It’s Getting Hot Around Here! The 2017 Southwest Kiln Conference

Desert Archaeology ceramic petrographer Mary Ownby writes about the innovations and experimentation inspired by this year’s pottery conference.

The annual Southwest Kiln Conference was held in early August in Tijeras, New Mexico. This event brings together a wonderful group of people interested in prehistoric pottery. A number of the individuals make replications of the pottery using traditional techniques, including mining their own clays, paints, and slips, hand-building the pots, painstakingly decorating them, and firing them in either trench or pit firings. The resulting vessels are astounding in their veracity and just plain beautiful to behold!

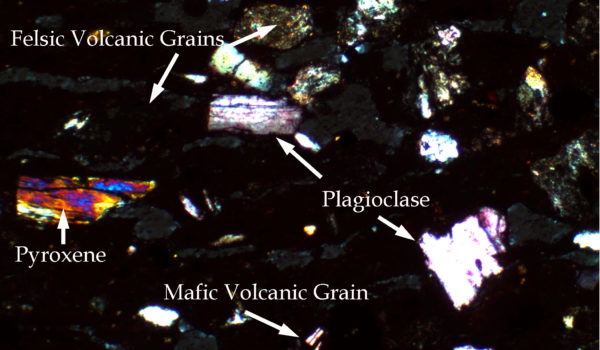

This was my third year to attend the conference. The first year I presented on how petrographic analysis of ancient pottery helps researchers understand how it was made, from the exact raw materials used to the firing temperature and atmosphere. Surprisingly, the group was very enthusiastic about this somewhat esoteric and specific way to look at pottery. They invited me back the next year, and this time I brought my small microscope with me so they could look at thin sections of pots too. As is normal, when a person first looks at pottery under high magnification, they were blown away by the color and variability of the sands visible within the thin section—it is a whole world in there, as I usually say!

The world of microscopic sands locked inside the walls of ceramic vessels, visible when a thin section is sliced from the pot and viewed under a petrographic microscope.

For my third time at the Southwest Kiln Conference, I wanted to introduce the attendees to a new analytical technique. Through the generosity of Lee Drake (PaleoResearch Institute) and Katharine Williams (University of New Mexico), a portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometer was brought out to this year’s conference. This equipment provides qualitative data on the chemical compositions of clay surfaces, slips, and paints.

Mary Ownby, center, watches as the beam from a portable X-ray Fluorescence scanner is aimed at a sample.

We examined 45 samples, including raw slip and paint nodules. The results indicated a diversity of materials, especially for the raw paint minerals. Of keen interest was the comparison of mineral paint to experimental organic paints made from Rocky Mountain Beeweed. We found that the mineral paints are high in iron, lead, and manganese, while the organic paints have notable potassium and calcium levels in addition to manganese—information that may be helpful for researchers studying the composition of paint on vessels from archaeological contexts.

Rocky Mountain Beeweed can be boiled down into a thick black liquid. It has been used for centuries in the Southwest to make black paints such as those used for the designs on these pots from Aztec Ruin in southwest Colorado (National Park Service photo).

While such data are interesting and help the potters to know their materials better, the goal of this conference is discussion and experimentation. We had a wonderful time discussing the various outcomes of test trials and how they inform our understanding of past potters’ behavior. For example, Andy Ward has been mining clay he thinks was used for making Salado Polychrome pottery in southeastern Arizona. He then creates replication pottery with white slips and organic black paint made from a variety of materials. Andy has perfected a firing technique for these pots so that the red slip is oxidized and the black organic carbon paint isn’t burned off. He creates a bed of coals, places the pots on top and then stacks wood vertically around them. They fire up to 800°C (Andy uses a thermocouple to monitor the temperature), which is the temperature most pottery reached prehistorically.

Firing pots at the scenic Tijeras, NM Ranger Station with fellow ceramic enthusiasts at the Kiln Conference.

I have also used the vast knowledge and benefit of discussions at the kiln conference to embark on my own experiments. I have used a number of different clays to create horrible little pots using paddle and anvil (Hohokam technique) and coil and scrape (greater Pueblo technique) to test how the clays perform under the different forming methods. I even did a small pit firing in my backyard and found out why a bed of coals is good idea—I had instead placed my pots on pieces of sandstone over wood that then smoldered and sooted the pots, which did not improve their terrible appearance). Overall, the experiments revealed that primary clays (excavated from the source rocks) are good for coil and scrape, while secondary clays (developed in soil deposits far from the source rocks) are ideal for paddle and anvil. Indeed, my petrographic studies have shown these are the types of clays often used with the different forming techniques by ancient potters.

These conferences are wonderful opportunities to learn from replicating potters, gain inspiration, and discover much about past pottery practices.

Interested in learning traditional pottery techniques? Visit the Southwest Kiln Conference website to find out about upcoming workshops offered by master potters throughout the Southwest.