For My Own Use and Benefit: How Hampton Brown Escaped Slavery and Built a Life in Arizona

Homer Thiel uses historical documents and archaeological data to bring together the story of Hampton Brown, a formerly enslaved man who lived in Territorial period Tucson after escaping from Texas. Peter Enneson assisted with the research for this post.

One of the first African-Americans to arrive in Arizona during the American Territorial period was a man named Hampton Brown, who was sometimes known as Ambrosio Brown. He was born about 1824 in Texas. Brown is not listed by name in the 1850 US census for Texas. At that time enslaved people were listed on a separate census schedule under their owner with only their age, sex, and color noted. Brown was almost certainly enslaved by a man named Thomas Decrow, who was listed as owning a 30-year-old Black male slave. This becomes pertinent, because in 1856 Hampton Brown escaped Texas with Mary (Kuykendall) Decrow, Thomas Decrow’s white sister-in-law.

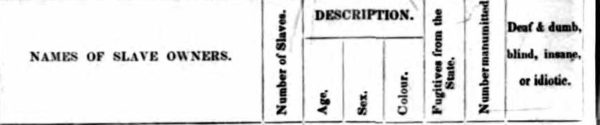

The 1850 Federal census Slave Schedule for Matagordas, Texas lists Thomas Decrow as having one 30-year-old, male, Black slave.

Mary, born in 1818, had been married to Howard Decrow, and had four children with him, two dying in infancy. After Howard’s death, Mary and Hampton fled Texas together, Mary leaving behind her two children and being called deceased in legal documents even though she was alive. At first the couple apparently headed south into Mexico, where many escaped slaves achieved freedom.

The couple soon arrived in Arizona, and by March 1860 the two were working at a pine lumber camp in the Santa Rita Mountains south of Tucson. Camping nearby were Larcena (Pennington) Page, the wife of John Page, and 11-year-old Mercedes Quiroz. Larcena was suffering from malaria and her husband thought the higher elevation would help her recover. He was away from the camp when Apache raiders appeared, kidnapping Larcena and Mercedes. The two dropped bits of cloth torn from their clothing and bent branches as they were marched over the mountains toward the San Pedro River, marking a trail. Eventually, the Apache spotted a search party led by John Page. Larcena was ill and could not move fast enough. When the group reached a ridge, an Apache thrust his lance into her back. She was pushed off the ridge and, after being wounded numerous times with other lances and hit with rocks, left for dead. Three days later she regained consciousness. Over the next two weeks she crawled back across the mountains. Eventually she reached the lumber camp, where Mary Decrow dressed her wounds.

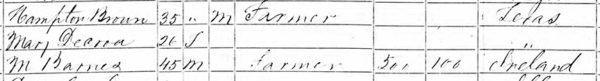

By August 1860, Hampton Brown and Mary Decrow were living on the San Pedro River, where he and M. Barnes worked as farmers.

Hampton’s relationship with Mary ended. By 1862 he had entered into a new relationship with Crisanta Lopez, who had been born about 1847 in Mexico. The couple’s first child, Marianna, was baptized in Tucson in 1863.

The Brown family headed north to Prescott, Arizona. There on the 1864 Territorial census Crisanta was listed as “Mistress of Negro Brown.” Mary Decrow was also living nearby with her future husband, Cornelio Ramos. While in Prescott, Hampton Brown prospected for ore and minerals, eventually making several claims. In June 1865, he sold his mining interests and moved south to the San Pedro River, where he claimed a quarter section of land and began farming. He was also hunting wild game for the United States military and continued prospecting for ore. A son, Manuel, was born around 1865.

Why didn’t Hampton Brown and Crisanta Lopez get married? In December 1865, the Territorial Assembly passed a law making it illegal for Black or mulatto persons to marry white people. At that time Mexican-Americans were considered white. The law would not be repealed until 1962.

In 1866, Brown and Crisanta’s brother Juan Lopez raised 50,000 pounds of corn from their land on the San Pedro River. It is likely that much of it was sold to the United States military, which had numerous camps and forts scattered throughout southern Arizona.

In November 1867, Hampton was in Tucson when he registered his brand: “I have this day adopted for my own use and benefit a branding iron marked [HB joined] for the purpose of branding all animals that may become my lawful property.” He also claimed a town lot in Tucson. The couple had another son, Juan, born around 1867 and a third son, Manuel Maria, born in 1868. Brown sold his land on the San Pedro in July 1869, reserving the corn crop in the ground.

Storekeepers in Tucson maintained ledgers in which they recorded purchases made on credit. Entries for Hampton Brown exist in his probate file and in ledgers archived at the Arizona Historical Society. A list from John Archibald’s store reveals Brown purchased three pairs of pants, four pair of hose, two pairs of socks, two pairs of boots, seven pairs of shoes, a cashmere shawl, and two other shawls. Cloth (calico, cambric, and plaid), and sewing goods- tape, ribbon, hooks and eyes, and thread- indicate that the women in the household were sewing clothes. Other purchases in the period between January and March 1870 included soap, bleach, candles, tea, and harmonicas.

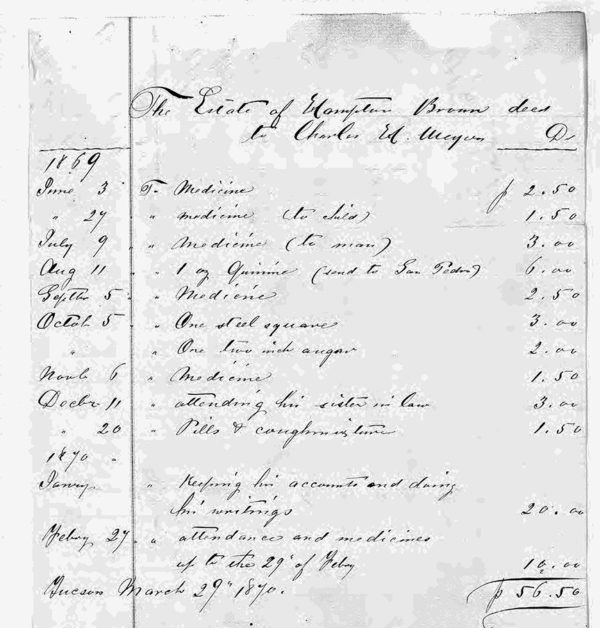

A ledger account from Charles Meyers’ store reveals that Meyers was “keeping his accounts and doing his writings” for Hampton Brown, who could sign his name but was otherwise unable to write.

In early 1870 a smallpox epidemic struck Tucson. In a matter of weeks dozens of people died, mostly young children. But among the victims was Hampton Brown, who died from the disease on March 11. His probate file contains a bill that reveals the family had purchased claret (a Bordeaux wine made in France) and brandy two days before his death, the alcohol perhaps being administered to Brown as he was dying. The claret would have traveled over 5,600 miles to arrive in Tucson, a testament to the reaches of the global economy in the 19th century.

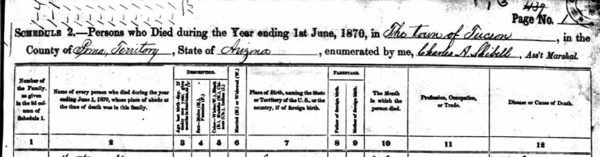

The 1870 census collected mortality data. Brown appears as Ambrosio Brown in the entry recording his death from smallpox.

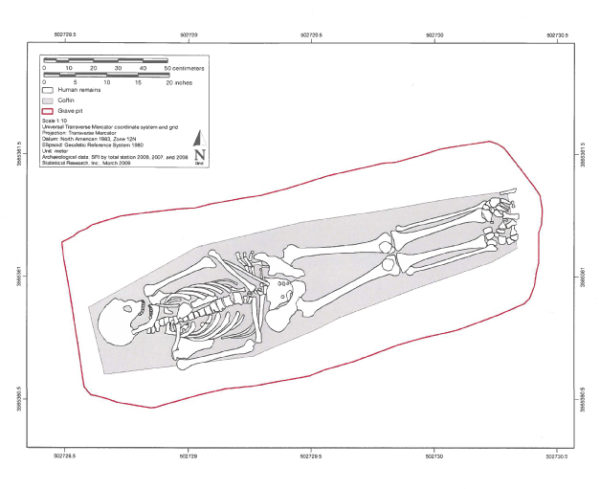

At the time of Hampton’s death, Tucson’s sole cemetery was located at the northeast corner of North Stone Avenue and East Alameda Street. Statistical Research, Inc. discovered most of the cemetery prior to the construction of the Pima County Consolidated Justice Court complex, locating over 1,000 mortuary features. Two of them were identified as African-American males. One of these (Feature 6941), discovered in the area thought to hold Protestant burials, may have held the remains of Hampton Brown. The individual buried in Feature 6941 was an adult male aged between 35 and 45 years at death. He had been placed in a shouldered coffin, his head to the west, his hands crossed over his pelvis. The man had been dressed in a shirt with five white porcelain buttons, pants with three iron buttons, and a coat with two badly corroded brass military buttons. Two badly corroded coins were present, one placed on the forehead and the second lying beneath the skull. There was evidence the man had been wrapped in a cotton canvas shroud. The coins had likely been placed on his eyes, an old custom that was sometimes used to keep the eyes of the deceased shut. Osteologists who examined the man’s remains identified dental caries, tartar deposits, and periodontal disease. They also saw healed fractures of the 1st thoracic vertebra, the fourth right metatarsal, and the lower left humerus. These injuries could have been caused by hard work or accidents.

Plan view drawing of Feature 6941 from the Alameda-Stone Cemetery (courtesy Statistical Research, Inc. and Pima County).

Two years after Hampton died, Crisanta Lopez married William Allen and eventually had four children with him. She died in 1927. Descendants of Hampton Brown live today in California.