Amazing Maize

Homer Thiel discusses the history of maize cultivation in the Tucson Basin. Desert Archaeology’s work has been instrumental in documenting some of the earliest agriculture in what is now the United States, as well as tracing the ways different peoples have grown and used the grain through time here.

In 2015, the City of Tucson became the first UNESCO City of Gastronomy in the United States, honored for its 4,000 years of food history. An important part of this food history is maize, commonly called corn (a linguistic holdover from England, where all grain crops are referred to as corn). Maize has its origins in southern Mexico, where thousands of years ago people began to plant and tend a wild grass called teosinte. Gradually certain characteristics, including a larger cob with more kernels, were selected for. At first maize supplemented gathered wild plants, but as the number of people living in settlements increased, it became more important. Today maize is the most important grain crop in the world, followed by wheat and rice.

Early Agricultural period agriculture

We collect many soil samples during our archaeological work at Early Agricultural period (2100 BC-AD 50) sites in the Tucson Basin. We process the soil in a flotation machine, collecting the charcoal that floats to the top. After it is dried, ethnobotanist Dr. Michael Diehl examines the samples and identifies the plant remains. Maize survives as cob fragments, charred cupules (the part of the cob holding the kernels), kernels, and pieces of stalks. For prehistoric sites, Diehl identifies pieces of maize that are suitable for radiocarbon dating. The project director will then select samples based on project research questions or to date certain features.

A partial San Pedro phase maize cob found at the Las Capas site.

In the last 25 years radiocarbon-dated samples have revealed that by 4,100 years ago, ancestral Native American farmers were growing maize in field plots along the Santa Cruz River. Relatively few sites from the earliest part of the Early Agricultural period (the Silverbell Interval, 2100-1200 BC) have been studied, but each investigated so far has small quantities of maize. However, wild plants are much more common in flotation samples from this time. How reliant these people were on maize is something that will likely be studied in the future, as new sites or portions of existing sites are examined.

Maize gradually became more important through time, and the size of cobs increased, including how many kernels were in the rows on the cob. During the San Pedro phase (1200 to 800 BC), farmers living in the Santa Cruz River floodplain constructed large field systems and diverted water from the river into canals. The canals then carried water to small field plots surrounded by raised earthen berms. The farmers opened the berm, filling the plot with water, and then closed the berm up again once the plot was flooded. Plots at Las Capas were preserved so well that individual planting holes could sometimes be discerned.

At the Sunset Road site, explored by SWCA in 2015-2016, a late San Pedro to early Cienega phase field system was uncovered, dating between 2,530 and 2,740 years ago. The fields were inundated at some point during that time by a flood from Rillito Creek, which dumped fine sand over the area, preserving the underlying ground. When archaeologists cleared the sand deposits away, they saw ancient footprints that had been left by a group consisting of at least six adults, several children, and a dog. Trackways revealed an adult walking with a child through a muddy field, lifting up and then setting the child down. A dog followed them. In amongst the footprints were the planting pits for the maize crop. SWCA built a viewing ramp and over several weekends thousands of people came to view the discovery. Casts were made of some of the footprints and are curated at the Tohono O’odham Nation Cultural Center & Museum in Topawa, southwest of Tucson.

One of the fields uncovered at the Sunset Dairy site. Visible are the small canals and berms surrounding the field plot (photo by Homer Thiel).

One of the footprints encountered at the Sunset Dairy site (photo by Homer Thiel).

Storing the crop

In the Sonoran Desert, maize was planted in the months of May and June and would typically be harvested in the months of September and October. Some maize was likely eaten fresh, either roasted on the cob or cut off and cooked in stews and soups. Other ears of maize were left to dry on the stalk or perhaps while hanging in strands on the interior or exterior of pit structures and ramadas.

Some of the maize was then prepared for storage, both for next year’s seeds and also for later consumption. The maize kernels were stripped from the cob by hand and then placed in containers. Baskets and leather bags were likely used during the Early Agricultural Period. These may have been placed in underground storage pits for short periods of time, but long-term storage in pits is unlikely to have been used because dampness could cause the maize to sprout or mold.

During the Early Ceramic period (AD 50-500) and Hohokam era (AD 500-1425), people stored maize in ceramic jars. The openings in the jars could be covered with lids made from large sherds and sealed with clay, preventing damage to the contents by rodents, insects, and water. Two granaries, marked by circles of small post holes on pit house floors, have been found in the Tucson Basin. The posts supported platforms that kept the storage jars off the floor.

A pit structure at AZ AA:12:46 (ASM), near the Pima Animal Care Center, had a granary on its east side (photo by Henry Wallace and Robert Ciaccio).

Most maize storage vessels were probably placed on house floors or in internal pits. During the excavations at the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson Museum site in downtown Tucson, we encountered a Hohokam pit structure with an enormous internal floor pit. The house had burned. Many clumps of charred kernels were found on the floor and nearby outside the house, suggesting the residents had pulled the burned maize out of the pit in an attempt to salvage some of their crop.

Historic period maize

O’odham farmers were growing maize, beans, squashes, and watermelons when the first European missionaries and soldiers visited the Tucson Basin in the 1690s. Watermelons are an African crop, meaning the seeds arrived in the area—transported from villages already contacted by Europeans—before the Spaniards themselves came to the banks of the Santa Cruz.

Father Eusebio Kino, a Jesuit priest, distributed the seeds for Old World crops. Among these was wheat, which soon became a favorite among the O’odham and the Pima to the north because it ripened at a different time than maize, thus providing a food source during a time of the year previously known for food shortages.

The Spanish soldiers and their families who lived at the Tucson Presidio preferred wheat over maize, since maize was viewed as a Native American food. Still, they grew both and incorporated maize into their diet. An 1804 report by Jose de Zúñiga, the Presidio commander, reveals that the residents of Tucson had raised 2,800 bushels of wheat and 600 bushels of corn in the preceding year. Among the dishes the Presidio residents prepared was pozole. An ingredient in pozole is hominy, which is corn soaked in lye to remove the outer kernel coating. This process, called nixtamalization, made maize more digestible. Other maize dishes included tortillas and tamales.

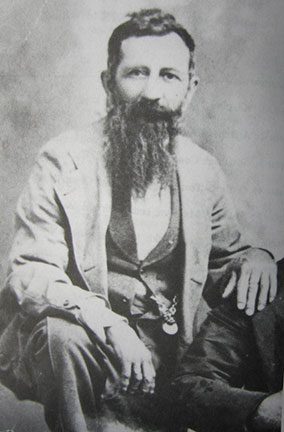

George Hand arrived in Tucson as a Union soldier during the Civil War. He is known today for his diaries, which chronicle his life from the 1860s to 1880s. He recorded that he and other soldiers stole green corn several times in September and October 1862. He wrote “Corn is good for soldiers. The Mexicans watch it very close but we get the best of them very often.” He later would return to Tucson and operated a saloon before becoming the janitor for the Pima County Courthouse.

George O. Hand, diarist, Civil War soldier, saloon keeper, and janitor (1830-1887).

Tamales are made from masa, a dough made from nixtamalized corn flour, which is pressed around meat, cheese, or vegetables and then wrapped in a dried corn husk and steamed. In Territorial-era Tucson, tamales were steamed and kept warm in Tohono O’odham ollas set over a fire and watched over by Mexican and O’odham women, who sold tamales on the streets. The Arizona Citizen reported on October 25, 1873, that a man dropped a shell cartridge in one fire. It exploded, causing the olla to break and scaring the cook. He was promptly arrested and fined $35. In 1882, chicken tamales and fresh oysters were available daily at the San Francisco Restaurant at 14 Mesilla Street.

Tamales steaming in a tamalera (Wikipedia commons).

Today tamales can be purchased at supermarkets, street vendors, or restaurants in Tucson. You can try a variety of tamales at El Charro, a Tucson restaurant established in 1922 by the Flores family and located near the Presidio. It is the nation’s oldest Mexican restaurant run continuously by the same family, following the tradition of 4,000 years of cooking with maize in the heart of Tucson.