What’s in that Bag of Dirt? Flotation Samples and Archaeology

Michael Diehl, Desert Archaeology’s resident paleoethnobotanist, brings us the first installment of an occasional series about the world of flotation samples.

Buy a five-pound bag of flour. Dump out the flour. Grab a spade, head out into your yard, and shovel in enough dirt to fill the bag. Fill your bathtub, pour the contents of the bag into your tub. Swish it around for a while. Scoop up everything that floats using that dip net that came with your fish tank, and dump the stuff onto a paper towel.

Tanya Yatskievych measures the volume of the dirt from a flotation sample using a graduated bucket, and pours the sample into Desert Archaeology’s purpose-built flotation tank.

After it’s dry, grab a magnifying glass. Look at it and you will see insect parts (wings, legs mandibles, heads, thoraces), tiny terrestrial snails, bits of roots, probably small bits of mica, bits of tiny roots from plants, insect and rodent droppings… and seeds.

OK, don’t do that at home. It’s messy and the contents really aren’t pretty by most aesthetics. Just the same, collecting “flotation samples” from archaeological sites, and identifying the seeds and charcoal that float to the top, is part of the ordinary business of understanding what people ate in the past, and why they ate it. Everyone knows that prehistoric people in the American Southwest ate maize, beans and squash. So what more need one know?

Actually, the story is much more complex. And the story of agriculture in the American Southwest is a short one—only four thousand out of the last 12,000 years of human occupation. Unless you’re really into mushy stew, you probably don’t want to just eat corn. You might want flavors—saltiness, sweetness, bitterness, the heat of capsaicin so central to modern Southwestern cuisine; those flavors may come from chilis, pigweed, goosefoot, tansy mustard, or other wild plants. So really, it’s not just about maize, beans, and squash, or how much of those things were eaten. Instead, it’s about how people organized their lives around producing, foraging for, processing, and disposing of food.

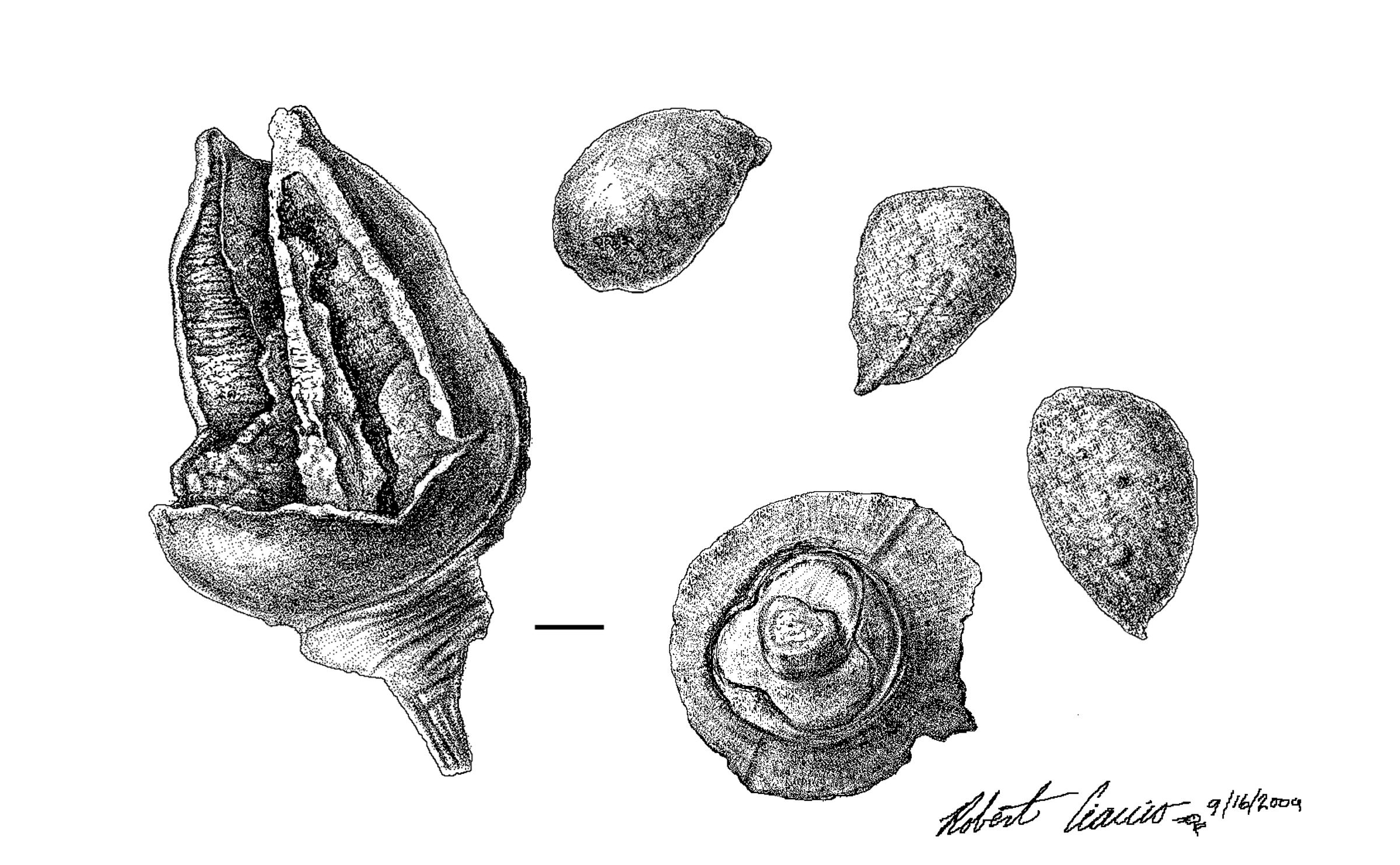

Corn is not always the big story. This sample from northwestern Phoenix contains identifiable wood charcoal. Mesquite pods stand out in this photograph, but under the microscope, other plant tissues will be observed.

Bags of dirt are great for addressing all the strange and wonderful questions surrounding how people went about food provisioning in the past. The answers may even be helpful for future planning, as eminent paleoethnobotanist Paul Minnis has often noted. From time to time, I’ll be checking in with my blog entries. “What’s in that Bag of Dirt?” will take readers on a tour of interesting discoveries, obscure facts, and lesser known plants that I’ve seen in flotation samples over the last three decades.

The Desert Archaeology paleobotany lab. When I’m not writing, I’m looking through a microscope. I’ve been doing this for 27 years, and have examined the contents of something like 8,000 flotation samples from five states, mostly Arizona and New Mexico.

Resources

Find Dr. Diehl’s publications on paleoethnobotany at his Academia.edu page (free site registration required).