We Have Been Here Before: A History of Epidemics in Southern Arizona

Historical archaeologist Homer Thiel provided information for a newspaper article on the 1918 Spanish flu, published by the Arizona Daily Star on April 6, 2020. This blog entry is an expanded presentation of Homer’s research on the history of epidemics in the Tucson area.

The appearance of the COVID-19 virus (coronavirus) has raised awareness of the dangers of contagious diseases. At Desert Archaeology, we are busy wiping down surfaces, washing our hands, working at home, staying far apart, and taking whatever additional precautions we can to minimize our risk.

Epidemics of communicable diseases have a long history in southern Arizona. We don’t know if they occurred before Europeans came here. But once the Spanish arrived in what is now Mexico, Old World diseases spread northward and dramatically affected Native American communities. Spanish-era Mission records reveal that numerous epidemics took place between 1723 and 1826, killing hundreds of people. Most of these epidemics were measles and smallpox, but one in 1743 included symptoms of “yellow vomit, urine retention, and swollen throat.” At this time, Native Americans had no acquired immunity to these introduced diseases. More detailed information on these epidemics can be found on the Mission 2000 database.

Census records for Tucson survive for 1797 (395 residents), 1831 (431 residents), and 1848 (509 residents). The population appears to have been fairly stable, with about 100 to 110 soldiers, their family members and servants, and retired soldiers and their families. We have no accounts of the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson being affected by an epidemic until 1851, when a disease suddenly killed 122 people, a quarter of the population. The kind of disease was not recorded, but it likely was smallpox. This may have been why authorities decided to create a new cemetery outside of the fortress, a short distance to the northeast. This cemetery was excavated by Statistical Research back in 2007-2008.

Tucson became part of the United States as a result of the Gadsden Purchase of 1853. The Mexican military left in March 1856, and soon a flood of new arrivals appeared on the streets of Tucson. Occasionally they brought communicable diseases with them.

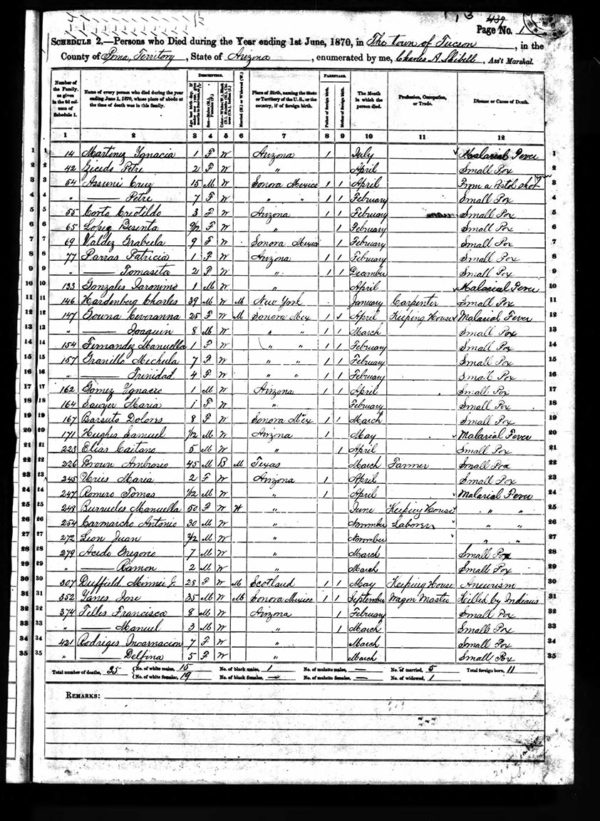

The federal government collected information on deaths in households in the year preceding the decennial census between 1860 and 1880. The forms for Arizona survive for 1870 and 1880. The 1870 mortality schedule lists 139 deaths in Tucson. These included people “killed by Indians,” delirium tremens, and “suicide pistol shot in head.” But most people died from communicable diseases.

The most common was smallpox, which was listed as the cause of death for 78 persons. This was likely an undercount, since deaths listed in other contemporary sources indicate that many were not recorded on the census. The majority of the smallpox deaths occurred among children. One exception was Hampton Brown, a 45-year-old African-American man who arrived in Arizona in 1856 after escaping from slavery in Texas. Arizona newspapers largely kept quiet about the smallpox epidemic, the editors likely aware that it might scare potential residents away from the Territory.

Malarial fever is listed as the cause of death for another 10 people. This disease arrived in Tucson carried in the blood of cattle. Mosquitoes bit the cattle, and then bit people, transmitting the disease. It affected many persons residing in Tucson, and was one of the reasons Camp Lowell, a United States military camp, moved away from downtown Tucson to a spot farther east in 1873.

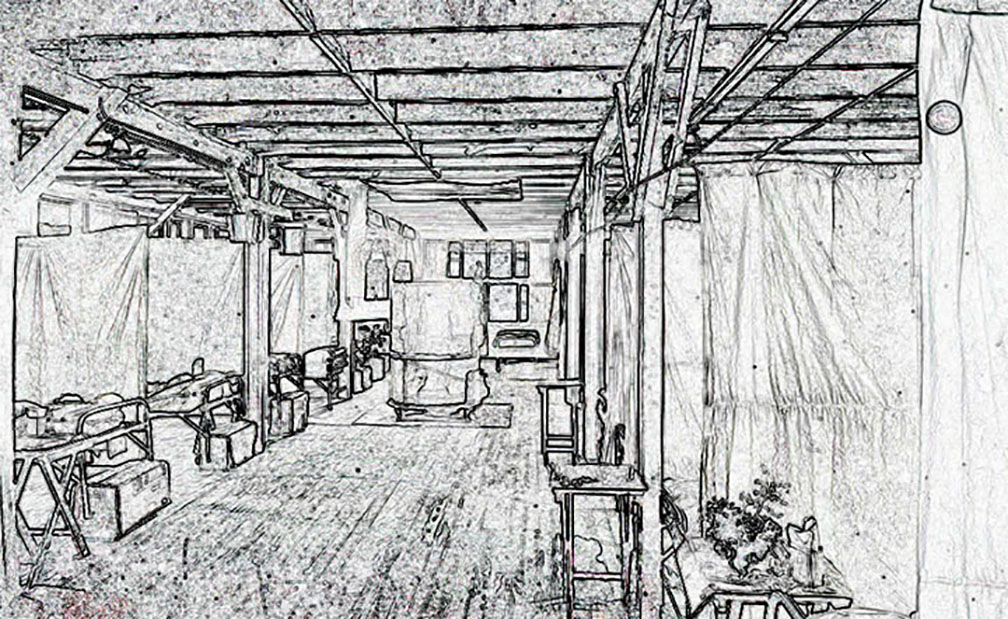

The continued fear of smallpox led to the City of Tucson’s Board of Health, headed by Mayor Tully, to select a four-room house, located a mile south of city limits, as a “Pest House.” People thought to have the disease were quarantined in the house. The Southern Pacific Railroad was required to examine incoming passengers for evidence of smallpox, and a wagon was purchased to transport sick people to the Pest House. Sulphuric acid and chloride of lime were used as disinfectants. Local residents raised money to purchase clothing and bedding for residents.

Eventually, as housing was constructed closer to the Pest House, people demanded that the house be moved to a more distant location. A new brick building was constructed on a property north of St. Mary’s Hospital in early 1906. It had bars in its windows to prevent patients from escaping. At times tents were added to the facility to house excess quarantined patients, and a cemetery was established (the cemetery was moved in the 1960s before a road widening project).

Another communicable disease was tuberculosis, also called consumption or phthisis. As early as 1858, Samuel Hughes moved to Arizona hoping that the dry climate would cure the consumption that afflicted him. He was successful. This was not the case for thousands of other people. Tuberculosis was the leading cause of death in the community from the 1880s to the 1920s. People frequently purchased bottles of “patent” medicines, concoctions that contained alcohol, cocaine, chloroform, and other harmful ingredients.

Dr. King’s New Discovery for Consumption was advertised as “the only sure cure for consumption.” Tuberculosis sufferers who took it were actually ingesting morphine and chloroform.

Scientists identified bacteria as the cause of tuberculosis in the 1890s. The bacteria could be spread through bodily fluids and coughing. In 1898, the Tucson Common Council banned spitting in public in an attempt to halt the spread of the disease.

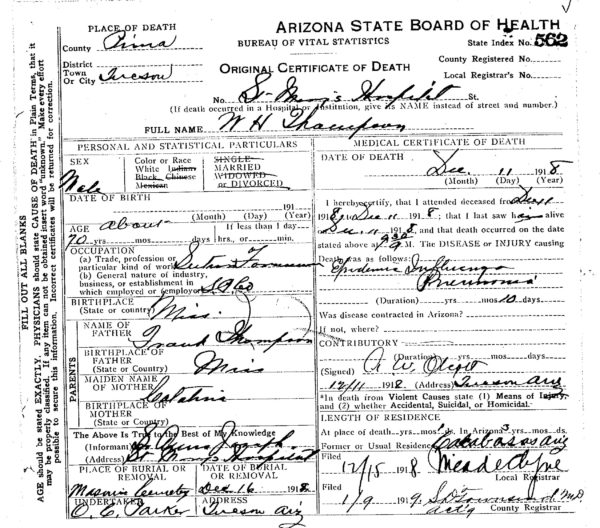

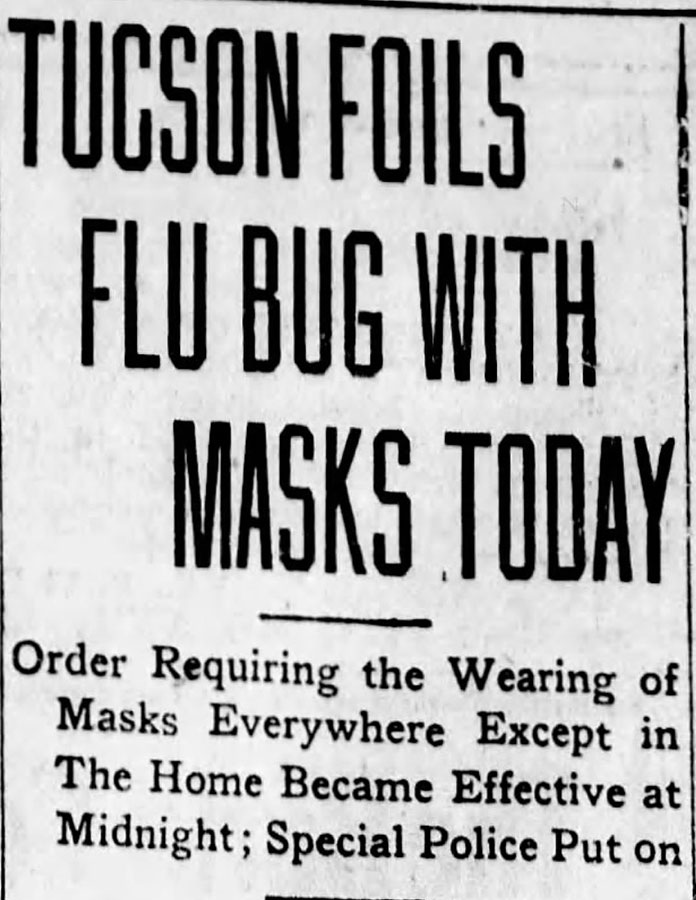

In 1918, a new pandemic spread throughout the world. It was called the Spanish Influenza because the Spanish government was the first to publicize it. Soldiers returning from Europe during World War I helped spread the disease. People in Tucson could read about this in local newspapers, but likely did not expect it to affect the community. They were wrong. The first deaths took place in September. In Tucson, quarantines were quickly established, public gatherings banned, and schools and churches closed. The Arizona Daily Star provided helpful instructions, such as not sharing toothbrushes and keeping away from crowded places. At the same time, the newspaper printed stories downplaying the severity of the disease in the community. Despite this, late in November, everyone in Tucson was required to wear masks in public, with the police charging those who violated the order.

As the influenza epidemic spread, efforts were made to quell it (Arizona Daily Star, 23 November 1918, p. 3).

Despite these efforts, many people were infected. Death certificates reveal that 41 persons died from influenza, pneumonia, and bronchitis in October 1918 in Pima County. In November it was 91, in December 65, and in January 41. The epidemic lasted until April of 1919, with a few people dying later from the lingering effects of the illness.

In all, at least 306 people died, representing one percent of the population of the county. This count does not include tuberculosis sufferers, whose deaths were being hastened by influenza. Other deaths were not reported, including those on Tohono O’odham lands. The death certificates indicate that Tucson and Ajo saw the most deaths. By mid-November, every physician in Ajo was reported to be sick and 25 persons had died there. For the entire county, slightly more males (n=159) died from the Spanish influenza than females (n=144). The hardest-hit age groups were children under the age of 10 and young adults aged between 20 and 29.

As our nation faces the current pandemic, many of the lessons learned from past ones have come into focus. Social isolation, wearing masks, and the brave actions of caretaking nurses and doctors were all factors in the past and continue in the present.

Resources

Information collected for this blog entry was supplied to the Arizona Daily Star, and an article appeared in that newspaper on April 6, 2020.

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 put an end to unproven snake-oil medicines such as Dr. King’s New Discovery for Consumption.