What’s for Supper? Exploring Historic Period Diet in Tucson

In December 2015, Tucson was designated a UNESCO City of Gastronomy, the first in the United States. This honor was given for many reasons, among them Tucson’s 4,100 years of agriculture, the interest in preserving heritage crops by Native Seed Search and the Kino Heritage Fruit Tree project, and the cross-border food traditions available in local restaurants.

We’ve explored the prehistoric Tucson Basin’s ancient foodways in previous blog posts. But what did people eat here during the more recent past? Five data sources help us examine the historic period diet of people who lived in Tucson during the Spanish (1690s-1821), Mexican (1821-1856), and American Territorial (1856-1912) periods.

Documents

Documentary sources can include government records, diaries, letters, store ledgers, drawings, and photographs. We know that there were extensive herds of cattle and sheep at the Spanish-era Presidio San Agustín del Tucson fortress because they are mentioned in reports and soldiers were listed as guarding the king’s cattle herd on monthly rosters.

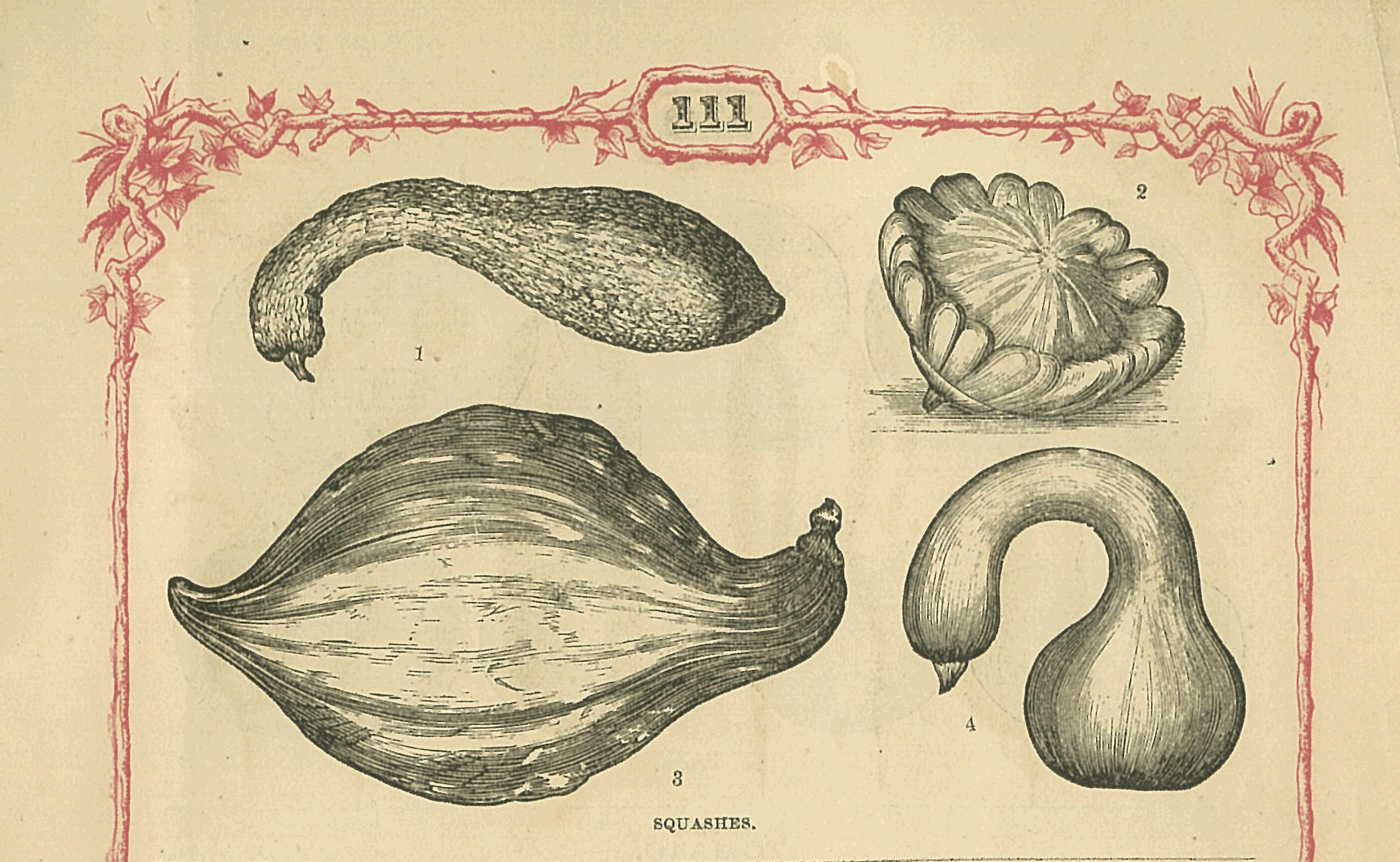

Beginning in 1846, with the passage of the Mormon Battalion through Tucson, we have written accounts describing foods available in the community. On September 24, 1854, James Bell had dinner with the Comandante of the Tucson Presidio. The first course was rice with chili verde in a separate dish, but meant to be eaten together. Then a large dish with piles of separately cooked beef, squash, quinces, whole peppers, and green beans, perhaps resembling modern-day fajitas, since flour tortillas were served with it. The third course was dried beans and peppers. For dessert they had a boiled flour and almond pudding with a peach marmalade sauce. Doubtlessly, the ordinary citizens of the fort had less elaborate suppers.

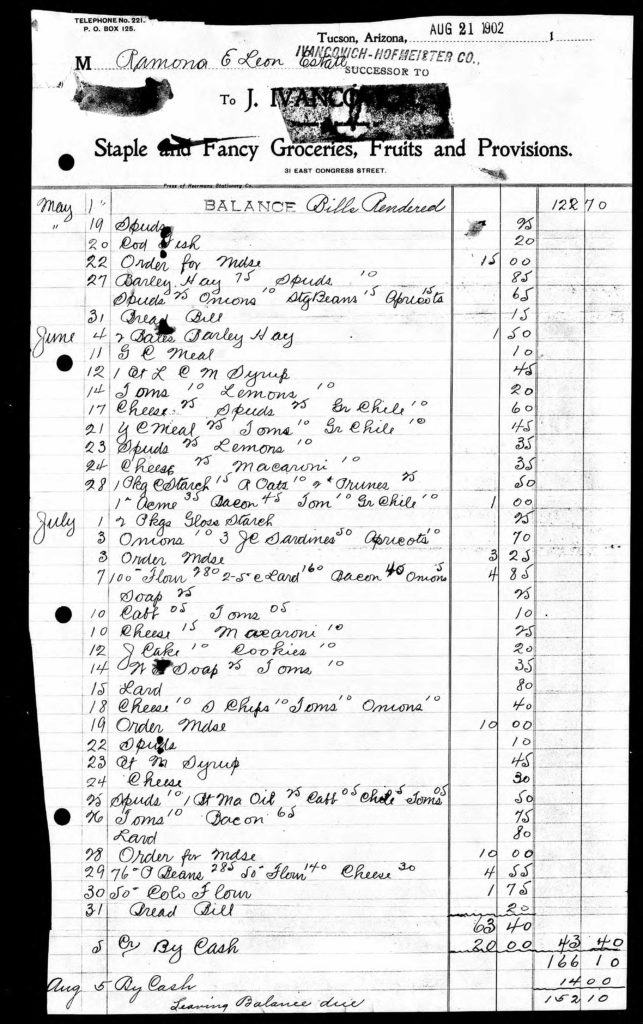

Store ledgers list purchases made by individuals and families. After Ramona Elias de León died in 1902, the Ivancovich grocery store submitted a copy of their store ledger so that the estate could pay for items bought there. Spuds (potatoes), green chilis, apricots, onions, s. chips (Saratoga chips, today called potato chips), and bacon were among the items. The listing for June 24, 1902, reveals that the León family enjoyed a meal of macaroni and cheese.

J. Ivancovich store ledger for Ramona Elias de Leon’s household, 1902 (Pima County Probate File 1367).

Many documents do not survive. When the Mexican military left Tucson in 1856 they took the civil, church, and military archives, and most of the records disappeared. The records that survive often focus on wealthy, powerful people. Luckily, archaeological data can help fill in the blanks.

Food processing and preparation tools

While some fruits and vegetables consumed in Tucson were eaten raw, most foods were processed or cooked in some fashion. During the Presidio era, wheat and maize were ground in donkey-powered rotary mills. The flour was then used to make tortillas that were fried on ceramic comals. Bread was baked in domed adobe brick ovens.

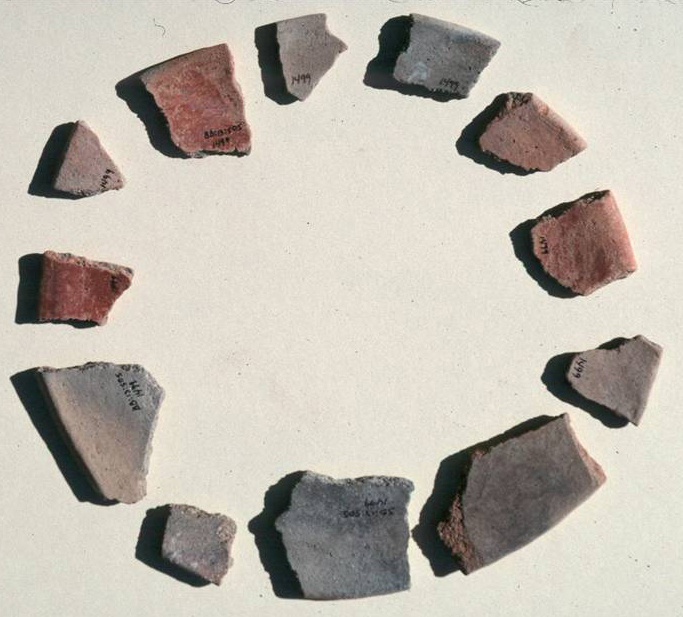

The lack of refrigeration meant meat had to be quickly eaten fresh or preserved in some fashion, such as by drying. The Spanish ate a lot of meat-rich soups and stews, and the people in Tucson used Native American pots to cook them.

A Spanish Period Sobaipuri bean pot, used by the residents of the Tucson Presidio to make soups or stews (photograph by Homer Thiel).

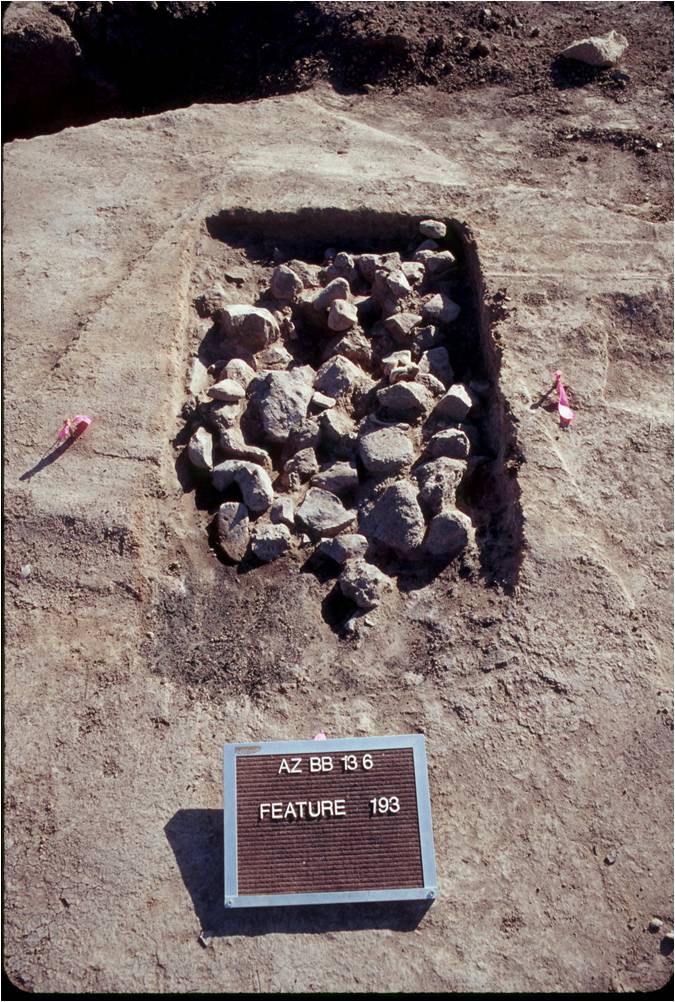

Meat was also cooked in barbeque pits. One was found at the San Agustín Mission, with a layer of charred mesquite branches set onto the pit base. Rocks were piled on top after the fire had burned for a while, and when heated, joints of beef were placed on the rocks. The meat was then covered until it was cooked. We found a few stray bones that had fallen off the meat lying on the rocks when we excavated the pit.

The Territorial period saw cook stoves brought to Tucson. We rarely find evidence for these stoves, as they were sturdy and transportable, and if broken, the thick iron was recycled. We also find few cooking pots or pans, although fragments of ceramic mixing bowls are common. Food service artifacts—pieces of plates, bowls, cups, saucers, pitchers, platters, and silverware—are very common, and even these can tell us something about meals. Territorial restaurants served butter on small ceramic dishes called butter pats, each diner getting a single serving with their meal.

Animal bone and seafood

There were no vegetarians at the Tucson Presidio and probably few during the Territorial period. Tucsonans ate a lot of meat and threw away the bones into trash piles and pits. Desert Archaeology’s faunal analyst, Jennifer Waters, has examined thousands of bones recovered from downtown Tucson. What has she learned?

Chopped cattle and sheep bone recovered from a trash midden at the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson site (photograph by Homer Thiel).

Butchering practices changed over time. During the Spanish and Mexican periods, carcasses were chopped apart using axes and cleavers. The meat was either stripped from the bone or cooked in large bone-in roasts. Bone was further smashed into smaller pieces and boiled to extract the fat (tallow) that could be used for cooking or for greasing things like wagon axles or pulleys. The American Territorial period saw the introduction of saws, which allowed for more precise butchering and the cutting of larger carcass segments into individual cuts of meat. People from the eastern United States preferred to eat fried meats and processed meats, such as cured bacon or sausages, which leave no archaeological trace.

The vast majority of meat eaten in Tucson came from cattle, with smaller quantities of mutton, pork, and chicken. Few wild animals were consumed. During the Presidio era, it was dangerous to go out hunting because of the presence of Apache in the region. During the Territorial period, there were few wild animals in the immediate area around downtown Tucson, although newspaper accounts describe duck hunts in lakes formed by damming the Santa Cruz River. Some wild game was brought downtown and sold to butchers by local Tohono O’odham, but this was not common.

The Chinese men growing produce along the river also raised hogs and carp. Their diet was more diverse than that of other Tucsonans. They ate a wider variety of animals, including domesticated cats and imported dried fish and cuttlefish, a squid-like creature.

Oysters were a luxury food item, often reserved for special occasions such as wedding dinners. Tinned oysters came overland packed in freight wagons. Fresh oysters traveled via stagecoach packed in ice. After the 1880 railroad arrival, seafood (fish and shellfish) was sent to Tucson in barrels of saltwater and was widely available in stores and restaurants.

Plant foods

Father Eusebio Kino visited Tucson in the mid-1690s and found fields of corn, squash, beans, and watermelon. Watermelons are an Old World crop and the seeds arrived in Tucson, passed from village to village northward, long before the first European explorers. Many other Old World plants soon were carried to the community including fruits (peach, apricot, quince, and grapes) and grains (wheat, barley).

A glass bottle that once held Crosse & Blackwell raspberry preserves, recovered from Historic Block 91 (photograph by Robert Ciaccio).

As noted in a previous blog entry by Dr. Michael Diehl, Desert Archaeology field personnel collect bags of soil for flotation. On historic digs we target trash middens and privy fill, two features likely to yield plant materials thrown out as garbage or as human waste. Wheat and corn are commonly found. Wheat was considered a higher-status food than corn, and we find that wealthier Mexican-American households ate more wheat than poorer households. European-American households have more raspberry seeds, likely once found in bottled raspberry jam. Occasionally unburned plant remains are found. At the León Farmstead, a piece from a nutmeg and two coffee beans were recovered, neither of which were mentioned in the ledger document.

Food and beverage containers

In January 1855, Solomon Warner traveled from Yuma to Tucson on a freight wagon packed with goods, including canned goods and bottles of alcoholic beverages. The next 25 years saw countless shipments from Yuma, San Diego, Guaymas, and Santa Fe. The 1880 railroad arrival ended most freighting and allowed vast quantities of foodstuffs to be shipped cheaply from manufacturing centers throughout the world.

A lot of food came in tin cans. Unfortunately, cans preserve poorly in the acidic dirt of southern Arizona. When found by archaeologists, cans are usually broken into small pieces. The loss of paper labels means the contents are almost always unidentifiable, the exception being rectangular meat cans with key openers and large lard buckets.

Glass bottles were used for a variety of foods and beverages. Contents are often identifiable due to the distinctive bottle or jar shape, embossed product or manufacture names, or the rare occasion when a paper label survives. Ceramic containers for marmalade are an unusual find. Analysis of preserved food and beverage containers has shown that upper-class households had a much greater variety (13.5 different products) than lower socio-economic class households (on average 5.2 products).

The future of dietary research

New methods for researching diet are being developed. Residue analysis looks for the chemical signature of foods. Isotopic analysis of animal teeth can show where animals originated from. DNA research will likely provide answers to questions about food and diet we have yet to think up.