New Insights on the Tucson Presidio from the Historic Pima County Courthouse

Homer Thiel discusses ancient and historical cultural resources encountered on the grounds of the Historic Pima County Courthouse in Tucson during renovations and the construction of the January 8 Memorial.

Pima County has recently completed the renovation of the 1929 Pima County Courthouse, now the home of the Southern Arizona Heritage and Visitor Center and the University of Arizona Alfie Norville Gem and Mineral Museum. In addition, the January 8th Memorial has been completed on the west side of the Courthouse. Desert Archaeology conducted excavations at the courthouse prior to these renovations and monitored the construction work, documenting the variety of cultural resources we encountered along the way.

A Hohokam Village

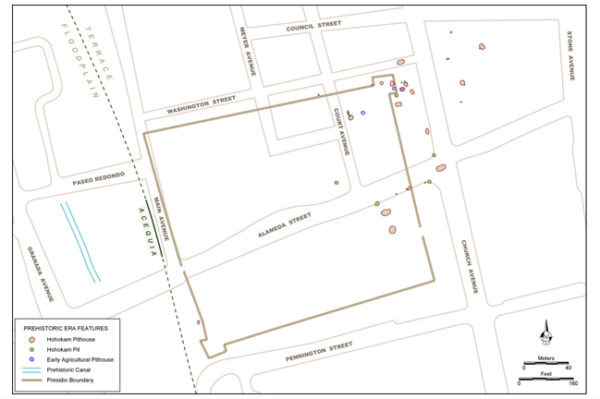

The heart of downtown Tucson is located on the terrace east of the Santa Cruz River floodplain. The terrace slopes downward toward the river, whose waters people used to irrigate agricultural fields. People have been utilizing this area for over 4,000 years. About 2,000 years ago, Early Agricultural period families constructed small, circular pit structures on the terrace (one of which is on display within the Presidio Museum). Later, between AD 750 and 1150, Hohokam people lived in a large, sprawling village built where the courthouse now stands. We encountered three Hohokam pit structures during our construction monitoring, adding to the many documented during other archaeological work here.

Locations of prehistoric features in downtown Tucson (drafted by Catherine Gilman, Desert Archaeology).

It is likely that many other Hohokam houses are present in as-yet unexplored areas. The ancestral Native Americans of this time period often constructed ball courts, where games were played and people interacted, and it is likely that one of these elaborate structures was present somewhere in the downtown area.

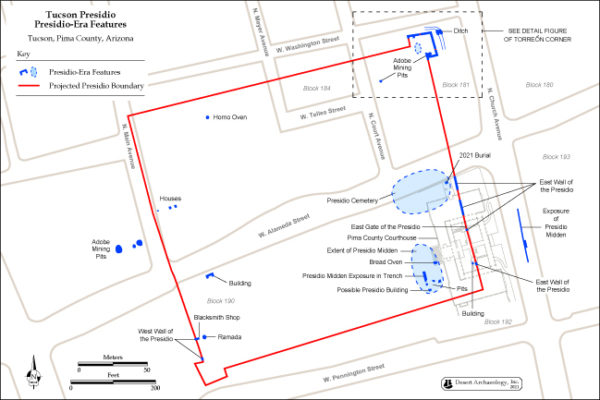

A Spanish Fortress

Construction of the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson, a Spanish fortress, began in 1776. Workers dug up a large amount of dirt, mixed it with water and plant materials, and molded it into sun-dried adobe bricks. The garrison then used the areas where they had mined the soil for trash disposal. Beneath the January 8th Memorial area, we excavated a series of trenches into one of these Presidio-era trash middens in a probable soil mining pit west of the courthouse. We found large quantities of animal bones, plant remains, and artifacts.

Location of Presidio-era features in downtown Tucson (drafted by Catherine Gilman, Desert Archaeology).

Previous excavations in this area most commonly turned up large numbers of beef bones and a few sheep. However, the current work found the opposite, with larger amounts of sheep bones. The explanation for this lies in a thick layer of trash containing many sheep skulls and foot elements—the inedible parts of the carcass—that appears to represent materials discarded after whole animals were roasted for a feast.

But which feast? Plant remains in the midden pointed us to a specific season. We found many pits from peaches, which typically ripen in late July and August, along with common bean, maize, and Arizona walnuts, all of which become available in late summer. During the Presidio era (1776-1856) and extending into the following Territorial period, residents of Tucson celebrated the Feast of Saint Augustine in the late summer. Saint Augustine of Hippo, the patron saint of the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson, died on August 28, 430. The feast in Tucson began on August 28th with a procession to the chapel, where a priest gave a sermon. A festival ground with a tamped earth dance floor was nearby, surrounded by booths where food and drinks were served and gambling games could be played. At night musicians played instruments and people danced. The festival lasted for two weeks.

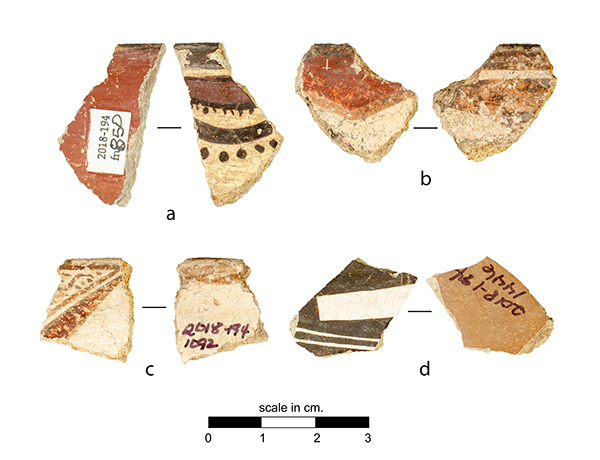

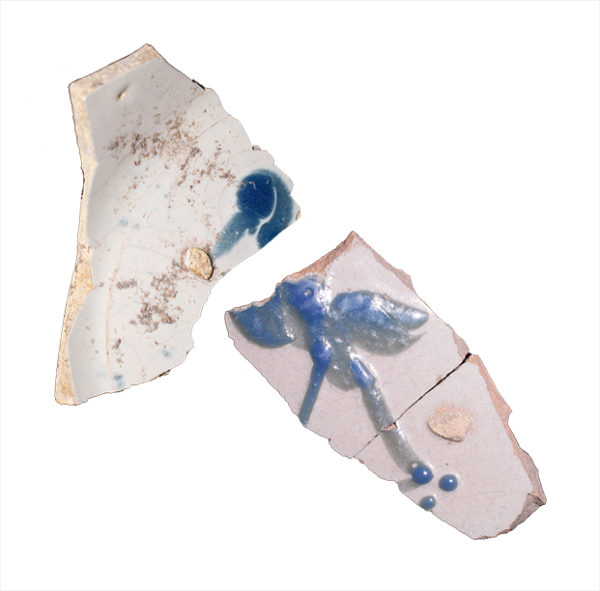

Artifacts found in the midden included pieces of Mexican majolica pottery, expensive Chinese porcelains, and local O’odham cooking and storage vessels. Also found were 26 sherds of Hopi pottery, carried south from the pueblos in northern Arizona. We know that in 1793 the commander of the Presidio led a group of soldiers to visit Zuni, and the soldiers likely brought many small bowls back as souvenirs. At other times, Hopi tribal members traveled south to visit Tucson, one of their ancestral homelands.

A blue-on-white majolica plate with a bird design (Photograph by Robert Ciaccio, Desert Archaeology).

We also found soldier uniform buttons and a British belt buckle. After Mexico became independent from Spain, Mexico entered into trading agreements with Great Britain, with that country selling arms and uniforms to the Mexican government. A rare find was a butt plate and a portion of a trigger guard for an escopeta, a Spanish musket. Most firearm parts were likely taken to the Presidio blacksmith to be repaired or recycled. Previous work had only found a few other firearm parts. Gunflints, the most commonly found parts, originally were imported from France and eventually locally made. As they wore out, they were reused as strike-a-lights, with a piece of iron knocked against them to make a spark to start a fire.

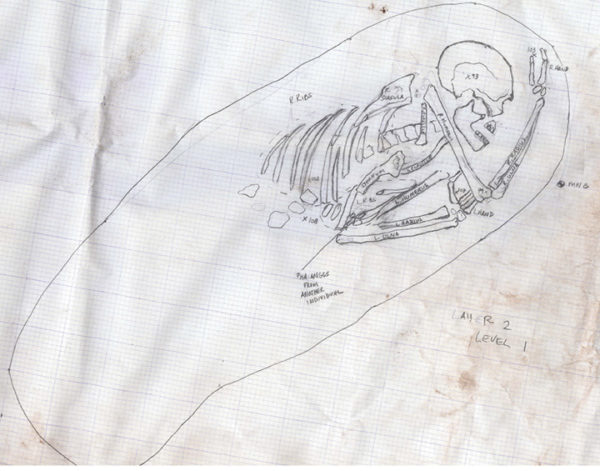

The Presidio chapel and cemetery were located in what is now West Alameda Street and surrounding areas. A water line trench at the west end of the project area encountered the remains of two individuals, which had been disturbed sometime in the past. In July 2021, trenching for a new sidewalk on the north side of the courthouse encountered an intact grave from the cemetery. The individual was lying on their left side, in a fetal position, almost certainly representing someone who died in their sleep and was buried after rigor mortis had set in.

Drawing of the burial of the Presidio soldier (drafted by Erina Gruner and Katie Bubnekovich, Desert Archaeology).

Osteologist Dr. James Watson identified the person as a Hispanic male, aged between 35 and 50 at death, and between 5’2″ and 5’5″ tall. He had arthritis on his right elbow and on the mid-back vertebrae. He also had lost one of his lower molars. The man was probably a Presidio soldier. He was not buried wearing any clothes, as during the Presidio era clothing was very valuable and most people were buried wrapped in a cloth shroud. Remains from three other individuals were encountered in nearby historically disturbed soils. All of these remains will eventually be repatriated to Los Descendientes del Presidio de Tucson for re-interment in their plot in Holy Hope Cemetery. It is likely that hundreds of other Presidio-era individuals still lie beneath West Alameda Street.

Territorial Government Buildings

The United States took control of the Presidio in 1856. Americans rapidly dismantled the walls, constructing stables and homes on the site. In 1868, the first Pima County courthouse was built here. This adobe building had a thick rock foundation. We found a small portion of that foundation. Nearby we found the foundations of the first Tucson City Hall, completed in 1883. The back of the building housed a jail and we found a portion of its collapsed wood plank floor. Beneath the wood planks were rows of upright iron bars, put in place to prevent prisoners from tunneling out of the jail.

The blackened floorboards of the City Jail with upright iron rods barely visible (Photograph by Homer Thiel, Desert Archaeology).

The 1868 courthouse was torn down when a new courthouse was constructed in 1881. This brick, Victorian style building had a dome on top. Inside the building was a large water tank, filled daily, for probably the first flush toilets in Tucson. The large cesspool for the waste was dug into the ground to the west of the courthouse and covered with a wooden roof. In 1889, after the wood decayed and collapsed, a new roof was constructed from long railroad rails that were covered with wood and then soil for a lawn. In 1911 a hole opened in the lawn and the deep cesspool was rediscovered. It was then filled with many loads of dirt.

The 1881 Pima County Courthouse. The yellow area in the lawn on the left side was the location of the cesspool.

Finally, a small sinkhole opened up in the northwest portion of the now Astroturf-covered courthouse courtyard. The hole turned out to be a rock-lined square, one foot to a side, where a well had been drilled for the 1883 Pioneer Hose No. 1 firehouse. This was the first fire station for Tucson and was in use until 1907. At first the hose cart and water tank were pulled by lines of men. Later, horses were purchased to pull the vehicles.

The well shaft was filled with dirt and wood. After documentation, it was refilled with sand. Similarly, the remains of the government buildings and Presidio-era trash middens were covered with a protective fabric and the area refilled, preserving the archaeology in place. The January 8th Memorial was recently completed over the area.