The Archaeology of Children in Territorial-era Tucson

Historical archaeologist Homer Thiel is back with more insights into life in 19th century Tucson–this week, about the kids.

What was life like for the children who lived in Tucson during the American Territorial Period, from 1856 to 1912? Surviving documents—newspaper articles, school records, and censuses—can tell us some basic facts about their lives, but archaeological data can provide information that wasn’t written down.

The late 19th century was a time of changing attitudes towards children. They were no longer viewed as miniature adults—little people to be put to work as soon as possible. While children still did chores at home, and some worked to help support their families, most attended school and were allowed time to play.

Education

During the late 1800s, education transformed from being a luxury for rich people to a publicly funded endeavor. The first boys’ school opened in Tucson in 1867, and the Sisters of Saint Joseph opened a girls’ school in 1870. We commonly find education or literacy artifacts at downtown sites. These can include pen nibs, ink bottles, slate pencils, brass pencil ferrules (the part that holds the eraser), chalk, and school slate fragments. By the early 1900s, most children in Tucson were attending public schools and the rate of illiteracy had dropped dramatically.

Toys

Along with a longer period of education, children were often expected to spend time at play. Manufacturers in Europe and the eastern United States began to produce a wide variety of toys marketed toward youngsters. Many of these were educational in nature, helping prepare kids for their future roles in life. Girls were expected to learn domestic skills, including cooking, taking care of homes, and raising babies. Miniature tea sets and doll houses allowed girls to enact their future roles.

Cup, saucer, and tea pot from a child’s tea party set discarded by the Coleman family on Historic Block 91 (photo by Rob Ciaccio).

Dolls played an important role, and the type of dolls found at a site can help determine the social economic status of families. Fragments of four varieties of European porcelain dolls are found in Territorial-era sites in Tucson. The least expensive were Frozen Charlottes, named after a poem about a spoiled girl who refused to wear a coat on a winter sleigh ride and froze to death. These small, solid porcelain dolls have non-moving arms and legs. Children or mothers could sew simple dresses for them.

Seven inexpensive, identical Frozen Charlotte dolls, found discarded on Historic Block 139 in Tucson (photo by Rob Ciaccio).

Next was a hollow version with movable arms and sometimes legs. More costly were hollow-headed dolls with separate arms and legs that could be attached to a cloth or leather body. The most expensive were larger hollow-headed dolls which had applied glass eyes, porcelain teeth, with molded hair or (now missing) human-hair wigs, also once attached to a cloth or leather body.

A blond boy doll head, which once had inset glass eyes and was sewn to a cloth or leather body, found on Historic Block 95 in Tucson (photo by Rob Ciaccio).

Toys manufactured for boys are also common, especially clay and glass marbles. Other boys’ toys found in Tucson include toy guns, lead soldiers, model trains, and toy wagons (by the 1920s, toy automobiles and airplanes appear).

An unglazed and a glazed fired clay marble from Historic Block 181 in Tucson (photo by Rob Ciaccio).

A selection of glass marbles found at the C. O. Brown House, Historic Block 215 in Tucson (photo by Rob Ciaccio).

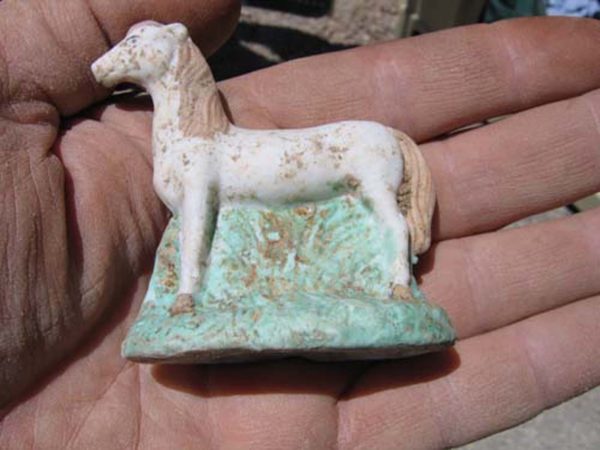

Some toys were played with by both boys and girls, such as the bisque porcelain figurines that are occasionally found at sites in Tucson. To date, we have recovered figurines of a golfer, a “speak-no-evil” monkey, a dog, and a horse. We have also found checker pieces, dominoes, piggy banks, a mechanical bank, and harmonicas.

This painted horse figurine was recovered from a privy pit on Historic Block 83 (photo by Homer Thiel).

The toys we find at open-air sites are almost always made from non-perishable materials- chiefly ceramic, glass, or metal. Perishable materials—cloth, paper, leather, and cardboard—were used for many toys. Desert Archaeology’s work beneath the floors of the historic Charles O. Brown House (40 West Broadway), prior to installation of new floors for the nonprofit Ben’s Bells organization, resulted in the recovery of items made from these materials. Post-dating the Territorial period (the finds mostly dated to the 1930s), they provide an idea of what we don’t find at open-air sites. They included a folded paper boat, a wooden spinning top, two rubber balls, a jump rope handle, an alphabet block, and a miniature basket with tiny eggs, suitable for a doll house.

A miniature basket with tiny eggs was found beneath the floor of the C. O. Brown House, Historic Block 215 in Tucson.

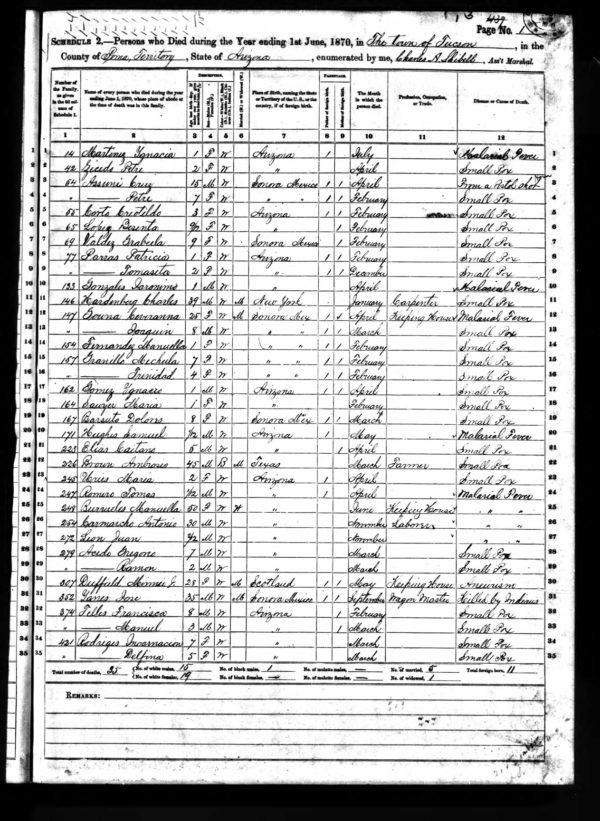

Life and death

Child mortality was high prior to the development of modern medicine. During the Territorial period, perhaps one third to a half of the infants born in Tucson died in childhood. As an example, the 1870 United States Mortality Census reveals that smallpox killed 70 children under the age of 13 in Tucson. Another 17 died from other causes, and these counts reflect only those individuals who reported deaths in their households.

A page from the 1870 United States Mortality Census listing deaths in Tucson. The age at death column is to the right of each person’s name, and the cause of death is on the right side of the page.

Poor nutrition, poor sanitation, and infectious diseases all contributed to the problem. Steps were eventually taken to improve conditions—modern sewer and water systems were developed, parents became better educated about nutrition, and a health officer quarantined families whose members had smallpox, measles, and other dangerous diseases.

For children who did perish, the Victorian era saw increasingly elaborate funerals. Richer families would contact one of the funeral parlors that opened in Tucson (the first by E. J. Smith in 1878) and purchase a coffin, robe, and embalming, and hire a hearse to transport the body to the cemetery. Sometimes photographers were asked to take a picture of the deceased child. Poorer families might make their own coffin and have a mass at the Catholic cathedral.

Work conducted by Statistical Research, Inc., prior to the construction of the Joint Courts complex at Stone and Toole Avenues resulted in the excavation of over 1,000 graves from the Alameda-Stone Cemetery (known historically as the National Cemetery). They found many children buried wearing crowns of artificial flowers, symbolic of their innocence.

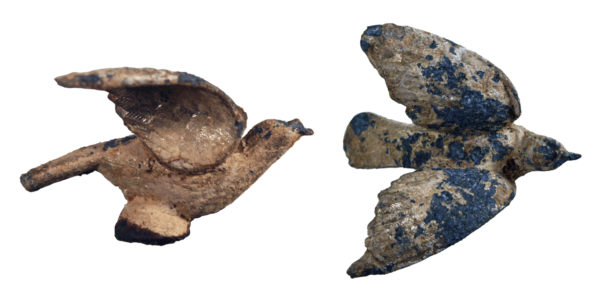

Desert Archaeology has excavated several child burials in the Court Street Cemetery. Children were buried in coffins with special decorations—a lamb seated beneath a cross, doves, or handles bearing the phrase “OUR DARLING.” Two coffins in the International Order of Red Men plot had bouquets and wreaths of roses placed on their lids. Clearly, although common, the death of a child was still a traumatic experience for parents.

A dove caplifter, once attached to the lid of a child’s coffin, found in the Pima Lodge 10, International Order of Red Men plot within the Court Street Cemetery (photo by Rob Ciaccio).

Excavating children’s things can be a curious experience for the archaeologist. Hundred-year-old broken toys can bring back memories of our own childhoods, for many of us the days prior to computer games, when toys taught you things and might also have been a little dangerous (remember lawn darts?). Coffin decorations make you think about the perilous nature of childhood back before a quick vaccination or a antibiotic shot could prevent illness or save a child from death. Regardless of the nostalgia or sentimentality they might spur, these finds play an important role in filling out our understanding of daily life in Territorial-era Tucson, particularly regarding the lives of children who might have little other than a line in a census record to document them.