From Here and There: Ceramic Petrography in the Deserts of the Southwest and Egypt

Dr. Mary Ownby, Desert Archaeology’s ceramic petrographer, discusses the ways petrographic analytical techniques can be applied to samples from very different times and places around the globe.

It may seem that pottery in the Southwest and from Egypt would have very little in common beyond the fact that both areas are deserts (keeping in mind that the Egyptian desert is just sand and rock, no lovely cacti or trees of any kind!). However, the kinds of research questions we ask of prehistoric pottery in both areas are the same. Where does it come from? How was it made? What is the meaning of pottery to the people here? How was pottery production integrated into the society?

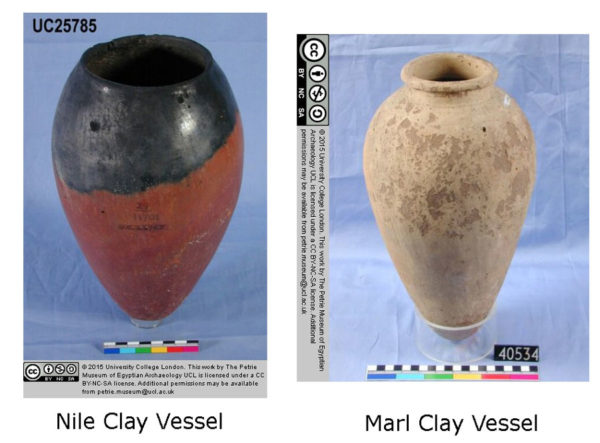

Petrographic analysis of pottery samples, using a special geologic microscope to examine thin sections of ceramics, can provide data to address these questions (see previous blogs about petrography and how we use it). In the Southwest, we have used the geologic diversity of pottery raw materials (mostly clay and sand) to refine provenance (place of origin) assignments and clarify exchange of vessels. Information on how pottery production was organized and differences in raw material selection are now well known. Egypt does not have this diversity and in fact, the use of Nile clay for much pottery means provenance work is challenging as this resource is broadly available with little variability. The other preferred clay type is a calcareous clay acquired from the erosion of limestone deposits. Such deposits are found on both sides of the Nile Valley, the Delta, and in the Western Desert oases. Likewise, shale clays used for making pottery are found in the southern half of the Nile Valley and in the Western Desert oases. However, pottery production in the latter areas has recently been clarified through my work on the petrographic analysis of kiln samples from Kharga, Dakhla, and Bahariya (soon to be published, in the French journal Cahiers de la Céramique Égyptienne 12). Also, clarification of the kaolinitic clays in the Aswan areas has been done (see Resources, below). This new data has enabled much more to be said about pottery production and distribution in Egypt.

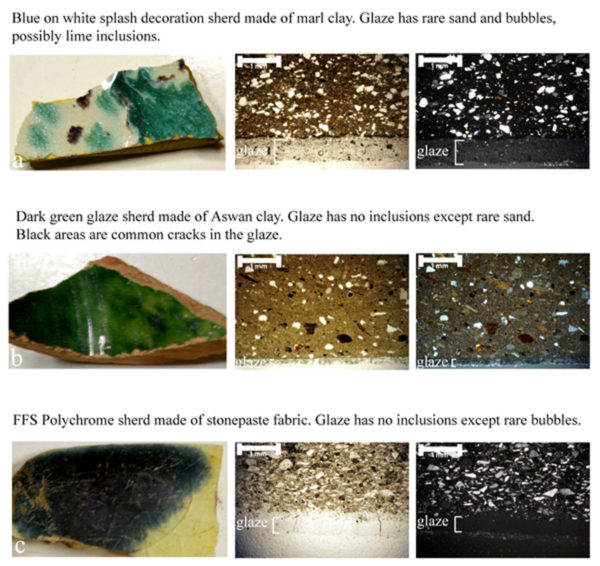

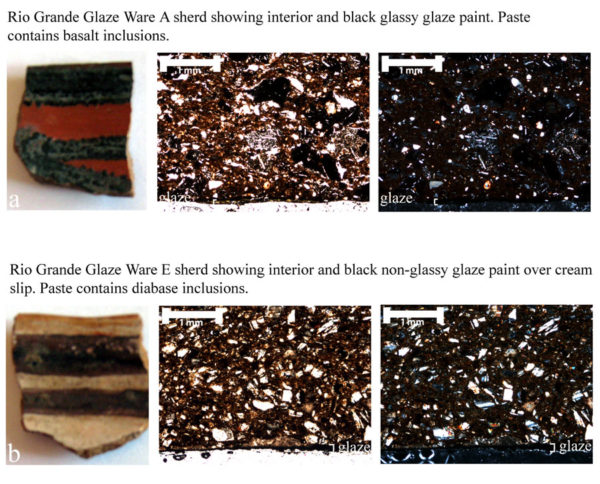

In fact, a recent article I co-authored in the Journal of Archaeological Science Report series (see Resources, below) discussed the manufacture of Egyptian Medieval Glaze Ware (9th to 15th centuries AD) and New Mexico Rio Grande Glaze Ware (14th to 18th centuries AD) together. What could possibly connect wares from opposite sides of the globe? An investigation into the technological transfer of glazing knowledge. Using the petrographic analysis to group the samples by paste recipes, the glaze features were also characterized as seen in thin section. There was a clear connection between where the pottery was made and the type of glaze.

In Egypt, green-glazed sherds were made in Aswan with a lead glaze, splash decorated vessels were made with calcareous clays and probably an alkali glaze, and Fustat Fatimid Sgraffiato sherds were made of stonepaste and had a lead-alkali glaze.

In New Mexico, several Rio Grande Glaze Ware sherds with a basalt sand had a vitrified (glassy) true glaze paint, while the later sherds with a diabase sand had an unvitrified glaze paint.

Given the very different social, political and economic contexts, what does this say about how people learned glazing methods? In Egypt, the industrial production of Medieval Glaze Ware meant that glazing knowledge, first developed in the Near East, could be directly acquired by Egyptian potters. They would then have needed to adapt the recipe to their local raw materials, but they could acquire the glazing ingredients easily through extensive trade networks. Thus, the Egyptian Medieval Glaze Ware was produced to a high technological degree and was nearly identical to such pottery produced elsewhere in the Near East. In the decentralized pueblos of New Mexico, potters in the southern Piro Pueblos may have indirectly acquired the knowledge for producing glaze paint from northern pueblos through seeing such vessels circulated among the pueblos. This may have resulted in the poor production of lead paints by specialists along with issues in acquiring the proper raw materials due to the Spanish missions limiting people’s movements. Overall, this study shows how petrographic analysis of pottery from here and there can give us a great insight into how pottery was made under different socio-economic systems.

Resources

Ownby, Mary F., Evan Giomi, and Gregory Williams

2017 Glazed ware from here and there: Petrographic analysis of the technological transfer of glazing knowledge. Journal of Archaeological Science Reports 16:616-626.

Peloschek, Lisa

2015 Cultural Transfers in Aswan (Upper Egypt). Petrographic Evidence for Ceramic Production and Exchange from the Ptolemaic to the Late Antique Period. Unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Vienna.