The First Ice Cream in Tucson

Historical archaeologist Homer Thiel comes to the rescue with tales of cold, sweet historical relief from the heat.

Tucson and much of the rest of the Southwestern United States are undergoing record-breaking heat. In was hot in the past too, especially in early Territorial period (1856-1912) Tucson. One way to cool off was to find something cold to eat or drink, difficult in a place that did not have available ice. A somewhat remarkable entrepreneur was able to manufacture ice cream and sherbet in Tucson in 1875. Pieced together from newspaper articles, this is his story.

The origins of Francisco Forque, who also was called Francis Forque or Forques, are unknown. A person with the name of Francois Forque was in Quebec around the 1850s, and because he was referred to later as Monsieur, it is possible that this is the ice cream maker.

In any case, the first record we have of him is a newspaper article from Honolulu, Hawaii, printed in September 1871. We don’t know when he arrived there.

The Hawaiian Gazette (Honolulu, Hawaii), 13 September 1871.

Also remarkable, in the 1850s, ships would load up with ice in Boston and sail all the way to Hawaii, where they sold the ice for a profit.

Forque advertised his ice cream in a Honolulu newspaper in October 1871:

Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu), 7 October 1871.

Forque (listed as Mons. Forques) was a passenger traveling from Honolulu to San Francisco on the ship Per La Flore in May 1872 (San Francisco Examiner, 8 May 1872).

Within two years Forque had arrived in Tucson. He would have had to travel overland to get to Tucson, perhaps on a stagecoach or on a wagon. The railroad wouldn’t arrive for another five years (in March 1880).

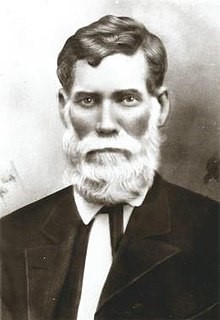

We don’t know exactly when he arrived, but by January 1875 something had happened: a fight between Forque and prominent local businessman Leopoldo Carrillo. Carrillo was one of the wealthiest men in Tucson, but was also known for unethical behavior. He was sued numerous times by people who claimed he had appropriated their money for his own use.

Tucson businessman Leopoldo Carrillo.

We have not been able to examine the court records due to the covid pandemic, but we know that Forque sued Carrillo for an assault that cost Forque one of his eyes. A jury trial was held, and Forque was awarded $2,000 in damages (just under $50,000 in 2021 dollars).

The next mention of Forque in Tucson was when he requested money from the Pima County Supervisors in April 1875: “The petition of Francisco Forque, setting forth that he was indigent and needed and asked relief, was denied in the grounds that sufficient cause did not exist” (Arizona Citizen, 10 April 1875).

By the end of the month, he was selling ice cream: “Francis Forque is at present supplying a very good article of ice cream to the public, at his place opposite Dr. Handy’s office. Give him a call and you will thank us for the suggestion. Take Juliet with you, on one of these beautiful nights, and visit Forque’s ice cream saloon and order one big dish with one spoon in it, and you may be happy yet.”

He charged 25 cents per one glass full, $1.00 for a pint, and $2.00 for a quart that “Will remain frozen long enough to be taken Ten miles… Fresh eggs wanted every day” (Arizona Citizen, 9 September 1876).

Arizona Weekly Citizen, 29 April 1876.

The Palace Hotel, April 1880 (photo from the Getty Museum; click image for information). The hotel stood on Meyer Street, near the current La Placita Park south of Congress Street.

There was no ice factory in Tucson until 1879. How did Forque make ice cream? He must have used a chemical process: “By the mid-19th century a number of freezing mixtures had been devised, which did not require snow or ice to start them off. They included such lethal cocktails as a mixture of sal ammoniac, nitre and water, said to reduce the temperature from 50F to 10F; nitrate of ammonia and water (50F down to 4F); and sulphate of soda with dilute sulphuric acid (50F down to 3F).” While not sounding very safe, it apparently worked.

The local Citizen newspaper editor really enjoyed his cool desserts:

Arizona Weekly Citizen, 13 May 1876.

The next month the Citizen suggested that you let Forque know that you only wanted one spoon, so you and your date could share it. This was apparently considered romantic, but in the days when diphtheria, cholera, tapeworms, and other intestinal problems were rampant in Tucson, sharing a spoon does not seem like a smart thing to have done.

Forque’s legal problems continued. He published a lengthy letter in the Arizona Weekly Citizen on October 21, 1876, recounting how Carrillo’s lawyers had threatened his lawyer, Briggs Goodrich. The lawyer in turn begged Carrillo to pay the sum he owned the ice cream maker, since he could not pay legal fees from the trial. Forque signed the document with an X, suggesting he did not know how to write his own signature. Father Antonio Jouvenceau witnessed the letter, indicating that the Catholic Church was behind his efforts.

Arizona Weekly Citizen, 14 October 1876.

The last advertisement for ice cream in 1876 was in September. Forque reopened his ice cream saloon in May 1877.

Arizona Weekly Citizen, 5 May 1877.

What happened to Forque afterwards is an unsolved mystery. He does not appear to have died in Tucson (he is not listed on the Catholic Diocese burial records). He is not listed on the 1880 census, although the census taker missed many people. Perhaps he went back to wherever he came from, continuing to make ice cream to help cool off people during the summer. By August 1879, Mr. M. Schutz, who had a candy and soda water business, received two “modern ice cream freezers” with the goal of making “some delicious ice cream soon” (Arizona Citizen, 1 August 1879).