Funeral Bills and Coroner’s Inquests: The Other Block 92 Scandal

Historical archaeologist Homer Thiel continues the story of 19th-century Tucson’s scandalous Block 92.

A previous blog post chronicled the scandalous history of Block 92 resident Jack Boleyn. As a historical archaeologist, I use documents (deeds, court records, maps, photographs, newspaper articles, etc.) along with archaeological features and artifacts to reconstruct the lives of largely forgotten people. While researching the history of Lot 12 of Block 92, I found that Boleyn’s neighbors had their own scandal.

George L. Johnson (born circa 1839 in Massachusetts) and his wife Ada Eliza (Hall) Johnson (born circa 1842 in Illinois) purchased Lot 12 in 1889. This lot fronted 11th Street, today E. Broadway Boulevard, at 5th Avenue. Ada previously had been married to a Mr. Hall, with whom she had a daughter, Lillian, born in the late 1860s.

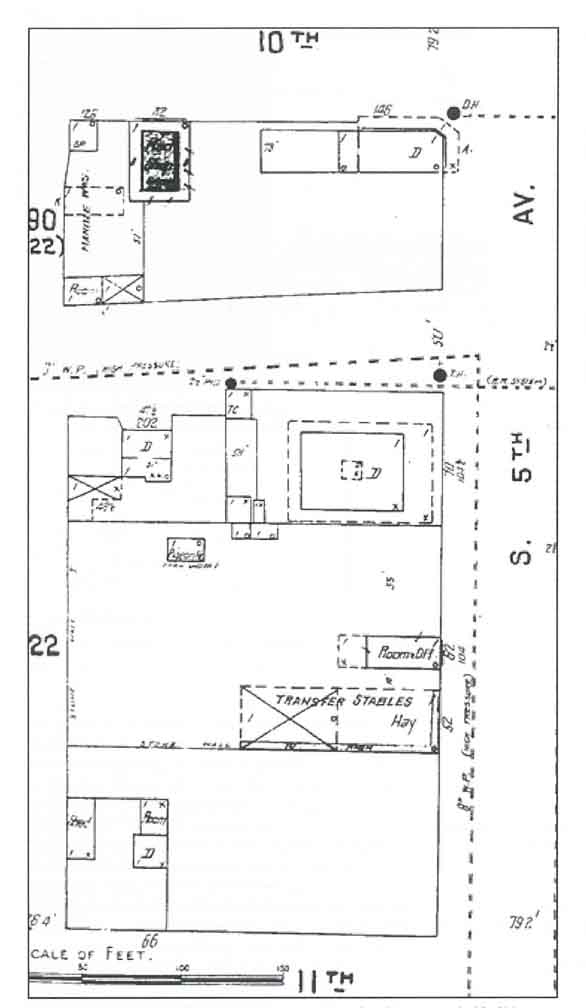

The Johnsons built a house on Lot 12 in the early 1890s, set back from the street, with a small stables and an outbuilding nearby. George worked as a miner in the mid-1880s, although his occupation by the 1890s is unclear. He was a member of the Tucson volunteer fire department, headed by Fire Chief Jack Boleyn.

1901 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of the east half of Block 92 in downtown Tucson. The Johnson house is at the lower left corner. 11th Street today is E. Broadway Boulevard.

Ada’s daughter Lillian Hall was married in 1883 in Tucson to William Hopkins, and the couple had a son Rupert (nicknamed Rube) in 1887. Lillian and William separated and may have divorced (a divorce record has not been found). Lillian married a second time in 1893, to Robert B. Canon. The couple quickly developed problems and by 1895, Lillian was back living with her parents.

George and Ada sold the lot in late June 1895. The reason why? On June 1, 1895, Robert Canon and his friend Riley Anderson had shown up at the Johnson house, drunk from a 25-cent bottle of whiskey purchased at Tapia’s Saloon. Ada Johnson earned money by doing laundry and had a package of Anderson’s shirts ready to be picked up. Canon loudly called for the shirts and then demanded that his estranged wife, Lillian, come back home, shouting that if she didn’t he would kill her. Lillian begged her mother to put him out of the yard. Robert called her a “damned bitch.” Lillian threatened to shoot him, and went inside and picked up her shotgun, which she used to hunt birds. Robert called out, “You son of a …” and she shot him in the right arm.

Canon fell down. A Dr. Matas was called and could not stop the bleeding (other historical records suggest he apparently was a terrible doctor). Dr. Hiram Fenner (who in 1898 would purchase the first automobile in Tucson) was then called. Fenner had Canon loaded into a wagon to be taken to St. Mary’s Hospital, but Canon died on the way.

Lillian was arrested and charged with assault with intent to murder. A coroner’s inquest was held and the verdict was that Robert Canon had died from a gunshot wound inflicted by Lillian Canon. She was ordered held in jail with a $10,000 bail. Her parents likely sold Lot 12 to pay her legal fees.

By October 1895 Lillian was out on bail, and the trial was held in December 1895. A transcript of the trial apparently does not survive. A newspaper account reveals that the prosecuting attorney told the all-male jury that Lillian had to be found guilty unless she had acted in self-defense. The jury subsequently found her not guilty and cleared her of the charges.

Lillian wasted no time and married again in February 1896, to a miner named Miles Taylor. She gave birth to a son in December 1896. Meanwhile, her mother and stepfather bought back their house for a dollar, returning to Block 92 to live.

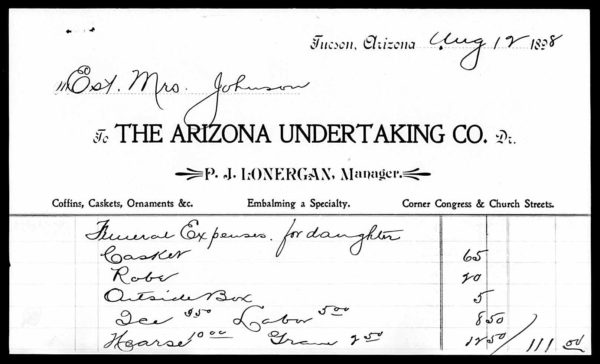

Ada Johnson died in June 1898. Her probate file includes her funeral bill from the Arizona Undertaking Company: $75 for her casket, $5 for the outer wooden vault box, $45 for a robe, $3.50 for ice (to help preserve the body), $5 for labor, $10 for the hearse, and $4.50 for digging her grave in the Court Street Cemetery.

As for Lillian? The same probate file contains bills for the funerals of Lillian (below) and her infant son, who both apparently also died in 1898. The funeral bills are the only records found to date that reveal the fate of these two individuals.

George Johnson subsequently borrowed money from businessman John Ivancovich, and after he could not pay back the money, Lot 12 was ordered sold. George died in 1908 from kidney disease and was buried with his family members in the Court Street Cemetery.

Our archaeological work on the block found a few traces of the Johnson house and a few planting pits that yielded artifacts and food remains. The recovered items provided little information on the family, which sometimes happens. In this case, historical documents revealed the details of Lillian (Hall)(Hopkins)(Canon) Taylor’s scandalous life.

This research was conducted for 5 North Fifth Hotel, L.L.C. Today the AC Marriott Hotel is nearing completion on the site of the Johnson home.