On Having Nice Things: Preservation, Outreach, and the Honey Bee Archaeological Preserve

On the public opening of the Honey Bee Archaeological Preserve, we post R. J. Sliva’s piece on the delicate balancing act of archaeological preservation and public outreach, written over the span of a few months last summer while monitoring the construction of the preserve’s access trail.

“So… how is this gonna work, anyway?”

It is a hot morning in May of 2017, the sun having climbed up from behind Pusch Ridge a few hours ago and chased the birds to what shade they can find in the mesquites and cholla. I am in the Honey Bee Archaeological Preserve in Oro Valley, a 13-acre parcel isolated by a low block wall from a surrounding housing subdivision near the intersection of Rancho Vistoso Boulevard and Moore Road. Outside the wall, dozens of new houses stand shoulder to shoulder while heavy equipment rumbles in the remaining open spaces, stripping the dirt and flattening the land to build more. Inside the wall is the central area of Honey Bee Village, a Hohokam settlement built and lived in by dozens of families at a time over a 550-year span, from roughly AD 650 to 1200. The preserve is ringed by the trash mounds built up over centuries as household detritus was discarded, and holds both a ballcourt and the stone foundations of a later compound. Aside from damage by pot-hunters over the years, it hasn’t been excavated, its hundreds of residential structures left undisturbed.

Today I’m sitting next to Mark, a Pima County Parks equipment operator, on the front seat of a Bobcat we have slowly maneuvered from a small gate in the wall to the middle of the preserve, following a winding route that snakes between trash mounds in an attempt to disturb as little of the surface deposit as we can. Finding space between the mounds is relatively easy, but avoiding artifacts is close to impossible. The entire site is carpeted with things left behind by the people who lived here a thousand years ago, and in many places it is difficult to take a step without treading on one of the hundreds upon hundreds of Hohokam plainware pottery sherds that litter the ground, interspersed with the occasional decorated sherd, metate fragment, piece of flaked stone, or broken shell.

We have been out here for a week now, equipment man Mark carefully hauling and placing piles of rock at different spots where erosion has been damaging the site, me monitoring to make sure the Bobcat and the rocks stay in their pre-approved tracks and staging areas. In a few days, Arizona Conservation Corps crews will arrange the rocks into low-profile erosion-control structures to diffuse waterflow across the site, making it easier for rainwater to percolate into the ground and preventing more incised channels from forming. This in turn is in preparation for county crews to return later in the spring to build an interpretive trail that will provide public access to the preserve and its marvelous carpet of artifacts.

Mark’s question—how is this going to work, anyway—is specifically about how the county will manage to allow people in here while keeping them from carrying half of the site out in their pockets when they leave, but the longer I am out here, the more I understand how the question applies to every aspect of the project. This is more than an engineering problem, more than an archaeological challenge, more than an experiment in public outreach and education. It is an exercise in finding a balance among opposing factors that are aligned in multiple planes, and then realizing the fulcrum needs to be shifted this way or that, and again, and then again, with no guarantee that today’s best solution will be anywhere in the ballpark a month from now.

The preserve itself represents the most obvious balance of contradictory forces in play here. Archaeological preservation must be balanced with economic development. Profit from building houses must be balanced with the cost of required archaeological mitigation. The developer of the modern housing being built over most of Honey Bee Village donated 13 acres of prime real estate in the center of the tract to Pima County, protecting the core of the site from development into perpetuity (and giving up the potential profits to be gained from the same). In return, the county covered the cost of archaeological data recovery required by antiquities protection laws on the rest of the site—a bright spot for archaeology in an area that has been consumed by development over the past two decades.

A broken basin metate on a scattering of sherds near an incised channel in the preserve. Note the large rim sherd in the lower right corner.

The other balancing acts are less obvious until you are standing on the ground making decisions that will determine what the preserve will look like in the immediate future as well as ten years down the road. The fundamental decision facing the county and the Native American descendants of the original Honey Bee Village residents was how to balance the desire to let nature take its course with the desire to preserve the site as a cultural resource. Now that all parties have agreed to preserve the site, the need to prevent further damage from natural processes must be balanced with the incidental damage from equipment and footfalls that is an unavoidable byproduct of human intervention.

Erosion is damaging the site and, left unchecked, will dump a significant portion of it into the Cañada del Oro wash before the end of the decade. Flood control personnel have developed methods to slow erosion and preserve the archaeological features with structures that are built of natural materials and designed to be as unobtrusive as possible. These corrective measures are necessary for the protection and healing of the landscape but, like knee braces and stitches, leave their own abrasions and scars in the process.

Arizona Conservation Corps crew members building one-rock dams across a drainage in the western portion of the preserve.

Installing the erosion-control features requires multiple trips to move rock by Bobcat, wheelbarrow, and boot-wearing humans, all of which unavoidably leave tracks that cut into the ground surface. The flood control engineer would like to dig shallow footers for the rock checkdams to maximize their effectiveness, but our agreement with the descendant communities prohibits digging, so she agrees to leave the dams laid atop the surface of the ground and hopes that the native plants seeded between the rocks will grow quickly and their roots will compensate somewhat for the lack of a sub-surface installation. We step as gently as we can, and I carefully scoot artifacts I see in the Bobcat’s tire tracks to spots just outside its path so they won’t needlessly be pulverized—another balancing act between preserving archaeological context and preserving artifacts, decided on the fly in favor of the artifacts. There is no perfect solution here that will satisfy all parties.

A plainware sherd in plain view, and a red-on-brown decorated sherd half-hidden in the shadow of a rock on the surface of a trash mound in the preserve.

The most vexing dilemma for me as an archaeologist? The benefits of educating people by publicizing the site and the trail must be balanced with the potential losses incurred if even a small number of visitors respond with avarice instead of wonder. And this is where we come back to the question that opens this piece, the same question that arises in every conversation I have had this week with members of the construction crews, with the county engineer, with relatives visiting from out of town.

How is this going to work?

The unspoken subtext of that question, of course, reads more like “how are you going to keep people from stealing everything they see?” Curious neighbors have already walked in through the preserve’s open gate, following the Bobcat tracks to ask what we’re doing and why we’re modifying the site, even if it’s being done with natural materials and a minimalist approach. Levels of satisfaction with my answers have been variable. It may be the most delicate balance we need to strike—to preserve archaeological resources, we need to publicize them. When we publicize them, we run the risk that they will be damaged or destroyed.

Why, then, are we doing this at all?

A fragment of marine shell residents of Honey Bee Village acquired via trade from the Sea of Cortez or the Pacific Ocean.

The answer has to be because we believe that once people experience the site, they will value it.

We understand that it’s difficult to become passionate about preserving things that are mostly theoretical, or to develop a sense of community pride in a past that is mostly experienced as a lecture or picture on a sign. Without public pride and passion, legislation and funding lag behind, and irreplaceable things are lost forever. Visitors to Tucson often hear about our rich archaeological heritage, but this is the land of pithouses, not cliff dwellings, and we have yet to innovate an effective preservation system for holes dug in the ground. There is precious little standing prehistoric architecture left in the our part of southern Arizona to spark people’s imaginations and fan their enthusiasm.

A stone flake that was used as a cutting tool by a Honey Bee Village resident. Note the sheen of usewear along the curved edge on the left.

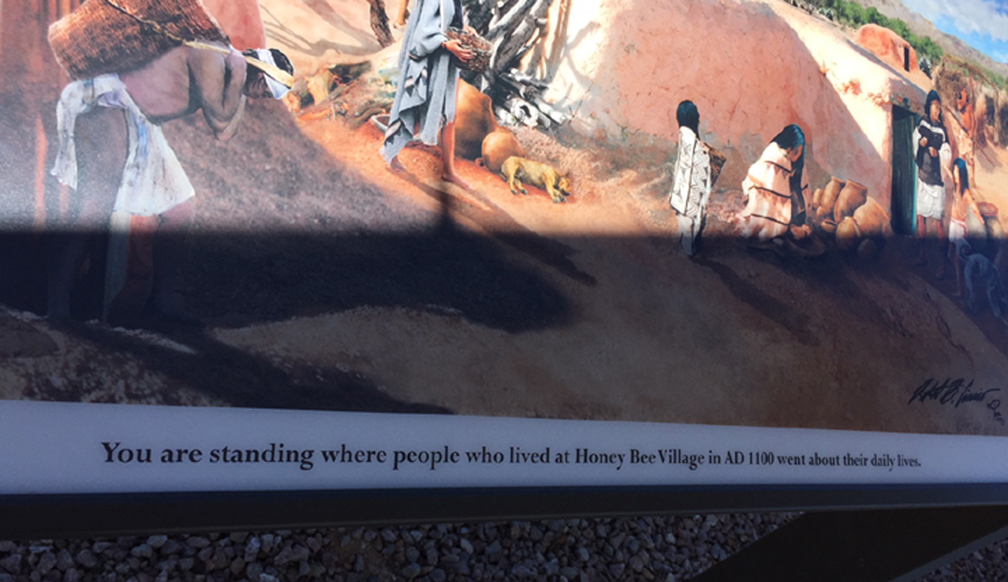

So the county innovates here in this remarkable place in this way: presenting the site not as a postcard-perfect museum, but as an opportunity to view Honey Bee Village through the archaeologist’s eyes, requiring visitors to slow down, think about the people who lived here, and look for the subtle clues that tell us what ordinary things they did from day to day. Train your eyes to discern the angular edges that make the potsherd pop into view against the same-colored desert floor. Read the slight undulations of the ground that signal the presence of a centuries-old trash mound. Catch a glimpse of small sherds scattered in the ashy dirt kicked up next to a ground squirrel’s burrow and think about rodents tunneling down through time, bringing bits of the past back up to the sunlight for the first time in a millennium. Look at the Santa Catalina mountains and think about walking the two and a half miles across the desert to get to the foot of the trail that leads to the top, think about the hike up, and think about the walk back across that two and a half miles, only this time carrying the Ponderosa pine logs needed to build the pithouses people lived in here. Pause by the ballcourt, picking its subtle raised berms out of the cholla and mesquite, and imagine the shouting and excitement as the ballgame unfolds and travelers from distant settlements unroll hides and open baskets full of trade wares.

It’s an exercise in observation, in imagination, in connecting a hundred different dots to get a fleeting glimpse of the past that has been bladed away outside the preserve’s walls.

Right now the trail and checkdams might look a little raw, but give us one monsoon season and many of the erosion-control measures will begin to blend back into the desert. Dead tree branches wedged into small channels will catch additional plant material that washes over them, which in turn will trap sediments (and hopefully a few brittlebush seeds) and fill the channels. The native grasses and forbs that were liberally seeded among the rocks in the dams will sprout and grow. We cannot stop erosion, but we can slow it, and the tracks we’ve left will eventually fade.

That’s the easy part. For the rest, we hope. We hope that visitors to the preserve will respect the signs exhorting them to look with their eyes only and leave the artifacts they see for the next visitors to discover. We hope that the neighbors will treasure this unique cultural resource in their midst and take such pride of place that they will self-police. We hope that each visitor realizes that the tiny piece of decorated pottery they see half-hidden under a cactus is there for them to see because the last person who saw it left it in place. And we hope they in turn leave it so that the next visitor and the next can experience their own thrill of discovery, their own little reward for taking a patient, close look at this place where so many people walked centuries before them.

Epilogue: March 23, 2018

It’s a perfect morning at Honey Bee Village, with a blue sky and enough breeze to keep the sun at bay. The site has been blessed by an elder of the Tohono O’odham Nation, songs offered, the ribbon cut. The first visitors have walked around the trail and asked plenty of questions of the volunteer docents from Desert Archaeology. Everyone’s smiling.

The artifacts are still there on the ground, ready to tell stories of the people who lived here to the next visitor who comes through. It’s a nice thing.

Resources

Southwest Photo Journal story on Honey Bee Village and Archaeology Southwest’s pithouse reconstruction

The Town of Oro Valley’s Honey Bee Village website