Black, Red, and Green: Abalone Shell Trade in the Ancient Southwest

Desert Archaeology project director Erina Gruner’s recent doctoral dissertation explored the exchange of ritual paraphernalia and exotic trade goods during the Chacoan and post-Chacoan periods (AD 875–1300) in the San Juan Basin, Here, she discusses the exchange of abalone shell by groups living in Arizona and New Mexico a thousand years earlier.

Southern Arizona is known for being a hub in prehistoric shell trade networks. While many people are familiar with the Hohokam shell industry and its focus on shells from the Gulf of California, connections with coastal California are less famous. However, a small number of Tucson-area sites dating to the Cienega phase (800 BC-50 AD) are notable for spectacular assemblages of Pacific coastal shell, particularly abalone. For example, Desert Archaeology’s 2019 excavations at Los Pozos, an Early Agricultural period (1200 BC-AD 50) settlement on the Santa Cruz River in Tucson, uncovered dozens of Pacific shell artifacts, mostly in mortuary contexts. The trails linking these early farmers on the Santa Cruz River with the fisherfolk of coastal California represent one of the oldest prestige trade networks in the U. S. Southwest. These coastal exchange networks were in flux throughout the prehistoric period, and multiple Southwestern “hubs” that acquired, consumed, and distributed Pacific abalone rose and fell in this time.

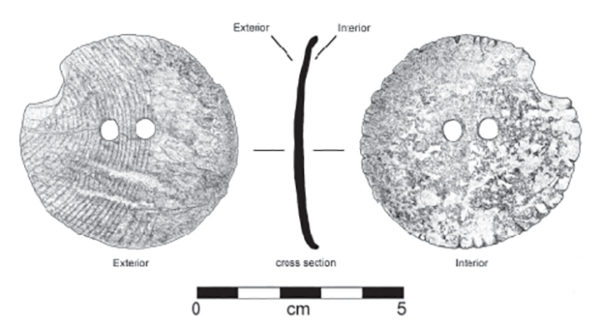

Abalone shell gorget from the Clearwater site, AZ BB:13:6(ASM), Tucson, Arizona (illustration by Rob Ciaccio).

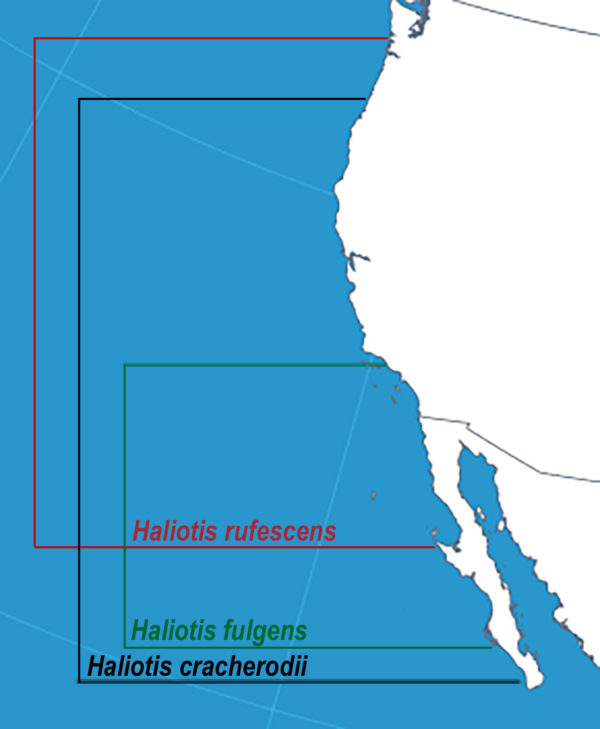

Three primary species of abalone are found at prehistoric sites in the Southwest: black abalone (Haliotis cracherodii), red abalone (Haliotis rufescens), and green abalone (Haliotis fulgens). Why ancient people here preferred one species over the other was conditioned by many factors, including (1) availability on the procurement end (what was fished in which Pacific coastal communities), (2) aesthetic preferences and beliefs of consumers in the Southwest, and (3) affiliations and alliances that structured access across the territory in between.

Most of the abalone used in the Southwest for most of prehistory sources to the Channel Islands and the coast immediately to the south. Dr. Chester King, who specializes in California shell ornaments, believes that most of the shell ornaments found in Early Agricultural period contexts in Arizona were produced in the Channel Islands and traded as whole beads. Prehistoric people in the islands fished both red and black abalone, although the availability of red abalone—which prefers cooler, deeper waters—varied according to climactic fluctuations, disease-related die-offs, and human overexploitation. Green abalone prefers warmer water. It isn’t common in Channel Island assemblages, or in ornament assemblages in most areas of the Southwest. When present, it suggests trade with people who lived on the far southern California coast or in Baja California.

Natural ranges of black abalone (H. cracherodii), red abalone (H. rufescens) and green abalone (H. fulgens) (figure by the author).

The question of prehistoric aesthetics and beliefs treads into the unknowability of past minds, but the third question—what historical processes structured access along trade routes between the Southwest and the Pacific coast—is more accessible.

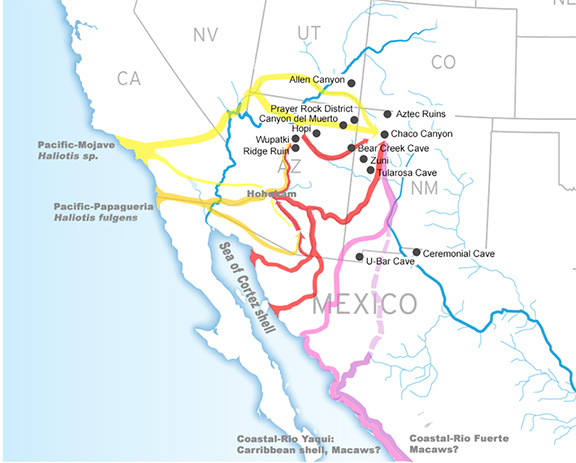

By the end of the Cienega phase (c. AD 50), trade in black abalone had expanded northwards to include Basketmaker communities on the Colorado Plateau that were ancestral to the Western Pueblo tradition. These northern neighbors may have acquired abalone through trade with partners along the Santa Cruz River in southern Arizona. Alternately, abalone at sites such as the Indian Hill Rock Shelter—located roughly halfway between San Diego and the Salton Sea—indicate an ancient northern trade route across the Mojave Desert. Linguistic reconstructions of population movements during this period suggest that this network could have connected Southern Uto-Aztecan speakers who produced beads on the California coast to related groups in southern Arizona, and to Northern Uto-Aztecan speakers who moved into the Western Pueblo region with the advent of maize farming.

These networks shifted after AD 500 with the expansion of the Hohokam culture in southern Arizona, and the rise of Chaco Canyon in northeastern New Mexico. The Hohokam expressed different preferences in shell than their Early Agricultural period ancestors. Although they continued to procure small amounts of abalone from the Pacific Coast, they favored sources in the Gulf of California. However, the rise of Chaco strengthened connections between the Pacific coast and northern territories. This period also saw a shift to local ornament production in the Southwest. Chaco hosted an impressive ornament industry, which procured and distributed black and red abalone on a scale previously unknown in the north.

The founders of early Chaco Canyon great houses were closely tied to regions to the south and west that were prominent in the preceding Basketmaker II-Basketmaker III (c. 500 BC-AD 720) Pacific shell exchange routes. The distribution of whole abalone shell versus finished abalone ornaments at Chaco Canyon great houses suggests that specific families that founded the earliest Chacoan great houses procured abalone, worked it into ornaments, and distributed it to their neighbors. The workshops were near ceremonial chambers and caches of ritual paraphernalia, and thus were tied to specific ritual roles and activities.

Black abalone “medicine dipper” from Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon. Catalog number H/3552 (photo courtesy of the Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History).

Around 1100 AD, things shifted. In the Chaco sphere, a new center called Aztec—in what is now northern New Mexico—rose and eclipsed older great houses at Chaco Canyon. While Aztec’s local influence was extensive, it was not a major distributor of Pacific shell. In the Hohokam area, Phoenix Basin platform mound villages welcomed immigrants from the north and the west. This cultural fusion produced new fashions in shell ornaments.

In between, Wupatki Pueblo—north of modern Flagstaff, Arizona—arose as a major hub in shell exchange networks, consuming and distributing large quantities of abalone. Wupatki was a multi-ethnic center, hosting local Sinagua populations, a handful of influential Chacoan immigrants, and some very well-connected traders with access to Hohokam exchange networks that were centered to the south in the Verde Valley. Together, they successfully diverted Pacific abalone trade from rising post-Chacoan centers such as Aztec, and replicated Chaco-type abalone ornament workshops in the west.

Ceramic period coastal-Southwest exchange routes (figure by the author).

This period also corresponds with shifts in shell species preference in these western exchange networks. For example, green abalone is relatively common near Wupatki. This species occurr in very low quantities in earlier Hohokam-area contexts, suggesting tenuous connections to the southern Pacific coast. While reasons for the rise of Haltiotis fulgens are murky, the pattern may be tied to internal shifts in the Hohokam sphere, which impacted their trade partners at Wupatki. Specifically, the 12th century arrival of Yuman-speaking Patayan immigrants at Phoenix Basin Hohokam centers may have created a “language bridge” similar to the initial expansion of Uto-Aztecan trade networks, connecting groups gathering abalone in northern Baja California to other Yuman speakers along the Colorado River and Phoenix Basin.

I’ll leave linguistics to the linguists. But for ongoing studies of Early Agricultural Period abalone ornaments, check back in in a year or two.

Resources

Erina Gruner’s dissertation, Ritual Assemblages and Ritual Economies: The Role of Chacoan and Post-Chacoan Sodalities in Exotic Exchange Networks, A.D. 875–1300, is available online at no charge.

Evolution of Chumash Society, by Chester King:

Regional Interactions between California and the Southwest: The Western Edge of the North American Continental System, by Erin Smith and Mikael Fauvelle