Remembering Quintus Monier and Brickyard Workers

The upcoming opening of a new building prompts Desert Archaeology project director Mike Diehl to revisit an early Tucson architect, his brickyard, and the workers who made the bricks that built city landmarks.

In Autumn 2020, the Monier Building, a mixed-use 122 unit residential and 13,000 square foot commercial space, will open on Avenida del Convento in Tucson, west of the Santa Cruz River. Unless you are an architectural historian or a preservation archaeologist, the building’s namesake and his legacy may be unfamiliar.

Artist’s rendering of the Monier Building. Image from mercadodistrict.com/housing.

So who was Quintus Monier, and what did he do? I was fortunate to stumble across that question in 1995, entirely by accident, and to have the opportunity to chase down an interesting story about Monier, a brickyard (that I excavated in 1995, 2001, and 2005), and the people who worked at the brickyard to make the bricks that made Tucson. This is their story.

QUINTUS MONIER

In the late 1800s, Quintus Monier (1853-1923) immigrated from France to the United States in order to build the Basilica of St. Francis in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Quintus Monier and Family. Photo 62374, Arizona Historical Society.

The basilica was received with such acclaim that, in 1896, Monier was asked to build the St. Augustine Cathedral in Tucson. The Basilica of St. Francis was constructed from abundant local architectural-quality stone. Finding nothing similar in Tucson, and facing a shortage of timber, Monier started a brickyard. The St. Augustine Cathedral was constructed from bricks made from clay mined from the Santa Cruz River floodplain near the base of Sentinel Peak (A-Mountain).

St. Augustine Cathedral Under Construction, Tucson. Buehmann Photo B.92.788-92,791, Arizona Historical Society.

In addition to the cathedral, Monier used bricks from his brickyard to build the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad Roundhouse (still standing in Tucson), St. Mary’s Sanatorium (pictured at the top of this post), the Santa Rita Hotel, several buildings on the University of Arizona Campus, and many residential homes.

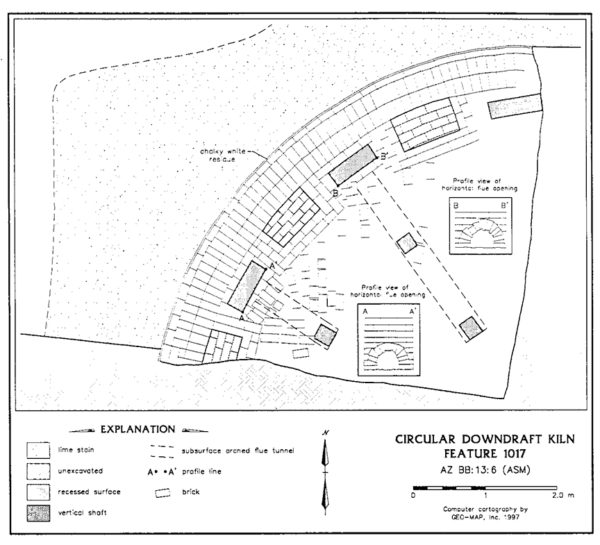

THE TUCSON PRESSED BRICK COMPANY

Monier later incorporated the brickyard as the Tucson Pressed Brick Company. It was the first and the longest-lived of several brickyards that mined clay and fired bricks west of the Santa Cruz River. If your Tucson home was made from bricks, was built between 1900-1966, and is located in the Barrio Libre or the Sam Hughes neighborhood, there is a good chance your house is made of TPBCo bricks.

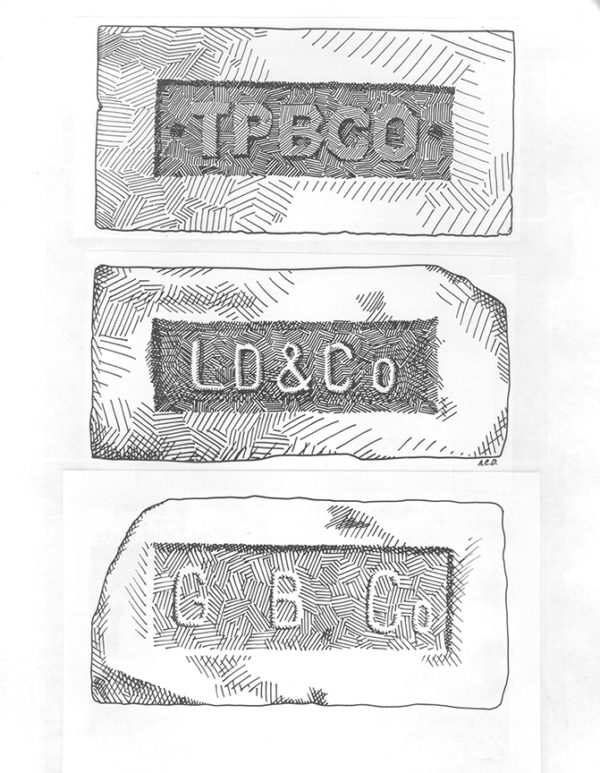

Bricks from Tucson brickyards. Top: Tucson Pressed Brick Company. Middle: Louis DeVry and Company. Bottom: Grabe Brick Company. Illustrations by Allison Diehl.

The Tucson Pressed Brick Company is gone, closing at the location near Sentinel Peak in 1966. It operated briefly in a new plant on Houghton Road but was shuttered forever in the early 1970s. The TPBCo buildings were subsequently demolished and more or less forgotten, until I had to excavate the brickyard (now a historic property), and a 3,000-year-old hamlet buried beneath it (but that hamlet is a different story).

LIFE AS A BRICK-MAKER

Fortunately, in 2006 I had the opportunity to ask a few retired brickyard employees about their experiences at the Tucson Pressed Brick Company. I spoke to Henry Machado, Ray Padilla, Frank Rodriguez, and Adelia Mejias.

In 1959, Henry Machado (far right, in hard hat) posed with a group of his colleagues at the Tucson Pressed Brick Company. Photograph shared by Guillermo Miranda, who is front-center with the sideburns.

I recorded hours of conversations and transcribed them. To my surprise, the brickyard workers and Mrs. Adelia Mejias had very fond, sometimes nostalgic recollections of the yard.

I asked all three workers about conditions and pay:

Henry Machado: “When I got married [1965] it was about $3.60 an hour. It was nice work making bricks. It was nice because I got out of the cotton fields working like this [indicates hunching]. I’d shuck cotton, pick it and haul it on out. We used to work ten hours. Picking the cotton was contract, but working the flowers was 35 cents an hour. We’d work ten hours.”

Me: The brickyard looked better than that?

Henry Machado: “Oh yeaahh! It was nice. You had to get up at four o’clock in the morning to get out there at five, five-thirty, but the brickyard was niiice [drawn out]. We ENJOYED it. [enthusiastic] Because all of us were together. It was just like a family. Everybody was there and we had to get along with everybody. It was nice! We were all together.”

Ray Padilla: “It was very hard work. Very hard. And the turnover rate was high, because it was hot and hard work. So guys would come and guys would go. But if you were poor and did not have much education the brickyard was there for you. It kept you working. And at the time, there wasn’t much for a poor, not-too-educated guy to do but go work in the mines, or at the air base.” [Ray and Frank then briefly discussed the mines and how, by comparison, the brickyard was good work, because at the mines they had to clean dirt and “slick moly (molybdynum) mud” from the earth movers using water and elbow grease.]

I asked Adelia about living so close to the brickyard:

Mrs. Mejias: “It was like a… like wind, like a big tunnel of wind, just blowing, blowing and blowing. You could… it takes getting used to it. So of course your dad and your mama would tell you all the horrible things so you won’t go out there to see what’s making that noise. [Note: And so Adelia told me the legend of La Llorona, and being a Maine Yankee, it was the first time I’d heard that ghost story.] We would hear it and it would bother us. But afterward we got to the point where we could run around and say “Ooh, this is where they’re doing” and “Oooh this is what they’re doing.”

Frank Rodriguez: “My dad said that they were.. They were gonna… they’d shoot oil in there and they had something.. something hot on that thing and it evaporated and created gas. They recovered the gas with something and that was burned. I dunno. He said something about something hot being in there and they used to inject oil in it. Well, maybe that was used as an oil kiln.”

Adelia Mejias’s grandson, Jacob, who was very young in 2006, joined our conversation:

Jacob: “Nana. Did you have chicken for dinner too?”

Mrs. Mejias: “Oh, we had chickens. We grew chickens, we grew rabbits. We had chickens, we had a chicken coop. We had rabbits too.”

Mrs. Mejias had more to say about living right next to the brickyard. About clothing so caked with brick dust that white shirts and underwear turned permanently pink. About not realizing she was “from a poor family” [note: with ten siblings] until she attended junior high school. About playing marbles, hide and seek, and being the top championship wrestler in challenges with her brothers.

I asked her if she had one thing she wanted to say about living there, and this is what she said:

Mrs. Mejias: “I think I learned to appreciate life and where I am right now, because of my upbringing. Because we were there. Because we were poor and it didn’t matter to us that we were poor. And then I decided, “Well, get yourself out and go to work and find a better life for you and your family.” And I have, right now I’m still teaching at school, I’m a teacher’s assistant at school. And I, um, I still go to school. I graduated from Pima [Community] College at the age of 65. And I’m still working. This is where I am now. Making their lives [indicates Jacob Mejias] richer by teaching them, what I know. I have six children and I think that my values… I have transferred my values. I brought up a great family. They are very nice.”

LOOKING BACK ON ALL THAT

As an archaeologist, I was lucky to be able to direct the excavation of the Tucson Pressed Brick Company, and delighted to research its connections with Quintus Monier, the cathedral, and other public works in town. Headline stories in the news and on web sites shine the spotlight on clever architects, builders, and industrialists, and so the Monier Apartments are justifiably named after Quintus Monier. He was a skilled craftsman, and a builder who solved some of the urgent needs for construction materials in Tucson.

But I cannot forget that the pending completion of the Mercado District’s Monier Building is, like the materials poured into and out of the Tucson Pressed Brick Company, the outcome of countless hours of work by people whose names are usually not recorded on any monument. For that reason, I count myself most privileged to have heard the parts of the story provided by Henry Machado, Ray Padilla, Frank Rodriguez, and Adelia Mejias.

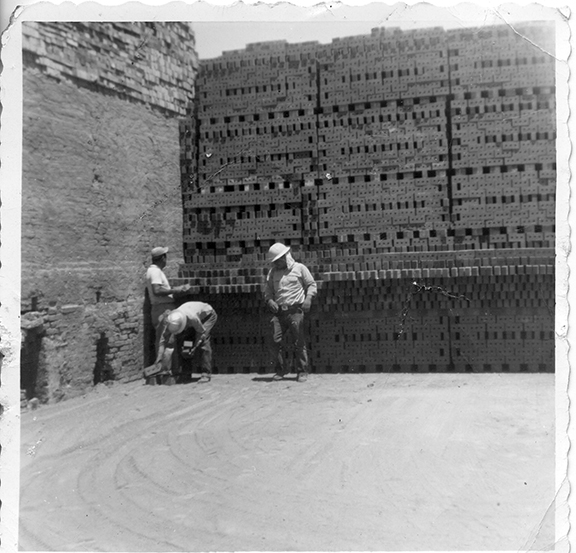

A scove kiln, and three TPBCo craftsmen, in 1959. Photograph shared by Guillermo Miranda.