Well-Seasoned: Historical Perspectives on Precontact Pottery Making

What started out as a reexamination of schist temper led Desert Archaeology ceramicist James M. Heidke to review evidence regarding the time of year precontact pottery may have been made.

Fontana and others found that mid-20th century Tohono O’odham potters only made vessels during the hot summer months, both for their comfort and to let unfired pots dry in the sun. However, mid-to-late 19th century and early 20th century accounts contradict this finding, which in turn has implications regarding precontact ceramic manufacture. For example, Fontana and others’ statement figures prominently in Frederick “Fred” Huntington’s argument regarding seasonal pottery manufacture at the West Branch site, AZ AA:16:3(ASM), during the Tucson Basin Hohokam Early and Middle Rincon phases (c. AD 950-1100).

Abundant evidence for pottery making was recovered from West Branch (south of West Ajo Way along South Mission Rd) in 1984, but perhaps most noteworthy was that from the floor of burned pit structure Feature 1199. A potter’s anvil, five pottery polishing stones, a fragment of a tabular knife stained with red pigment, a fragment of an oval handstone exhibiting battering marks and red pigment stains on one end, four piles of schist temper in different states of reduction, and a large ball of processed caliche, inferred to be white slip, were found on that floor.

Processed schist temper recovered from the floor of West Branch site Middle Rincon phase Feature 1199. Four coarse gravel-sized pieces of schist (top left), 15 medium gravel-sized pieces of schist (top right), fine-to-very fine gravel-sized schist (large cap, bottom left), and sand-sized schist (small cap, bottom right).

Based on Fontana and others’ finding that pottery production was an activity that only occurred during the summer, Huntington reasoned that the house must have burned at that time of the year. A single saguaro cactus seed was recovered from the structure’s hearth. Since saguaro fruit is gathered in the late spring or early summer, its presence supported the idea that the house must have been destroyed when that resource would have been available.

But how could Huntington’s interpretation be evaluated? Newspaper stories, other reports and historical weather records were the keys. At least 55 accounts of Tohono O’odham and Piipaash pottery manufacture or distribution were published between 1849 and 1927, primarily in the Arizona Daily Star, Arizona Citizen, Arizona Weekly Citizen, Arizona Republican, Bisbee Daily Review, Tombstone Epitaph, Tombstone Prospector, Tucson Daily Citizen, and Weekly Orb. Although most of these stories discuss distribution-related activities, sixteen observations of pottery making are interspersed throughout.

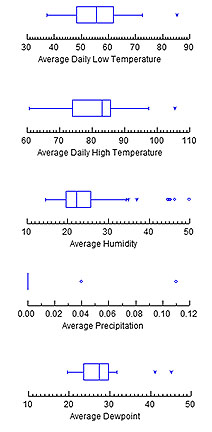

Temperature, humidity, and precipitation data for the days with reported ceramic production and/or distribution events were downloaded from an online weather database on January 30, 2013. Tucson readings were taken from the San Xavier Indian Reservation data set, which at that time had 53 years of records. Bisbee and Tombstone readings were taken from the Tombstone data set, which had records for 118 years. The meteorological data indicate that Tohono O’odham and Piipaash potters preferred working conditions when the average low temperature was greater than 37°F, the average high temperature was less than 97.5°F, the average relative humidity was between 14.5 and 50 percent (generally less than 34.5 percent), the likelihood of precipitation was low, and the average dew point was less than 32°F.

Box-and-whiskers plots of meteorological data. Vertical line in box indicates median average value.

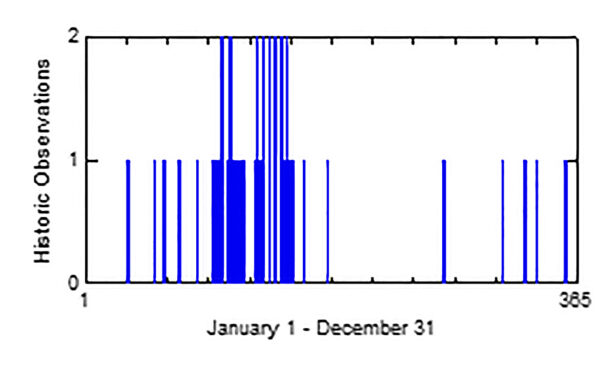

Expressed as an annual cycle, the first observation of pottery production (February 1) occurs just a day after the first observation of distribution (January 31), while the last observation in the series is one of production (December 22).

Published accounts of pottery making and/or distribution expressed as an annual cycle.

The published accounts indicate that pottery making was a seasonal activity that took place sporadically from late January through late March, commonly between early April and mid-June, and again sporadically from early November through late December. Notably absent from the accounts are observations during the monsoon season, defined as running from June 15 to September 30 (following the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration protocol that went into effect in 2008), when the probability of precipitation is 20 percent or greater. Only one distribution event was documented during that span (June 29) and one case of pottery making (September 23).

Four additional sources are less specific temporally but support the newspaper accounts. First, Frank Russell’s series of photographs showing clay mining and pottery forming, decorating, and firing must have taken place sometime between January and June, given that he spent November 1901 through June 1902 on the Gila River Indian Community and his photographs were taken in 1902 (Negatives 2653 B-C, 2654 A-B, 2655 A-C, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution).

Akimel O’odham potter photographed by Frank Russell in 1902. Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives GN 2655B, downloaded July 11, 2013.

Second, a H. Buehman and Co. studio portrait of two Tohono O’odham women with kiâhâ (carrying baskets) containing ollas is dated May 5, 1883 (Photo Lot 90-1, number 140, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution). However, as that photograph is a studio portrait, there is no way to confirm that the women were in Tucson on that day to distribute pottery. Third, a photograph by William Dinwiddie dated November 1894 shows another Tohono O’odham woman about to lift a kiâhâ containing at least four black-on-red jars (GN 02749B, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution). Finally, Fontana and others cite the unpublished 1894-1895 notebooks of William J. McGee wherein he mentions O’odham potters working near Hermosillo, Mexico during the month of November.

The published accounts are at odds with Fontana and others’ finding regarding pottery manufacture occurring during the hot summer months, but what of the saguaro seed recovered from the hearth of the West Branch house? Saguaros bloom from late April into June, with their fruit maturing from late May through early- to mid-July. Each mature plant can produce 150 to 200 fruits, and each fruit can contain up to 2,500 seeds that each measure just 1.5 mm (0.06 inch) long. Traditionally, saguaro fruit was harvested and processed in June and July. Sun- and air-dried and then parched, their protein and oil-rich seeds were also collected at that time for later use. In fact, paleoethnobotanist Charles Miksicek documented more than 1,150 uncarbonized saguaro seeds in deposits more than 50 years old recovered in 1982 from an Historic household at archaeological site AZ AA:13:19(ASM) within the modern village of Nolic on the Tohono O’odham Nation.

Their tiny size and documented potential for storage suggests that the recovery of a single saguaro seed from a hearth flotation sample can neither confirm nor deny the season that the West Branch structure burned. The point of this Field Journal entry, then, is not that Huntington must have been wrong in following Fontana and others in concluding that pottery making occurred during the summer, but, rather, that another explanation appears to be equally valid. Potting may have commonly occurred during the spring and the saguaro seed found in the hearth may have been brought to the site and then stored.

Those interested in learning more about traditional use of the saguaro cactus may find the following to be useful:

Frank S. Crosswhite (1980) The Annual Saguaro Harvest and Crop Cycle of the Papago, with Reference to Ecology and Symbolism

Rebecca S. Toupal, Henry F. Dobyns, and Richard W. Stoffle (2006) Traditional Saguaro Harvest in the Tucson Mountain District, Saguaro National Park

Enrico Ceotto (2009) Cultivation of Carnegiea gigantea from Seeds: a Journey in Desert Ecology