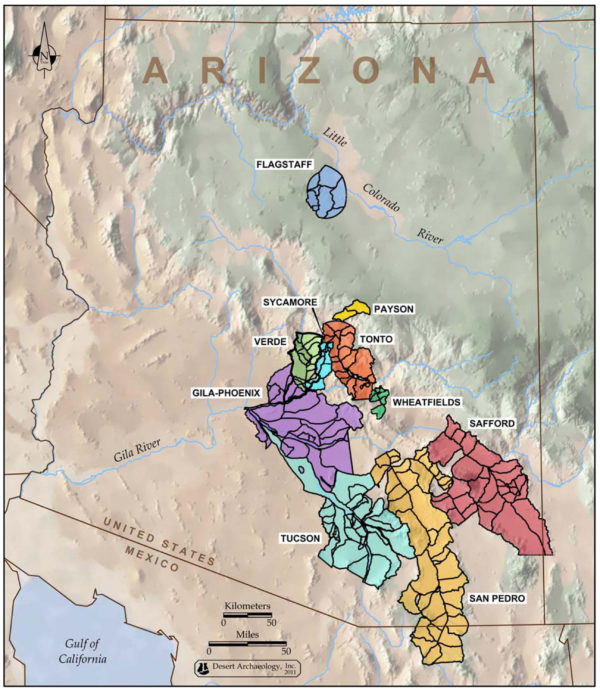

Desert Archaeology has collected and analyzed hundreds of sand samples from locations in the Tucson Basin and identified their distinct rock and mineral compositions. Washes contain sands that erode from nearby terraces and mountains, and their compositions vary throughout the basin based on the geology of the source rock. When examined microscopically (by me with a binocular microscope and by Dr. Mary Ownby with a petrographic microscope), the location of the sand temper source can be determined for most sherds. This has allowed us to trace the movement of pottery across the basin and identify certain villages where large amounts of pottery were made by specialists and then traded for other things, like food or other types of manufactured items.

Desert Archaeology is unique in having collected and analyzed almost 1,500 sand samples throughout Arizona. This has allowed us to identify many petrofacies in 11 different regions. For these areas, we can reconstruct social and economic networks based on the movement of ceramics.

Pottery was made using coils of clay that were bonded and thinned using a paddle-and-anvil technique. Polishing stones were used to smooth the surfaces of pots (my colleague Dr. Jenny Adams can identify polishers due to the distinctive wear present on them). Historically among the O’odham people—descended from Hohokam groups—the women made pottery vessels, and it is likely that Hohokam ceramic production was under the control of women as well. At the Yuma Wash site in Marana, we excavated a mortuary feature containing the remains of an older woman (aged 45 to 55 years at death) lying on a layer of broken, unfired storage jar sherds. Among the many artifacts buried with her were a metate, four lapstones, two pieces of hematite pigment, a handstone, and two polishers—probably the tools she used to manufacture vessels.

A 1907 photograph by Edward S. Curtis, “A Papago Potter,” shows an O’odham woman making a vessel using a paddle.

Sometimes we find evidence for pottery production in structures. Desert Archaeology excavated a portion of the Julian Wash site prior to the construction of the Interstate 10 and 19 interchange. On the floor of Feature 303, a Middle Rincon phase (AD 1000-1100) pithouse, were 15 vessels, four of which were unfired. Of particular interest is that the unfired vessels had different surface treatments: two were undecorated, one was covered with a red slip, and one was painted with a red-on-brown design. A single potter was apparently decorating vessels in different ways. Also found were four lumps of red ochre pigment, three polishing stones, and a lump of micaceous schist or gneiss that could have been used as a tempering material. In an upcoming blog entry, I will be discussing a recently excavated house found at the Pima Animal Care Center project that contained abundant evidence for pottery manufacturing.

Pithouse Feature 303 at the Julian Wash Site, with fired (gray) and unfired (brown and eroding) vessels on its floor.

Firing vessels would have been a difficult and time-consuming task. We have not found evidence for in-ground kilns. It appears that the Hohokam instead fired their vessels by placing them on the ground surface inside a pile of wood. My colleague Henry Wallace believes that each Hohokam household probably used between 35 and 50 ceramic vessels each year, with cooking and serving vessels breaking rather frequently due to their repeated exposure to fire or frequent handling, while storage vessels would have lasted longer because they were not moved as often.

Reuben Naranjo’s 2002 University of Arizona master’s thesis looked at historic period O’odham pottery production, using nineteenth-century newspaper accounts to identify the times of the year pottery was made, work that I have continued. O’odham women made pottery during seasons when there were few wild or domesticated foods to harvest and when there was little rain to cause problems with drying or firing, from late January through early June and, rarely, from early November to late December. It seems likely that prehistoric Hohokam women followed this schedule as well.

Painted designs first appeared on Hohokam pottery around AD 500. These designs changed over time, similar to the way clothing styles change today. Radiocarbon dating of contexts in which decorated pottery has been found has allowed archaeologists to identify the date of sherds based on design elements, usually within 50- to 100-year time spans. As an example, during the Colonial period (AD 750 to 950) many naturalistic elements (mammals, birds, flowers) were painted in banded designs on pots.

A Cañada del Oro phase (AD 750 to 850) sherd from the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson, featuring a naturalistic flower design.

Later, that kind of design layout fell out of favor and Hohokam potters focused on geometric, basket weave-like designs. The shapes of vessels and the location of the painted designs on them can also be used to date ceramics. Based on the study of decorated pottery from stratified contexts, my colleague Henry Wallace has been able to develop fine chronological distinctions among the designs, allowing for the closer dating of archaeological features.

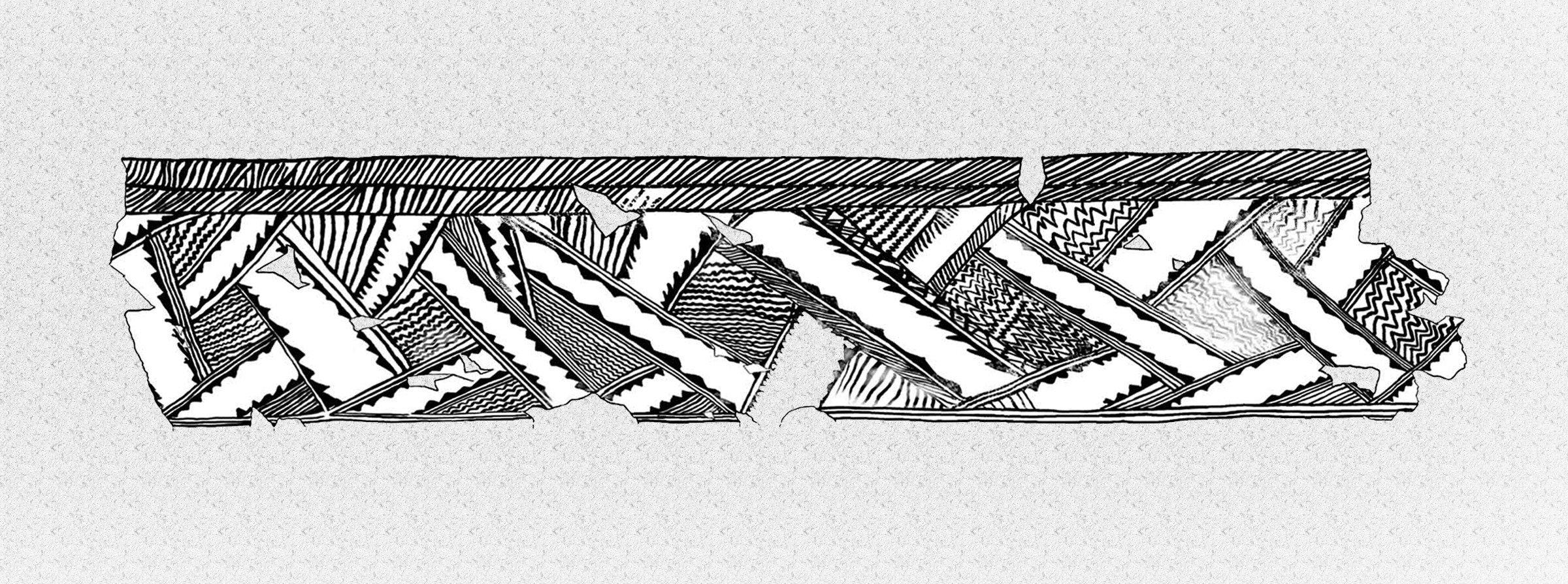

Tanque Verde phase (AD 1150-1300) sherds from the Mission Garden locus of the Clearwater Site located near A-Mountain, with geometric, basket weave-like designs.

I collect information on the many small design elements seen on Hohokam ceramics. Those designs were likely passed down from mother to daughter (or daughter-in-law?), and by looking at the location where a pot were made (determined through temper characterization and petrographic analysis), we can trace the movement of women from one settlement to another.

The data encoded in the materials, vessel forms, and painted designs of Hohokam pottery continues to provide us with new information—and provides modern Tucsonans a means by which to better understand the daily lives of those who lived here before them.

The image at the top of this post is a rollout illustration of the design on a Late Rincon Red-on-brown vessel from Honey Bee Village, drawn by Rob Ciaccio.

Resources

Many of James Heidke’s publications are available as PDFs on his Academia page (site registration is required, but is free).