Two Unusual Burials from the Court Street Cemetery

On October 15, 2018, Homer Thiel will be giving a talk at the monthly meeting of the Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society, titled “A Drear Bleak, Desolate Place: The Archaeology of the Court Street Cemetery.” The talk is open to the public and free; find details at the end of this post.

Note: this post contains descriptions and depictions of a child’s burial.

Early October 2018 saw heavy rainfall in Tucson. Eleven years ago, similar storms caused a small sink hole to open in the dirt sidewalk area in front of a house on N. Perry Avenue, near Speedway Boulevard and Stone Avenue. The homeowner looked into the hole and spotted diamond-shaped brass items and some bones. He showed the bones to his wife, a pediatrician, who confirmed what he had suspected: the bones were from a child.

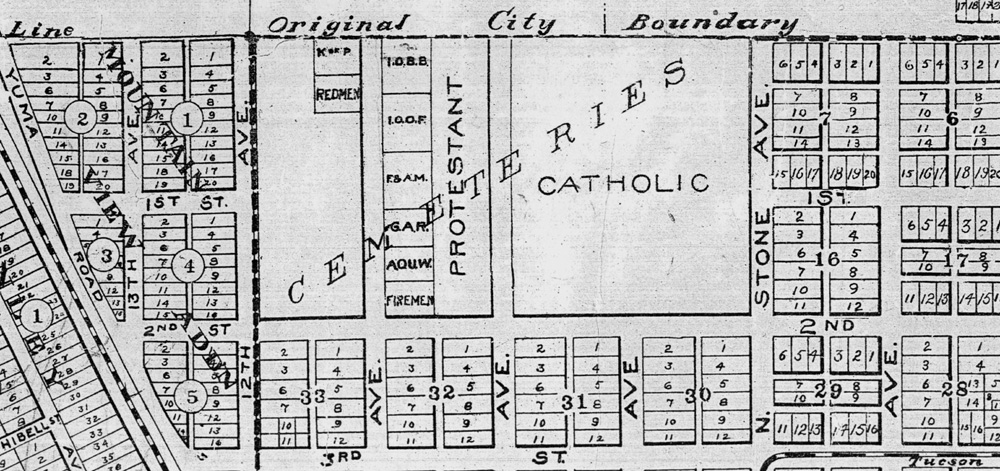

The couple owned a home built on top of the Catholic plot within the Court Street Cemetery. The cemetery was in use from 1875 to 1909, and after calls for relatives and friends to move the approximately 8,000 burials to the new cemeteries on N. Oracle Road, the area was developed in 1916 with homes and businesses. House lots within the Catholic plot may overlie 90 to 100 graves, most likely still containing all or some of the skeletal remains of the people buried in them.

I had met the homeowner earlier in May 2007, when he came to the grand opening of the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson Museum. He told me about finding some embalming fluid bottles while digging a tree hole for a neighbor. I visited him and saw that he had found CHAMPION CONCENTRATED EMBALMING FLUID bottles, manufactured in Springfield, Ohio, along with soda and alcoholic beverage bottles, in an area across the street from the southern Court Street Cemetery boundaries. Apparently a funeral parlor had been discarding their refuse in a hole or wash there.

After finding the grave, the homeowner contacted me, and I in turn contacted the City of Tucson. The City determined that the burial was located in their right-of-way, and the Arizona State Museum granted an Emergency Burial Discovery Case, allowing for the removal of the burial.

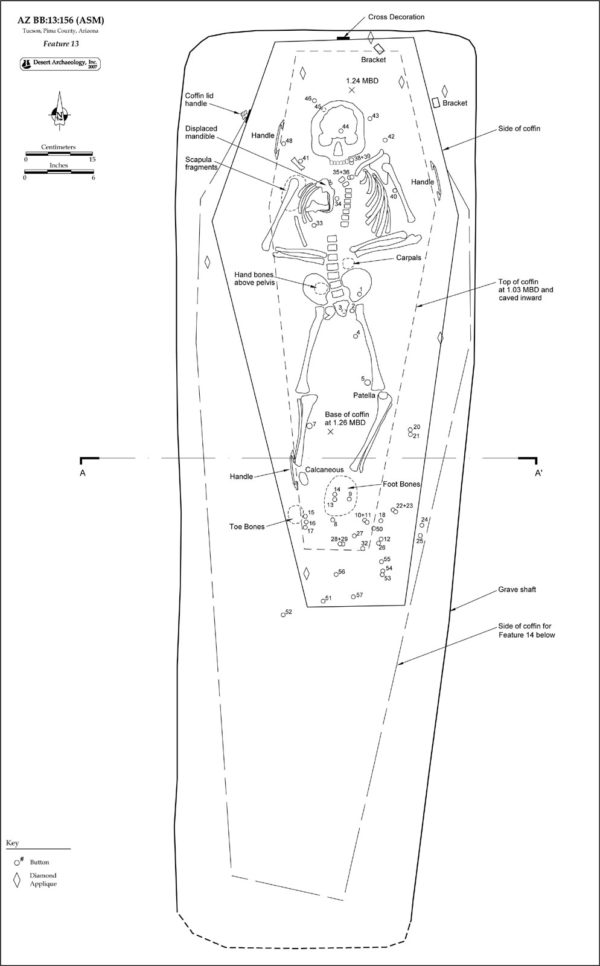

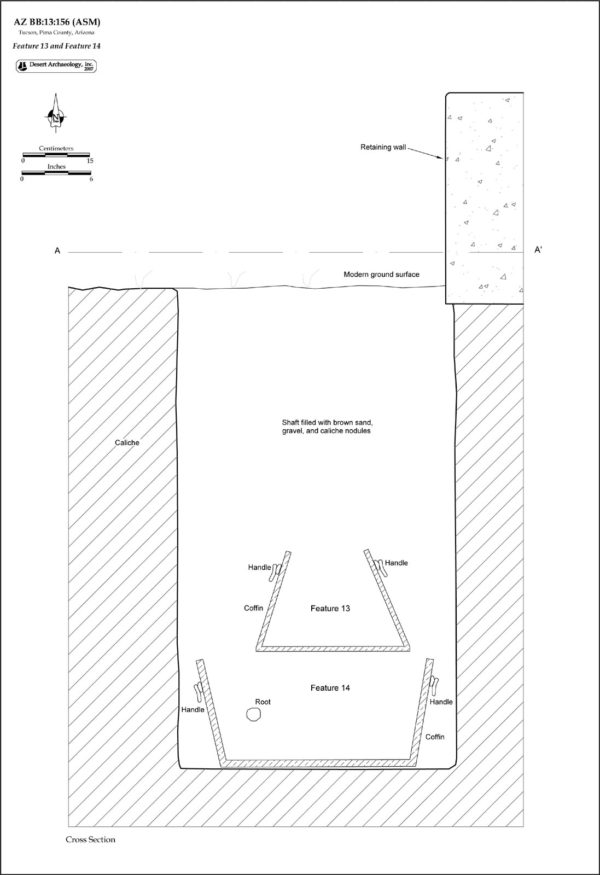

Fellow Desert Archaeology staff member Susan Hall and I excavated the grave, designated Feature 13. We discovered that the burial shaft had cut through the caliche layer, the hard calcium carbonate layer that underlies much of Tucson. Within the grave we found the wooden outline of a mitered-shouldered hexagonal coffin. It was four feet, two inches long and was made from imported Douglas fir. Diamond-shaped appliques were attached to the coffin exterior. A brass decoration, a cross with a seated lamb at its base, had been attached to the head end of the coffin.

Inside the coffin was the skeleton of a child, lying with its head at the north end of the coffin. The child’s arms lay across its lower chest, the hand bones lying on the pelvis.

Michael Margolis (of Tierra Right of Way Services) analyzed the skeletal remains. The child was between two and four years old when it died. Children lack the puberty-related skeletal changes that allow their sex to be identified. Slight shoveling of the maxillary incisors, the upper front teeth, indicate it had Hispanic ancestry. No pathologies were apparent and no cause of death could be determined from the skeleton.

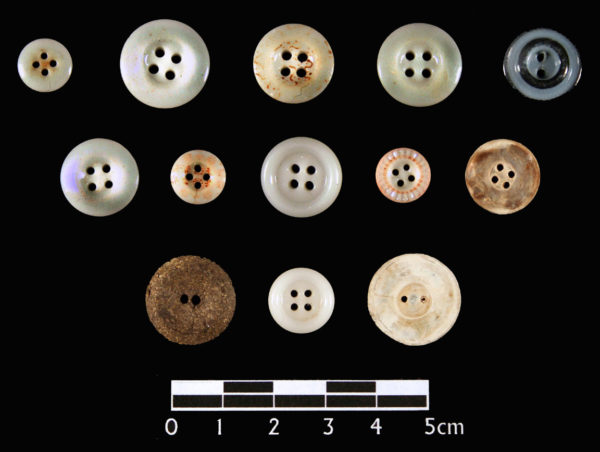

The child was buried wearing a dress with nine small milk glass buttons running down its back and three larger buttons at the bottom of the garment. Both girls and boys wore dresses during the late 1800s, so this could not be used to determine the sex. Another garment had been used as a pillow beneath the head.

At the foot end of the coffin lay over two dozen buttons, apparently from as many as four different pieces of clothing.

This was very unusual—why would there be so many pieces of clothing stuffed into a coffin? The most likely explanation is that the child had died from some very infectious disease, and this was an attempt to dispose of contaminated garments. A number of dangerous diseases affected Tucson residents in the time the cemetery was open, including smallpox, tuberculosis, gastroenteritis (which caused diarrhea), bronchitis, meningitis, cholera, colic, diphtheria, dysentery, malaria, measles, pneumonia, scarlet fever, and typhoid fever. Many of these diseases have been eradicated today, due to better hygiene and waste disposal, along with vaccinations. Others can be cured with an antibiotic shot. Unfortunately, for Territorial-era residents of Tucson, a simple case of diarrhea could prove fatal.

After removing the skeleton, clothing remnants, and coffin, I was puzzled because the caliche continued downward along the sides of the shaft, but there was no caliche directly underneath the coffin. I scraped some soil away and suddenly the forehead of another skull appeared!

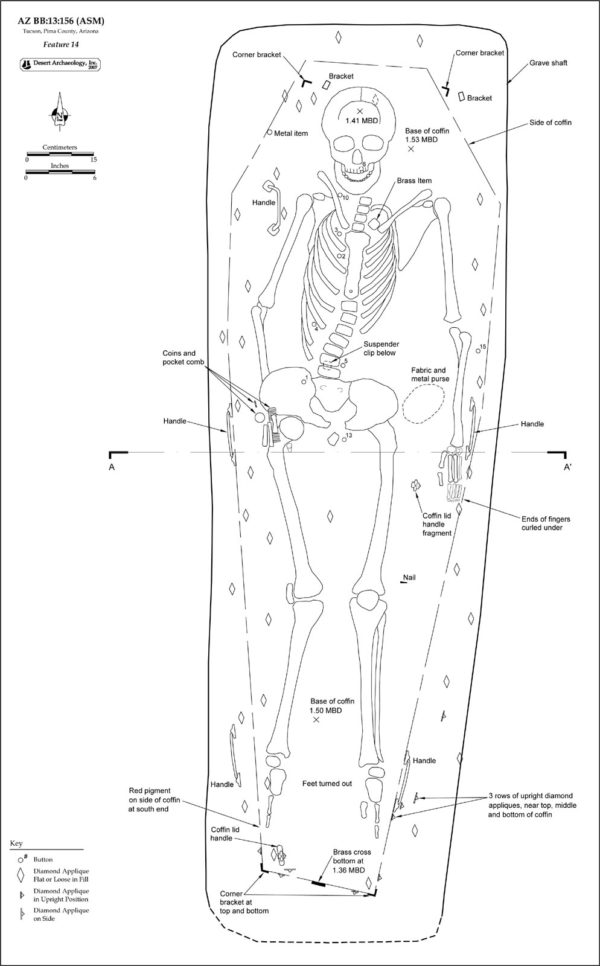

Double burials had been reported before within the cemetery and this was another example. When we returned to excavate this burial(Feature 14) we discovered a much larger coffin, six feet long. It was decorated with identical hardware as the child’s coffin, suggesting that the two had been purchased at the same time from an undertaker. The coffin was made from Douglas fir, had three rows of diamond studs on its exterior, and was apparently painted red on its interior. Five handles were on the outside. A sixth had broken off while the coffin was being handled and was tossed into the grave shaft before the coffin was lowered. A poorly preserved pressed brass cross or crucifix was attached to the foot end of the coffin.

Two coffin handles and a thumbscrew and escutcheon, used to screw the coffin lid down, from the man’s coffin. Photo by Rob Ciaccio.

The individual was an Hispanic male aged between 30 and 35 years old when he died. He was between 5 feet, 3 inches and 5 feet, five inches tall. His teeth had no caries but did have enamel hypoplasia lines, evidence for nutritional stress during childhood. There was mild arthritis in his hands, feet, knees, and elbows. An unusual discovery was that the man had an extra 13th thoracic vertebra with the accompanying extra ribs (people normally have 12 thoracic vertebrae and 12 sets of ribs). This condition would not have affected the man during his life, and he probably never knew that he had these extra bones.

The man was buried wearing a brown woolen jacket, a shirt with milk glass buttons, suspenders, and a pair of pants. He was not wearing shoes.

Another unusual aspect of this burial was the presence of personal possessions that had been in his pants pockets when he was buried. In his right pocket was a hard rubber comb marked L. R. COMB CO. GOODYEAR 1851 and three coins, an 1888 seated Liberty dime, a heavily worn 1877 seated Liberty quarter, and a shield nickel minted between 1867 and 1883. In his left pocket was a fabric coin purse with a brass clasp. Inside was an unidentifiable iron tube and a iron jackknife with its handle inlaid with mother of pearl.

People in the late 19th and early 20th century were very rarely buried with personal possessions. The obvious explanation is that the man had also died from a communicable disease and was buried in the garments in which he had died, without the people preparing the body for burial checking his pockets.

After removing the two burials we noticed that caliche was not present on the south side of the graves. A pin flag we inserted into the wall slid all the way in—about 18 inches—without hitting caliche. This suggests that additional burials are likely present, but because a large tree was growing on top of that area, it was decided to not excavate further. The homeowner has since constructed a small altar to commemorate the discovery.

In the spring of 2018, the two individuals, along with the other burials found in the Catholic portion of the Court Street Cemetery, were reburied in Holy Hope Cemetery.

The project was funded by the City of Tucson.

Resources

Homer Thiel will speak about these burials at the October 15, 2018 meeting of the Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society. Details here.

Learn about the Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society and find out how to become a member here.

A PDF of the report is available on the City of Tucson’s Historic Preservation website.