Native American Pottery in Historic Period Tucson

Desert Archaeology’s ceramic analyst Jim Heidke writes this week’s blog.

In 1958, four graduate students (Bernard Fontana, William Robinson, Charles Cormack, and Ernest Leavitt, Jr.) took a seminar from Dr. Emil Haury at the University of Arizona. They chose to study historic period Native American pottery, specifically, Papago ceramics. At that time the Tohono O’odham were referred to as “Papago,” a name that is no longer used. Over the next two years the four men researched historical documents, interviewed living Tohono O’odham potters, and examined ceramic sherds and whole pots held at the Arizona State Museum.

In 1962, the University of Washington Press published their book, Papago Indian Pottery, describing what was then known about ceramics made by these Native American potters. In 2002, Reuben Naranjo’s master’s thesis at the University of Arizona, Tohono O’odham Potters in Tombstone and Bisbee, Arizona- 1890-1920 (2002) provided new insights into the manufacture and sale of Native American pottery.

In 1962, the University of Washington Press published their book, Papago Indian Pottery, describing what was then known about ceramics made by these Native American potters. In 2002, Reuben Naranjo’s master’s thesis at the University of Arizona, Tohono O’odham Potters in Tombstone and Bisbee, Arizona- 1890-1920 (2002) provided new insights into the manufacture and sale of Native American pottery.

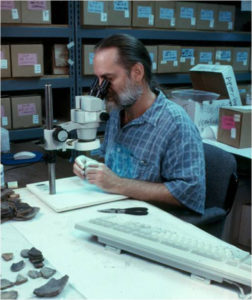

Excavations in Tucson by Desert Archaeology have resulted in over 30 well-dated collections of historic Native American pottery that I have studied these using techniques and samples not available to the 1950s graduate students. This research adds to the prior work and has uncovered significant new information about O’odham ceramic manufacture between the 1770s and 1920s, and how the people in Tucson used those ceramics.

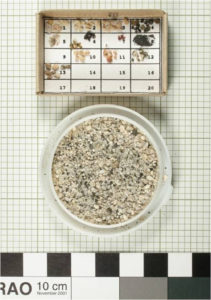

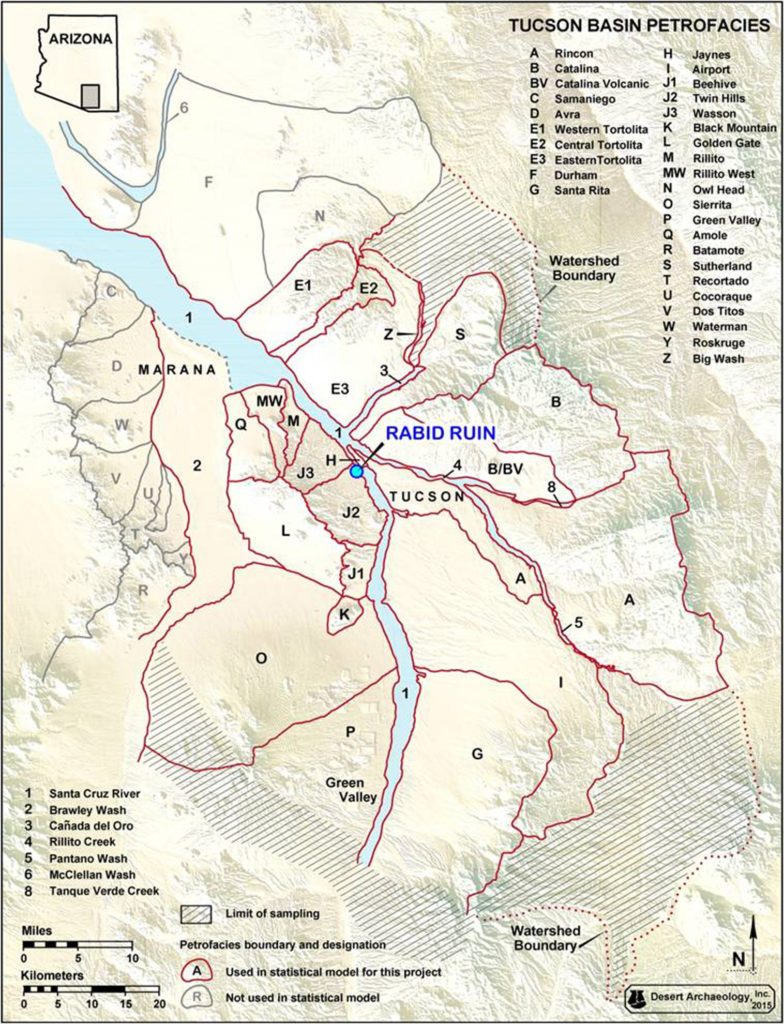

Desert Archaeology has collected and analyzed sand samples from hundreds of locations within the Tucson Basin. The sand found in washes varies dramatically from place to place, containing different kinds of rocks and minerals depending on the source rocks for the sand comes from (see Mary Ownby’s blog, Petrography and Archaeology: Microscopic Fun with Pottery). Potters collected sand for use as tempering material, mixing it into the clay to keep vessels from exploding as they were fired. Studies of modern potters have revealed that they usually collect sand within three kilometers (~1.9 miles) of where they live.

I look at sherds under a microscope and identify the location where the tempering sand in each was collected. I have found that pottery manufactured during the Spanish, Mexican, and early American Territorial periods, from the 1770s to the early 1870s, used sand from the Tucson Mountains as a tempering material. This suggests the potters were living close to downtown Tucson. This time period also saw the first use of organic material—manure—as a pottery temper, resulting in a distinctive black core. The San Xavier Reservation was established by the United States government in 1874, and soon thereafter there was a marked increase in pottery manufacturing near the San Xavier Mission, a result of potters moving to the reservation.

Sand-tempered plain ware sherd from the Spanish-Mexican occupation at San Agustín Mission (left) and sand- and manure-tempered Papago Red sherd from the American Territorial period occupation of the Gallardo and Carrillo households in Tucson (right).

At about the same time more vessels, mostly jars, were covered with a red slip on their exterior surface. Many of those jars were used for water storage. The porous pottery allowed water to slowly seep through and evaporate on their exterior, helping to cool the contents. Newspaper stories reveal that the pots generally held between three and five gallons of water and usually cost about $1.00 at the time (or $25.75 in 2016 dollars). They were popular in the days before indoor plumbing, when water was sold door to door from a tanker wagon. A few modern residents remember drinking water from these pots and note that people preferred the taste of the water, describing it as being “seasoned.”

Olla from historic Block 83 showing the black core from the use of organic tempering material (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

The Spanish and Mexican soldiers and their families at the Tucson Presidio had a hard time obtaining the iron and copper vessels they were used to, as the nearest stores at Imuris and Arizpe were over 100 miles away. They needed griddles (comales) for frying wheat and corn tortillas and chocolate pots (chocolateros) for making a hot chocolate drink that was a breakfast staple. Excavations at the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson and the León Farmstead resulted in the recovery of ceramic comales and chocolateros manufactured by the O’odham.

Fragments of Native American pottery comales found during excavations at the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson (photo by Homer Thiel).

A Papago Black-on-red chocolatero pot from the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson.

These types of vessels were not made prior to the Spanish entrance into the area, and reveal that the O’odham adapted their pottery making skills to meet the needs of the Presidio residents. Presidio women also used O’odham bean pots to cook soups and stews in, replacing hard to obtain iron or copper cooking vessels.

Historic photographs show O’odham women bringing burden baskets filled with Native American pottery into Tucson. Newspaper article research has revealed that O’odham potters usually made vessels from late January through early June and again, occasionally, from early November through late December. Once made, women carried the pots into town and sold them door-to-door. As noted by Reuben Naranjo, potters worked during times when there were no wild or domesticated foods to harvest and when there was little chance for rain to interfere with vessel production.

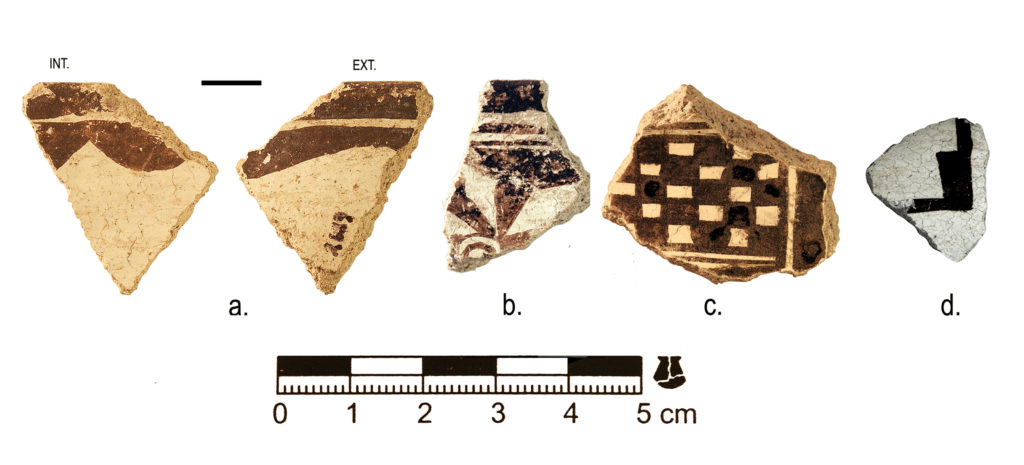

Occasionally we find Native American pottery made outside of southern Arizona. A few pieces of Zuni and Acoma pottery have been found at the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson. In 1793, Comandante Jose Romero led an expedition north to Zuni and it appears that several of the soldiers brought pottery back, perhaps because their black-on-white decorations were so different from the local O’odham ceramics.

Zuni and Hopi sherds from vessels brought to the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson by Mexican soldiers.

A much later outhouse pit, dating from 1900 to 1910 on Block 91 in downtown Tucson, yielded fragments of a Sikyatki Revival seed jar made by a Hopi potter. The late 19th and early 20th century saw the beginnings of Native American pottery production for the tourist trade, and this pot was perhaps a souvenir that was broken and discarded.

Each historic site excavation has the potential for new discoveries about historic Native American pottery. Desert Archaeology has developed strategies to recover substantial information from the scraps of discarded broken pots.

Resources

An article from Jim on historic Tohono O’odham ceramics written for popular audiences can be found in this back issue of Archaeology Southwest Magazine (p. 21).

Jim’s technical reports on historic Native American pottery include research from sites excavated during the Rio Nuevo and Paseo de las Iglesias projects in Tucson, as well as work along State Route 260 east of Payson, Arizona (free site registration required).