Desert Archaeology-Partnered Field School Wins Diversity Award

Homer Thiel reports this week on recognition for the Guevavi field school. The Gender and Minority Affairs Committee was established to foster diversity and equity within the Society for Historical Archaeology and promote consideration of issues relevant to under-represented groups. The field school competition awards programs that increase participant diversity and/or address issues and themes related to diversity.

In January 2017, the University of Arizona’s Guevavi Mission Field School received the Society of Historical Archaeology’s Gender and Minority Affairs Committee’s Diversity Field School Award. The field school was a joint project led by Dr. Barnet Pavao-Zuckerman of the University of Arizona (now at the University of Maryland), Homer Thiel of Desert Archaeology, and Jeremy Moss of the National Park Service.

The Mission Los Santos Angeles de Guevavi was established in 1691 by Jesuit priest Eusebio Francisco Kino at an existing O’odham village located along the Santa Cruz River, close to the modern Mexican border. He and the priests that followed him had several goals. They were interested in converting the residents of Guevavi to Christianity. They wanted the residents to raise Old World domesticated animals(cattle, sheep, and horses) and a variety of plants including wheat, peaches, and quince. Surplus animals, grain, and produce could be sold to raise money to operate the mission, as could manufactured goods such as the beef tallow obtained by boiling cattle bones.

Initially, villagers showed little interest in raising animals because it conflicted with their annual movement across the landscape. However, they eventually took up large-scale ranching. A church, convento, and dwellings were constructed at Guevavi beginning in 1751. Apache raids led to the mission being abandoned in 1775, moving to the north to Tumacácori. Yaqui miners are known to have used the complex in the 1810s, but afterward the adobe structures slowly melted away.

Eight acres of the site are owned by the National Park Service (NPS) and are a unit of the Tumacácori National Historical Park. Forty other acres are owned by the City of Nogales. In 2011, Desert Archaeology mapped the site. It was noticed that animals were burrowing into the Mission-era trash midden on the NPS parcel, bringing artifacts and animal bones to the ground surface. Charcoal-stained earth visible on the surface of a dirt road on the City of Nogales property appeared to be prehistoric pit structures and roasting pits, actively eroding away from traffic and rainfall. The road also crossed over a low dirt mound that was believed to be a Spanish-era structure.

NPS archaeologist Jeremy Moss contacted the University of Arizona, and the U of A’s Barnet Pavao-Zuckerman suggested that they form a team with Desert’s Homer Thiel to teach an archaeological field school at the site. Field schools teach students basic archaeological techniques: how to dig, how to complete field forms, and how to draw plan maps and profiles. From 2013 to 2015, 30 students excavated during short field seasons at Guevavi. Each student also worked on a separate research project, portions of which were incorporated into the final technical report. The unique team of co-directors meant that students were also exposed to the three primary career paths for archaeologists in the United States: federal agencies, cultural resource management firms, and universities.

Several significant discoveries were made:

* The trash midden contains stratified deposits from the Mission and Yaqui miner occupations. It yielded the oldest peach pits and chile pepper seed yet identified in Arizona. Also found were local Native American ceramics and items imported from Mexico, Europe, and China, revealing the local and global economic interactions of the Spanish missionaries and the residents of the site. Animal bones recovered were mostly cattle, with smaller quantities of sheep or goat, and few wild species, suggesting that Mission residents rapidly adopted Old World animals.

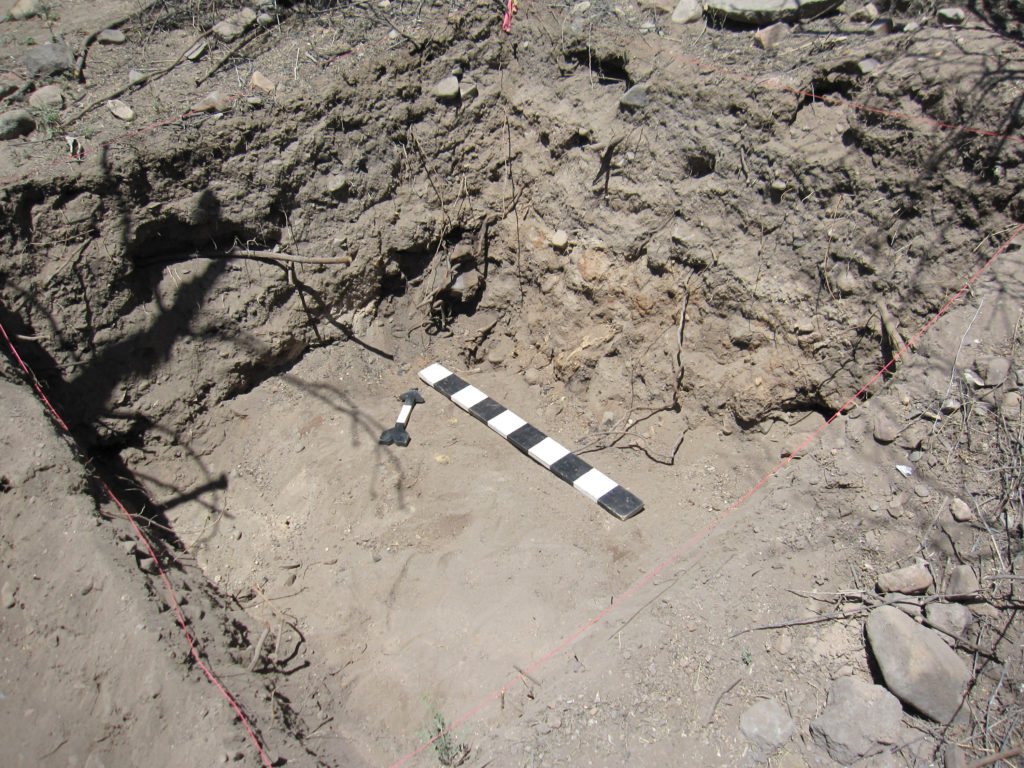

A unit in Feature 26, a historic period trash midden, that yielded large amounts of animal bone, plant remains, and artifacts.

* The low mound turned out to be a Spanish-era dwelling that was burned after it was abandoned.

* Two nearby large light-colored soil areas were found to be a livestock pen and chute complex and the Mission corral. These may be the best-preserved examples of Spanish animal husbandry features in the United States.

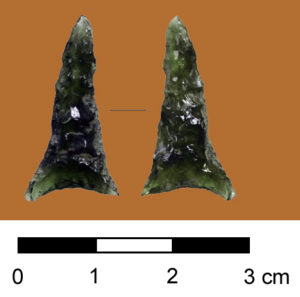

* A large Hohokam Colonial and Sedentary period site is present, with occupation dating to A.D. 800 to 1120. Numerous pit structures and roasting pits lie beneath the road and nearby areas. Artifacts from the Gila River in Arizona, modern-day Mexico, and the Pacific coast reveal extensive trade networks.

Feature 27 was a rock-lined roasting pit dating to the Middle Rincon phase of the Hohokam Sedentary period (about A.D. 1075).

Many people helped make the field school a success. Among them, the Tohono O’odham Nation provided Native American monitors for the project. The NPS Home Office sponsored a “Linking Hispanic Heritage Through Archaeology” program that provided 22 high school students an opportunity to learn about archaeology. Since attending the field school, University of Arizona students have gone on to graduate school at the University of Arizona and the University of Glasgow in England, with another individual working as an archaeological technician for the United States Forest Service.

The GMAC Diversity Field School award is part of the Society for Historical Archaeology’s efforts to make “the field… more inclusive of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, abilities, and socio-economic background.” The Guevavi field school students came from diverse backgrounds, yet worked together to accomplish the goal of documenting the archaeological resources of the Guevavi Mission site.

Resources

Society for Historical Archaeology Gender and Minority Affairs Committee (scroll down to see previous Diversity Photo and Field School Award winners)