Setting the Presidio Table: Spanish Dining Ware in Early Historic Era Tucson

Historical archaeologist Homer Thiel discusses dining and serving dishes used between 1694 and 1821 by the Spaniards living in the Presidio.

This holiday season most people will put their finest china on the table, dishes reserved for special use, some handed down through the years and valued as family heirlooms. A previous blog entry described the foods and cooking methods used by the people who lived in the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson. But how were these foods and beverages served?

During the Spanish period in the Tucson Basin, from 1694 to 1821, soldiers and civilians used imported majolica dishes on their tables. Majolica is a type of wheel-thrown, hand-painted, tin-glazed pottery that was originally developed in Spain during the years the Moors occupied the Iberian Peninsula. The Moors were Muslim, and at that time their religion forbade the depiction of human and animal figures on various media, including ceramics. The Spanish artists decorating majolica dishes used floral and geometric motifs and Arabic sayings from the Koran. Some of the these artists were brought to the New World, and majolica production began in the Mexico City region. Pack animals and freight wagons brought boxes of carefully packed majolica dishes over 1,000 miles north to the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson, the construction of which began in 1776.

Initially, blue on white patterns were preferred and are most commonly found in the earliest Presidio features. These vessels resembled high status Chinese porcelains and also contemporary Dutch and French ceramics. Casta paintings from Mexico, created to illustrate racial categories, often included kitchen scenes with majolica dishes displayed on racks.

After about 1800, polychrome vessels, with bright yellow, gold, brown, and green designs were favored. The most common vessel types found in Tucson are bowls and plates with high rims. This makes sense because stews and soups were commonly served. Smaller numbers of cup fragments are found.

We had a display of artifacts at an open house during our excavations at the Presidio. One polychrome sherd caught the attention of a man from Saudi Arabia. He said the design on the sherd was the Arabic word ALLAH. I thought that seemed far-fetched, so sent a photo of the sherd to other people from Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Oman, and Tunisia, asking them if the design on the sherd was a word, but not telling them what the man had said. All responded that it was ALLAH. It is possible that the pattern used on the plate had been transferred to Mexico, and that the plate decorators did not know it was Arabic. Or perhaps it was only a coincidence. I recently showed the sherd to two Turkish visitors to the Presidio San Agustín Museum, where the piece is on display, and they also agreed that it was the word ALLAH.

Compare the design on this polychrome majolica sherd from the Presidio, left (photo by Homer Thiel), with the Arabic word ALLAH, right.

A smaller number of Chinese porcelain vessels were also brought to Tucson, likely used by the higher ranking officers and their wives at the fort. These were blue on white or polychrome cups made in factories in China, shipped overseas to the Philippines, carried by Spanish galleons to the west coast of Mexico, and then carried north via horses or mules to Tucson. These fragile vessels were likely very expensive.

For the women of the Presidio, it was important to use Spanish-style vessels as a way of maintaining their cultural identity. Few, if any, Native American vessels were used as dining vessels on Presidio tables, although large serving bowls were used. The one exception were O’odham-made chocolatero pots, which replaced copper versions that were difficult and expensive to acquire for the soldiers and civilians living in Tucson.

After years of battles, Mexico achieved independence from Spain in 1821. It was previously been illegal for people in Mexico to conduct trade with Great Britain. After independence, Mexico and Great Britain became trading partners in 1824, and British ceramics began to be imported into Tucson in small numbers.

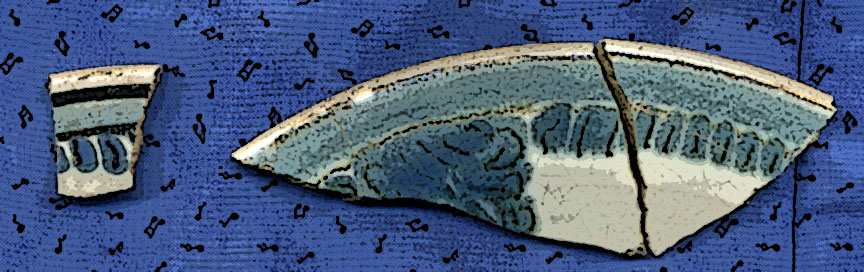

Feather- or shell-edged ceramics have been found. These white pearlware or whiteware vessels were produced in molds with decorative designs along their rims. These designs were then highlighted in blue or green. The style was already starting to go out of fashion by the 1820s, so only a few of these vessels made it to Tucson.

Shell- or feather-edged sherds found during the 1998-1999 excavations in the lawn on the west side of Tucson City Hall (photo by Homer Thiel).

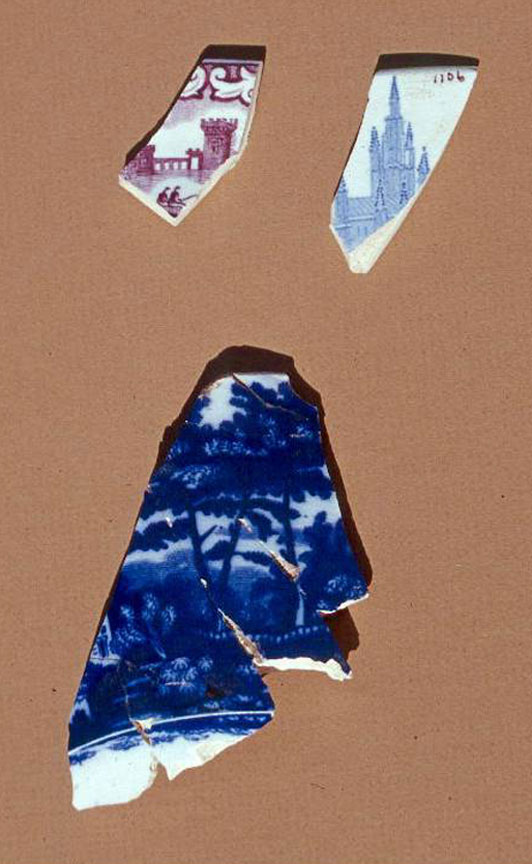

More common are transfer-printed vessels, produced in the Staffordshire area of England. Ceramicists there etched metal plates with scenes from illustrated books and prints, also including border designs with smaller scenes, flowers, and geometric designs. Pigment was applied to the plates and a piece of thin paper pressed on. This paper was then placed on the unfired vessel, transferring the pattern. Blue was the favored color, but by the 1820s other colors—black, brown, green, red, and purple—started to be used.

The transfer-printed ceramics we found during our excavations of the León household in Tucson, dating to the 1840s and 1850s, have scenes of buildings, men fishing, and forests. The people in Tucson had little contact with the outside world, and likely had no idea what contemporary architecture or clothing fashions looked like elsewhere. The images on these vessels provided a glimpse of life far away from the little town of Tucson.

The vessels used by the Presidio residents held symbolic value for them. They linked residents to their families and traditions in Mexico, they provided a way to show higher status, they were a connection to faraway worlds, and they provided the first views of the greater world outside Tucson, just before the community was rapidly changed due to the arrival of Anglos in 1855.

Funding for the research projects these ceramics were found during came from the City of Tucson and Arizona Humanities.