A Tale of Two Parks

Many of the public parks currently enjoyed by Tucson residents lie on parcels of land whose history goes back hundreds of years. Historical archaeologist Homer Thiel explores some of the hidden history uncovered by Desert Archaeology in two very different parks located at different edges of the Tucson Basin… and tied together by a single 19th-century family.

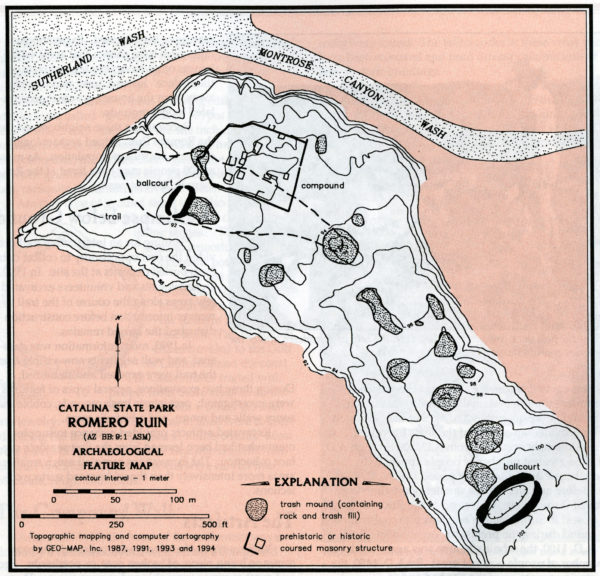

Catalina State Park was established in 1983. Located in the western Catalina foothills north of Tucson and east of the town of Oro Valley, the park has both natural and cultural resources. Desert Archaeology conducted a survey of the park to document archaeological sites, including the Romero Ruin. This multi-component site includes Hohokam trash mounds, a compound with structures, and two ballcourts.

The extensive prehistoric occupation of Romero Ruin is indicated by several trash mounds, two ballcourts, and the remains of stone structures within a walled compound.

The Hohokam began to construct ballcourts around AD 750 and continued to do so until about AD 1000. These were large, oval-shaped depressions surrounded by earthen embankments. The interior are often smoothed, sometimes plastered, and sometimes have stone markers embedded in them. It is thought that some sort of ball game was played in the courts. These games may have drawn visitors from surrounding areas, allowing people to gather to have a feast, to trade, and to look for marriage partners.

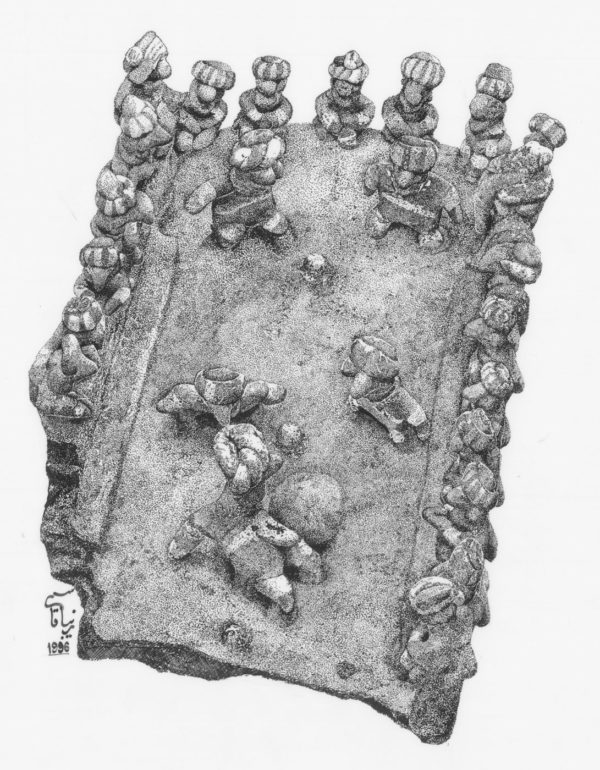

Historic accounts from the first Spanish incursions into Mexico relate games played with rubber balls in courts similar to those found in southern Arizona. Rubber balls have been found in southern Arizona as well. This drawing illustrates a game depicted on a prehistoric ceramic piece from Nayarit, Mexico. Illustration by Ziba Ghessemi.

Artist’s reconstruction of a game in progress in a ball court near Tucson. Illustration by Rob Ciaccio.

The people who built Romero Ruin’s ballcourts a thousand years ago lived in masonry structures surrounded by a compound wall atop a ridge. Five mostly fallen-down stone structures that are visible within the compound are more recent. Francisco Romero built them, probably in the 1870s, with the largest likely serving as his ranch house. Francisco was born in Tucson in 1822. He was married prior to 1853 to Victoriana Ocoboa, who was born around 1833 in Tucson.

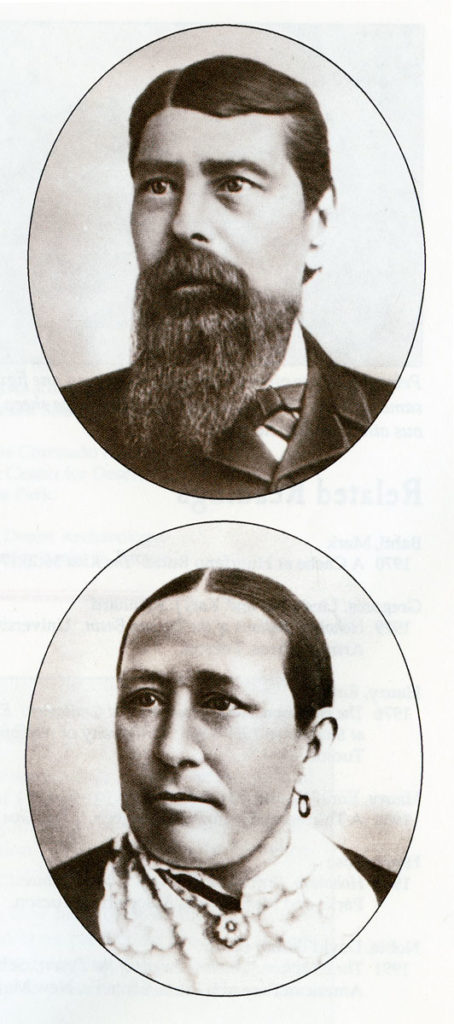

Francisco Romero and Victoriana Ocoboa de Romero. Photos courtesy of the Arizona Historical Society.

While Francisco served in the Mexican army in the 1850s, he and Victoriana built a house just outside the northwestern corner of the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson, in what is now downtown Tucson. They also owned agricultural fields on the floodplain of the Santa Cruz River to the west. They likely built the ranch in what became Catalina State Park to help manage a cattle herd. However, they were forced to abandon the endeavor because Apache raiders kept attacking the ranch. Francisco’s son later said that the Apache would capture cattle at night and Francisco would chase after them, armed with a brace of pistols and a rimfire .44 carbine. A grandson reported that Francisco’s body was scarred from arrow and lance wounds suffered during these forays.

Arizona State Parks’ plans to build a trail through the Romero Ruin led to an archaeological data recovery project, conducted by Desert Archaeology Project Director Deb Swartz. She excavated units in the largest, two-room building and found that it had a corner fireplace. Few artifacts were found, probably reflecting the short span of time the Romero family spent here.

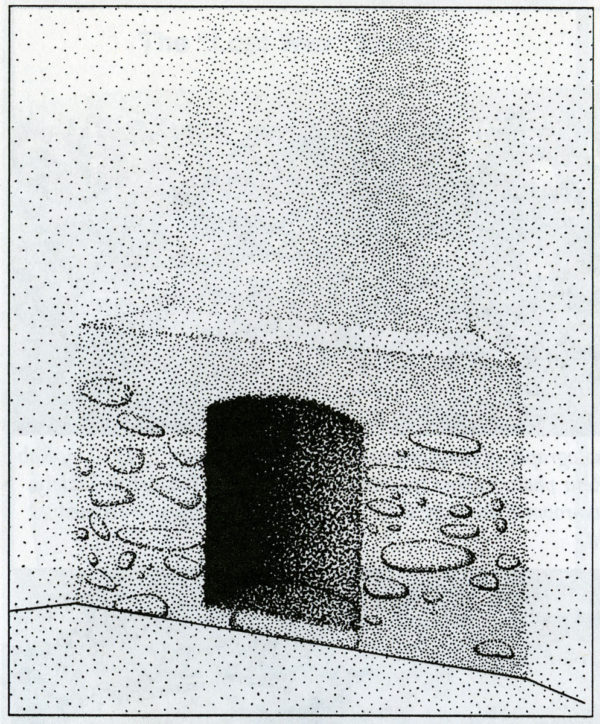

A corner fireplace was found in the excavated room. Archaeologists observed very little fire-blackening on the stones, another clue that the occupation was short-lived. Because rocks remained in place only to the level of the fireplace opening, the shape of the chimney above is conjectural.

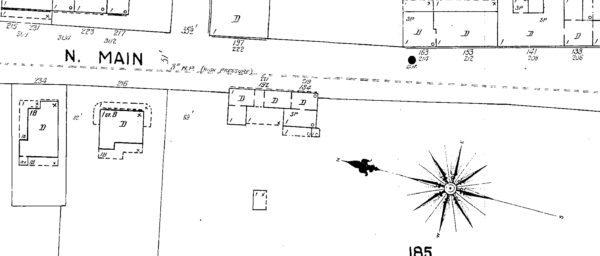

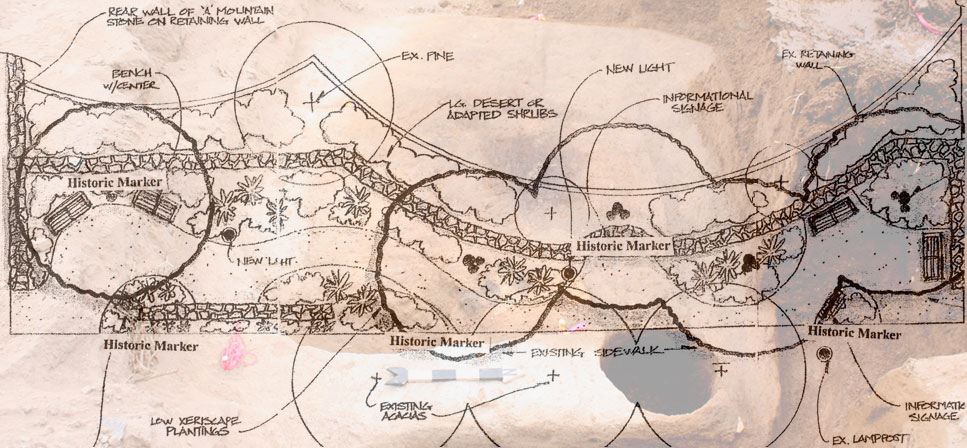

In 2012, private citizens raised money for a small pocket park, Christopher Franklin Carroll Centennial Park to commemorate Arizona’s 100th birthday and a local resident. The park is located on a small strip of undeveloped City of Tucson land downtown at the southwest corner of N. Main Avenue and W. Washington Street. Before construction took place, Desert Archaeology excavated a pair of backhoe trenches at the north and south end of the planned park, finding soil layers with artifacts and a Presidio-era soil mining pit. We also dug three 1×2 meter excavation units. Two came down onto a rock foundation, which we subsequently uncovered.

This turned out to be the house of Francisco and Victoriana Romero.

The house originally was on the west side of Calle Real, which later became N. Main Avenue. The rock and mortar foundation was at least 22 m long, north-south, and was divided into four rooms, the same number as depicted on the 1901 Sanborn Fire Insurance map. Adobe walls once stood on the foundation. The house was present in 1862 and was torn down between 1904 and 1909, perhaps sometime after Francisco died in 1905 or when Victoriana died in 1908.

Behind the house an horno oven base was found. During the Presidio-era (1775-1856) and into the early Territorial era, people built domed adobe brick ovens next to their homes, as it was too hot to have an oven inside the house. A fire was built inside the oven, heating the bricks. When the exterior felt very hot, the coals and ashes would be drawn out, the inside quickly mopped out, and the wheat bread dough placed inside. A wooden door, covered with wet cloth, closed up the oven. At the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson Museum, a loaf of bread takes less than a half hour to bake in the replica horno during living history demonstrations. One can imagine Victoriana Ocoboa de Romero baking bread for her husband and children in the oven.

The horno at the Presidio San Agustin del Tucson is used to bake bread during Living History events.

The base of the Romero house horno. The bricks are fired bright red from the extreme heat of the oven (photograph by Homer Thiel).

After our work was completed, Centennial Park was built. Three interpretive signs installed there tell the story of the neighborhood, focusing on irrigation, the Presidio, and the mansions that line Main Avenue. Beneath the surface are the physical remains of the Romero home, telling another story.

Resources

Desert Archaeology’s report on the downtown Romero house is available as a free PDF.

A description of the interpretive trail leading to the Romero Ruin is available on the Catalina State Park website.

A limited number of booklets detailing the Romero Ruin and other cultural resources in Catalina State Park are available for purchase from Archaeology Southwest.