Fireplaces, Ovens, Roasting Pits: Cooking at the Tucson Presidio

Residents of the Tucson Presidio farmed, raised livestock, and occasionally hunted. Food was plentiful in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, but cookstoves were not. Historical archaeologist Homer Thiel explores the other ways people found for applying fire to food in order to transform raw ingredients into meals.

The Presidio San Agustín del Tucson was established in 1775, and Spanish soldiers began construction of the fortress in 1776. Between 400 and 500 people eventually lived at the Presidio. Feeding this population required growing crops and livestock on the adjacent Santa Cruz River floodplain. An 1804 report reveals that 600 bushels of maize, 300 bushels of beans and other vegetables, and 2,800 bushels of wheat had been grown in the previous year. Soldiers and civilians guarded 3,500 head of cattle (used for meat and milk) and 2,600 head of sheep (used for meat and wool). That year there were no pigs, although archaeological evidence indicates some were raised at other times, as well as chickens (mostly used for their eggs).

A few luxury foods were imported to the fort, brought more than 100 miles overland from stores located at Imuris and Arizpe to the south. These goods included rice, bottles and amphorae of wine, and slabs of chocolate. The latter was used to prepare hot chocolate (300 pesos worth in 1804). Presidio residents did not consume tea or coffee.

But how were foods cooked at the fort?

Today we use stoves that have burners on top and an oven below. The Presidio residents did not have this luxury (the first iron cook stoves did not arrive in Tucson until after 1856). Several archaeological features and artifacts provide evidence for how cooking was undertaken.

A corner fireplace (Feature 332) was found in a dwelling built near the west wall of the Presidio. The fireplace was made from a quarter-circle of molded adobe in the northwest corner of a room. The adobe was 8 to 13 cm high and had been built by hand. The fireplace was still filled with white ash from the last time it was used, and analysis of the ash revealed charred wheat, maize, and saguaro fruit seeds. The fireplace was likely used when it was cold outside and could also be used to heat the room. Jars and comales (tortilla griddles) could be placed onto rock trivets set in the fireplace to cook food.

A Sobaipuri Pima (Native American) bean pot, used to cook soups and stews, from the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson site (photo by Homer Thiel).

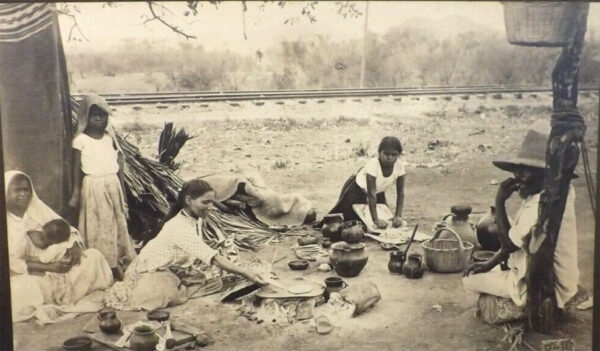

A historic photograph from Mexico from the Philadelphia Museums shows a woman making tortillas on a ceramic griddle perched over an outdoor fire. Other cooking vessels are nearby and another woman is grinding maize or wheat using a mano and metate.

An in-ground cooking pit (Feature 615) was found in the interior of the fort. It was about 80 cm in diameter. A thick layer of charcoal was at the base of the pit, with fire-cracked rocks lying on top. This was probably used to cook large pieces of beef.

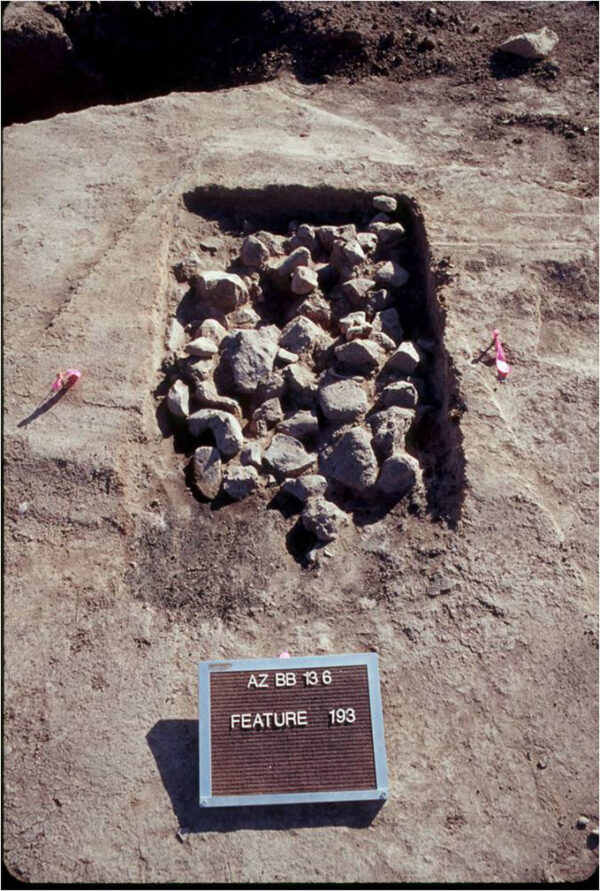

An in-ground roasting pit (Feature 193) was also found at the nearby San Agustín Mission, located on the west side of the Santa Cruz River. In this case, people had dug a shallow rectangular pit measuring 1.25 m long, 71 cm wide, and 19 cm deep. They laid a layer of mesquite branches and wood in the bottom of the pit and then covered it with rocks, although we don’t know if the wood was set on fire before or after the rocks were set in place. Cuts of beef were placed on top of the rocks. It is not known whether the meat was then covered to concentrate the heat or merely cooked on the rocks uncovered. In any case, when the meat was removed some of the cattle bones fell off and were left behind.

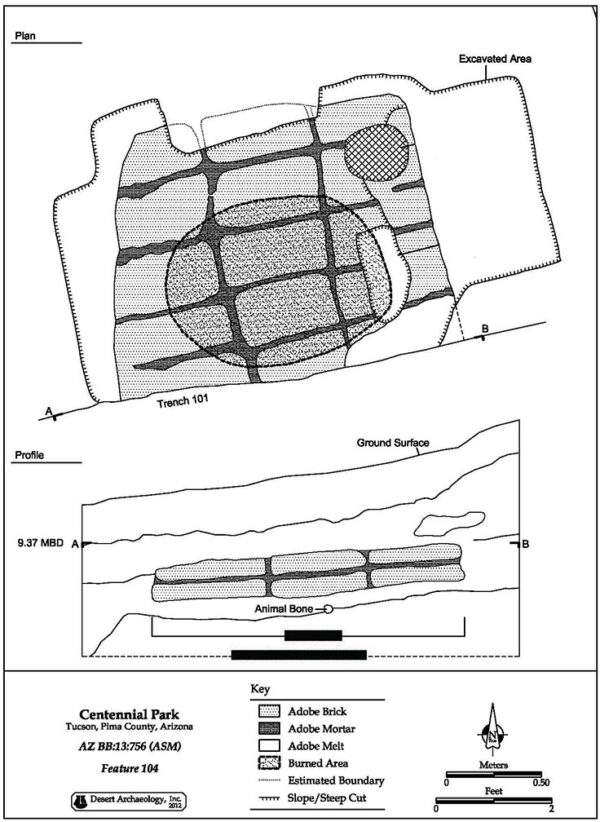

Presidio residents constructed adobe brick ovens to bake bread and other foods. The bases of two of these ovens have been found inside the fort and another immediately adjacent to it at the home of Francisco Romero and his wife Victoriana Ocoboa. At the Presidio Museum, a replica oven of similar design heats to over 500 degrees and can bake a loaf of bread in only a few minutes. Bread ovens could also be used to bake pastries and cakes.

The base of an adobe brick oven (Feature 104) found at the Francisco Romero homesite. The blackened area is the oven interior.

The Presidio Museum oven.

There are no surviving accounts describing how food was cooked during the Presidio times. Instead, archaeological projects have the yielded evidence of how meals were prepared. To learn more about what was eaten and how it was served at the table, see two previous Field Journal blog entries about diet and table settings.