The Soldiers of the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson

Homer Thiel explores what documents and artifacts tell us about the the lives of the Spanish and Mexican soldiers who were garrisoned at the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson between 1775 and 1856.

On August 20th, 1775, Hugo O’Conor, an Irishman employed by the Spanish military, selected the location of a new fortress on the terrace overlooking the Santa Cruz River. Soon, soldiers marched north from the Tubac Presidio to begin construction of the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson. Who were these men? What duties did they have? What kind of weapons did they have? Documents and archaeological finds provide answers.

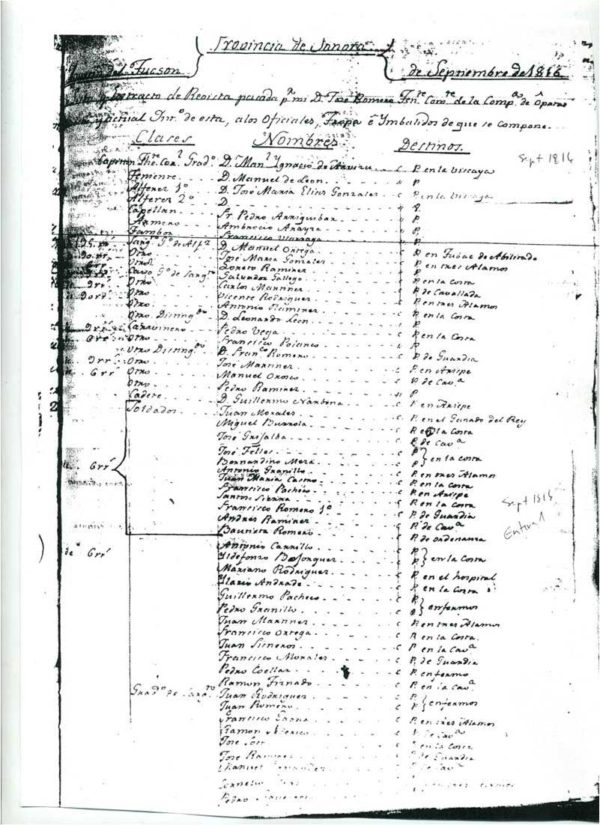

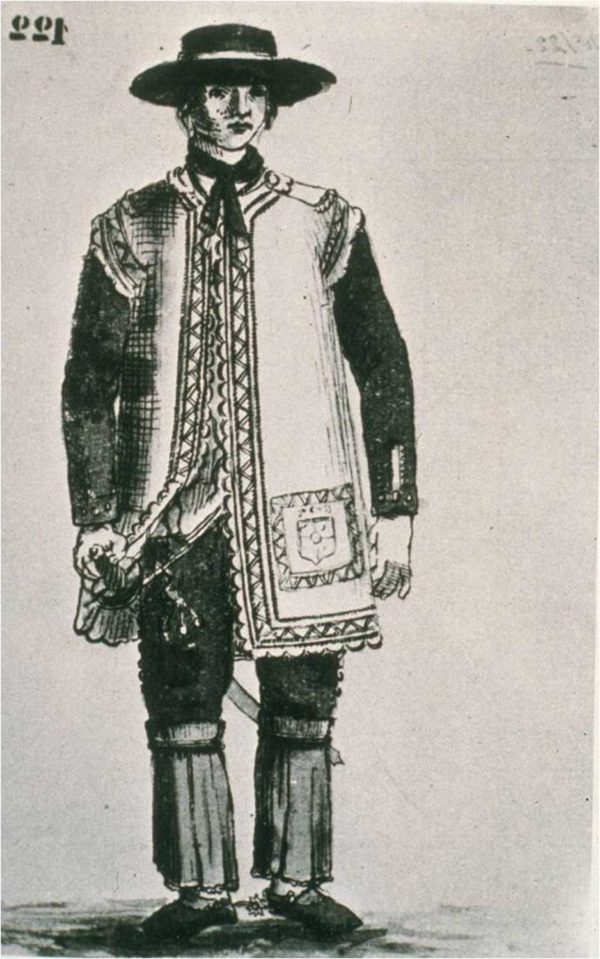

A contemporary drawing of a Spanish soldier. He is wearing a multi-layered cuera, a leather vest that served as protection from Native American arrows.

The documents, found in archives in Mexico and Spain, include monthly rosters. These list all of the soldiers, their ranks, and what their duties were. Soldiers acted as guards at the Presidio, patrolled the region, guarded the cattle and horse herds, and were sent to serve in other places. Soldiers were often sick and sometimes ended up in the post hospital. The rosters also include the enlistment records for new recruits and notes on soldiers being discharged or transferred to other forts, deserting, or dying.

Enlistment records provide biographical data and physical descriptions. As an example, Francisco Diaz enlisted on August 2, 1816 for the standard 10 years. He was the son of Juan Antonio Diaz and Guadalupe Martinez, and had been born in Tucson in 1796 or 1797. He was 5 feet, 1 inch tall, had black curly hair, black eyebrows, brown eyes, a dented nose, and dark skin. Like all of the other soldiers, he was Roman Catholic. He signed the document with an X since he could not read or write. Initially, the soldiers at Tucson came from other places, but as time passed the sons of soldiers enlisted, and by the 1810s, almost all new recruits had been born in Tucson or Tubac.

New recruits spent two months training before being assigned soldering tasks. They drilled on the Plaza de las Armas, practicing with steel-tipped lances. Some were given escopetas (muskets) and learned to load, fire, and care for the valuable firearms. As they rose in rank, some of the soldiers likely acquired smaller pistolas (pistols). The soldiers at the fort melted down lead cannonballs to make musket balls. They carried their weapons during patrols outside the fort, frequently battling Apache warriors.

During the period between the 1790s and 1820s, between 100 and 106 soldiers were stationed at the fortress, with another 12 or 13 pensioned, invalid soldiers. Soldiers served for 10 years, after which they could re-enlist. Many did so because it was the only way they could receive a monthly salary, necessary to buy things like chocolate, cloth, alcohol, and majolica dishes. As soldiers retired, many stayed on in the community with their families, working as farmers in fields on the Santa Cruz River floodplain.

The Presidio was staffed by Spanish and Mexican soldiers for 80 years. One might think that they left ample evidence for their presence, but archaeological excavations within the fort have found relatively few Spanish-era firearm parts. These include a fragment of a ramrod holder, a piece of a trigger guard, and a butt plate that once covered the end of a flintlock musket. As firearms broke, they were taken to the blacksmith shop, where the parts were recycled for use in other firearms or the metal re-used for other purposes.

A butt plate and a fragment of a trigger guard from the recent 2019 excavations at the Historic Pima County Courthouse for the January 8th Memorial (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

The Presidio was built long before the invention of cartridge ammunition, so the muskets and pistols used here fired lead balls with a flintlock mechanism. Desert Archaeology’s Michael Diehl has examined many of these and reports that they come in two sizes, larger ones for muskets and smaller ones for pistols.

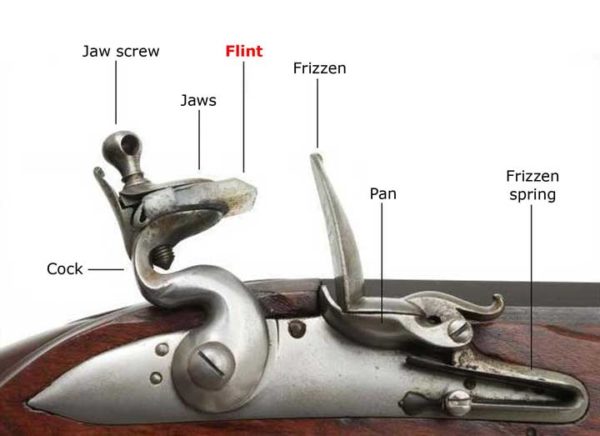

Pulling the trigger on a flintlock musket or pistol started a complicated but split-second mechanical and chemical process, snapping a piece of flint held in steel jaws down across a second piece of spring-loaded steel (the frizzen) that was positioned over a tiny pan filled with gunpowder. This created a spark that fell onto the powder as the frizzen snapped shut over the pan, and the resulting explosion in this confined area propelled the ball out of the barrel toward its target.

The flintlock mechanism (frizzen shown closed over the pan; it would have been pushed forward into an open position before firing).

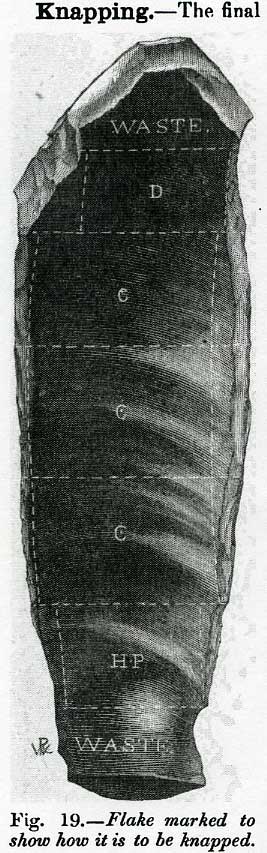

The gunflint at the heart of this mechanism had to be carefully shaped to ensure that it would both fit securely in the jaws and strike the frizzen at the proper angle to create a spark. Each time the flint struck the frizzen, tiny chips would break from its edge, shortening the flint and changing the shape of the edge. The flint needed to be adjusted frequently to compensate for this damage, and eventually would be too worn away to reach the frizzen. A soldier could expect a gunflint to provide perhaps a dozen shots before it needed to be replaced. Armies needed hundreds of thousands of these flints, and they needed to be manufactured to strict specifications to function in the mechanism: rectangular, flat, an inch and a half long, an inch wide, a quarter of an inch thick. To maximize efficiency, the European flintknappers that supplied the various continental armies made long, parallel-edged blades they could quickly snap into several individual flints.

France controlled the gunflint industry in Europe for most of the 18th century, using a distinctive honey-colored chalcedony. The Spanish Crown bought them by the millions to supply their soldiers, including the Presidio garrison. We have found several of these gunflints in our excavations, and have also found numerous honey-colored strike-a-lights. After the flints were too worn down to be used in the flintlocks, soldiers saved them to use for lighting fires, as friction matches were not invented until after 1825.

Gunflint (left) and gunflint recycled as a strike-a-light (right), both made in France, from the Presidio San Agustín (photo by RJ Sliva).

In 2004, Center for Desert Archaeology (now Archaeology Southwest) researchers traveled to communities in eastern Arizona and western New Mexico, seeking Spanish-era artifacts to examine. In New Mexico, a man brought in a Spanish escopeta, which he said had been found by a ranch hand in a crack in a cliff face in the 1940s. The musket was perfectly preserved, its wooden stock covered with elaborate brass decorations and stained from handling. A gunflint was still held in place by a piece of leather.

Many of the Presidio’s soldiers were sent south into Mexico to fight insurgents battling for independence from Spain. Mexico achieved independence In 1821. The soldiers in Tucson immediately switched their allegiance from Spain to Mexico. For the Mexican government, the loss of Spanish financial support meant reduced support for the Tucson Presidio.

Another problem was that Spain refused to sell weapons to Mexico. As a result, the Mexican government turned to Spain’s frequent enemy, England, which had recently wrested control of the gunflint market from France, to obtain firearms. These included muzzle-loading, smoothbore flintlock Brown Bess muskets. Historians had always thought that these were used by the Presidio soldiers. In 1999, Desert Archaeology excavated the home of Francisco Solano Leon, who served in the Presidio from the 1840s and 1850s. A Brown Bess trigger guard was found at the site, verifying that English firearms had been used by the Mexican soldiers. A few years later a second one was found in a well at the Leopoldo Carrillo house near the San Agustín Mission.

Southern Arizona was part of the Gadsden Purchase of 1853, when the Mexican government sold the area to the United States. For several years the soldiers in the Tucson Presidio remained on duty, but finally, in March 1856, they packed up their cannons and their record books, and marched south to Imuris, Sonora. Some of the soldiers, including Francisco Solano Leon, would later return to Tucson, and their descendants can be found here today. Today, visitors to the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson Museum can watch soldier re-enactors march and use their firearms during Living History days.

Soldier re-enactors at the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson Museum in downtown Tucson. The uniforms in the 1700s would not have been this clean.

Resources

Check the Presidio Museum events page to plan a Living History visit

A detailed account of the 19th century gunflint manufacturing industry in Brandon, England