Under the Floors: Archaeology inside the Brown House

The C. O. Brown House in downtown Tucson is now dwarfed by the new concrete-and-steel buildings that have sprung up on either side of it in recent years. But how long, exactly, has this tenacious adobe house been hanging on to the middle of its block on Broadway? Homer Thiel takes a look under the floorboards to tell the story.

In 2011, Desert Archaeology conducted excavations beneath the floors of three rooms within the Charles O. Brown House, located at the rear of 40 W. Broadway Boulevard in downtown Tucson. The Ben’s Bells nonprofit was moving into the space and had decided to replace the existing wood floors, which were in poor condition. A previous test excavation by Statistical Research encountered many artifacts on top of a shallow crawlspace and in the dirt below. Our work had two goals: to determine when this portion of the house had been constructed, and to clear cultural resources from the area beneath the floor prior to the placement of a new tile floor.

The exterior of the south side of the Charles O. Brown house. The western two rooms along this side were excavated (currently the street is closed due to nearby construction work).

Previously, people thought these rooms might date to the 1840s. The University of Arizona Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research had analyzed the beams holding up the roof, which revealed that some beams dated to the late 1840s and some to 1879. So was the house built in the late 1840s, with some replacement beams added in 1879? Or were the rooms built in 1879, re-using old beams?

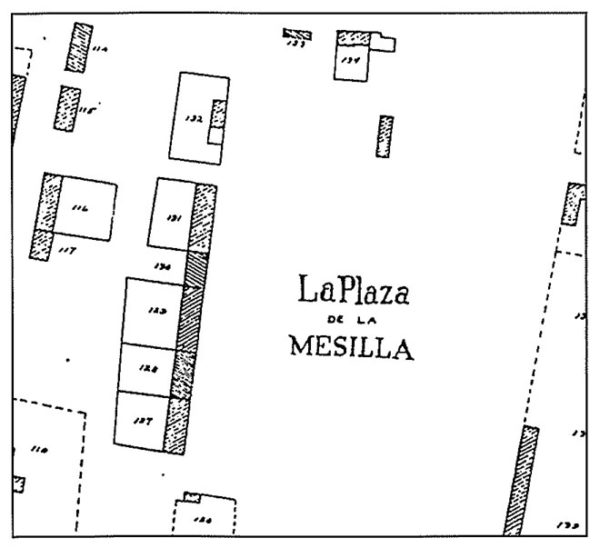

Historical records provided some context. In 1862 the Union Army marched from California to Tucson, pausing for a battle with Confederate forces at Picacho Peak. Once the Union forces occupied Tucson, Major David Fergusson had surveyor John J. Mills draft two maps, one of downtown and one of the fields to the west. Property owners were required to register their land, and U.S. authorities planned to take land from Confederate sympathizers. Two structures were shown on the downtown map in the vicinity of the Brown House.

A portion of the 1862 map of downtown Tucson. The Brown House property is probably lots 130 and 131, located to the left of the plaza.

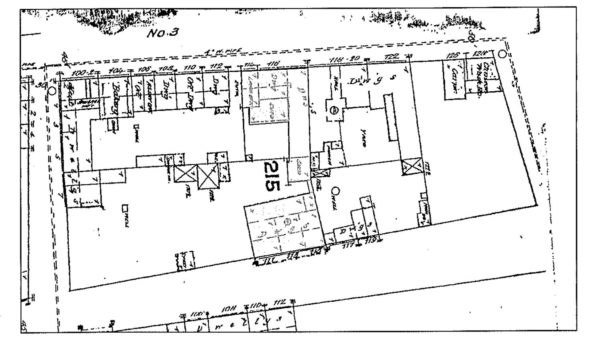

The next detailed map of downtown Tucson was drawn in 1883 by the Sanborn Fire Insurance Company. These exacting maps allowed insurance adjusters in far away offices to determine insurance rates for Tucson buildings. The 1883 map depicts the current configuration of the Brown House.

The 1883 Sanborn Fire Insurance map showing the Brown House in the center, above and below the large 215 (which is the block number). The street at the top is Broadway. We excavated three rooms in the bottom left corner of the house.

Archival research revealed that in 1867 Henry McWard and his wife, Gertrudes Marquez, sold the property where the Brown House now stands to John Capron, who then sold the land to Clara Brown in 1870. Clara was the wife of Charles Owen Brown. His claim to fame was that he owned the Congress Hall saloon, which is how modern Congress Street got its name. The couple had 13 children before separating. Clara died at the house in 1932. By the mid-1920s, the three rooms we excavated were rented out to Mexican-Americans families. After 1936 this portion of the house was used for a variety of businesses. The Brown House survived destruction during the Tucson Urban Renewal Project in the 1960s and 1970s because it had been donated to the Arizona Historical Society.

Our 2011 excavations uncovered the original tamped earthen floors beneath the existing wood floor. Test units against the walls revealed massive rock and mortar foundations holding up the house’s adobe brick walls. Few buildings from the Mexican period (1821-1856) had stone foundations, and no artifacts from this period were found. Therefore, we concluded that this portion of the house was probably built in 1879 and that the older beams in the rooms were likely reused from an earlier house, with no traces left of that building.

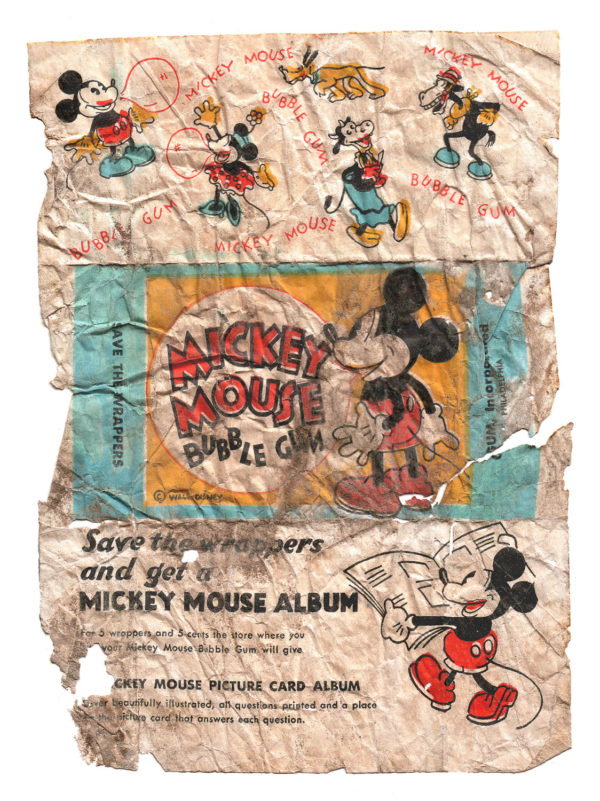

We found a large amount of perishable materials beneath the wooden floors, materials that almost never preserves at open-air sites. While the coins we found dated between 1909 and 1932, the paper artifacts mainly dated to between 1930 and 1937, with most from 1936-1937. It seems likely that many of these items were discarded when the original wooden floors were replaced at that time.

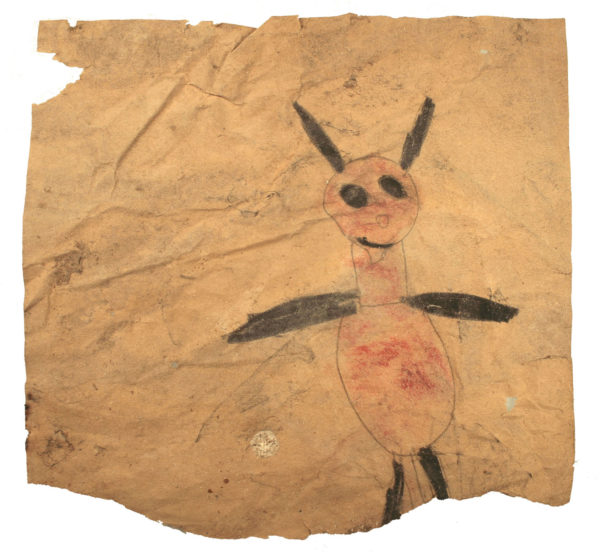

What can the artifacts found tell us about the Mexican-American residents of these rooms? Many items were from children. We found that they played with glass marbles, read newspaper comics and a Disney Big-Little book, and did homework in both English and Spanish.

A Mickey Mouse Bubble Gum wrapper. Children were encouraged to collect wrappers they could trade in (with a nickel) for a Mickey Mouse picture album (photo by Rob Ciaccio).

One adult male living at the house worked for the Arizona Daily Star, and had brought home cardboard printing plates with comic strips on them. Some adults smoked Chesterfield cigarettes and played a card game called malilla.

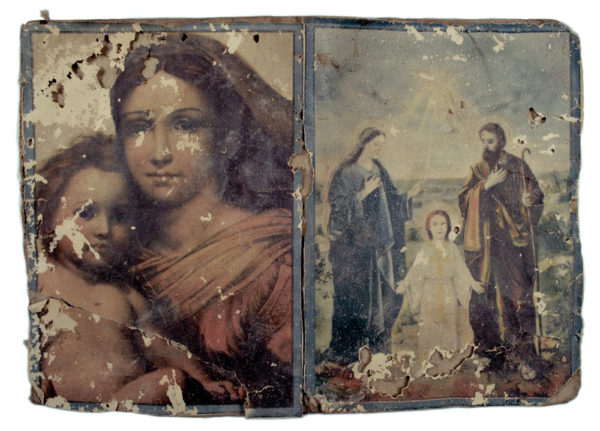

Others decorated their room with prints depicting Catholic saints and probably used a milagro shaped like an arm in prayers that a health problem could be cured. Fragments of lined paper with musical notation suggests someone was playing an instrument. Needles, thread spools, and buttons reveal that clothing was being sewn and repaired.

A religious print, with Maria and Jesus on the left and Maria, Jesus, and José on the right (photo by Rob Ciaccio).

City directories list Mrs. Blanca Garcia, Mrs. M. L. Levy, and Mrs. Refugio Corral as residents of this portion of the house in 1935. The many fragile paper and cardboard artifacts we found beneath the floors of the three rooms provide a glimpse of their lives.

Resources

This project was funded by Ben’s Bells.

The report for the work is available online as a free PDF.