The Westside Canals

Archaeological work on the west side of the Santa Cruz River, to the north and south of West Congress Street, resulted in the documentation of the long history of water management in this area. What has been found? Homer Thiel provides answers.

Pre-Contact ditches and canals

The oldest irrigation ditch found in Tucson has been radiocarbon dated to 3,500 years ago, which places it in the Silverbell Interval (2100-1200 BC) of the Early Agricultural period (2100 BC-AD 50). This and several other Early Agricultural period canals are generally quite small. At the Clearwater site (near the base of Sentinel Peak/”A Mountain”) they fed water to small, sunken field plots where maize was raised. Nearby, the people who lived at the site built clusters of pit structures and, in two areas, larger structures where ritual or administrative activities likely took place.

The construction of these canals probably was a group effort, with one or more individuals supervising the work of other people. The canals had to be periodically re-dug or repaired after monsoon floods. When in use, the farmers made small openings in the sides of the canals, directing water into individual field plots or into smaller ditches running to groups of plots. The discovery of an Early Cienega phase (800-400 BC) cemetery suggests the inhabitants of the site were staking a firm claim to the land where they were growing maize.

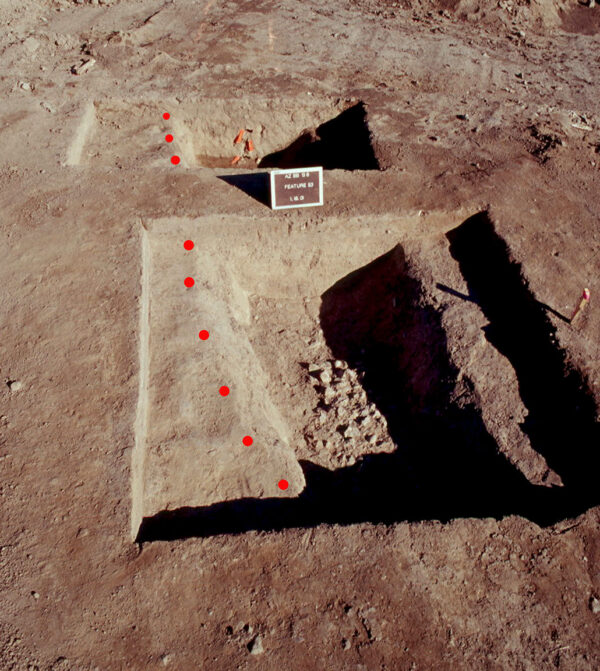

An Early Agricultural period canal at the Mission Locus of the Clearwater site. It was lined with fire-cracked rocks, perhaps in an effort to stop erosion. The red dots indicate the left edge of the canal, running from bottom to top in the frame. (photo by Desert Archaeology)

The Clearwater site was also occupied during the Early Ceramic period (AD 50-500). Canals dating to this period at the site have not been identified, perhaps because they were re-used and reconfigured by subsequent Hohokam residents. Numerous Hohokam canals were found snaking across the western floodplain in this area. Along the west side of what is now Mission Garden, close to the base of Sentinel Peak, was an enormous canal, the largest found thus far in the Tucson Basin. It was 7.6 meters wide and 2.2 meters deep (about 25 by 7 feet).

A profile of a large Hohokam canal. The base is stained with manganese, which develops as water seeps through the base of the canal. The visible layers are sediments that were deposited as the canal was used and during floods (photo by Desert Archaeology).

Scattered among the canals are solitary pit structures, which archaeologists call field houses. These may have been temporary residences for the people tending fields. In the mid-1950s, National Park Service archaeologist George Cattanach observed large quantities of Hohokam pottery to the south and east of Mission Garden, suggesting a large village had been present there. Unfortunately, the area was subsequently destroyed by the city of Tucson for a landfill. During Desert Archaeology’s work in Mission Garden, we found remnants of Hohokam houses—mostly hearths that were deep enough to survive historic period plowing.

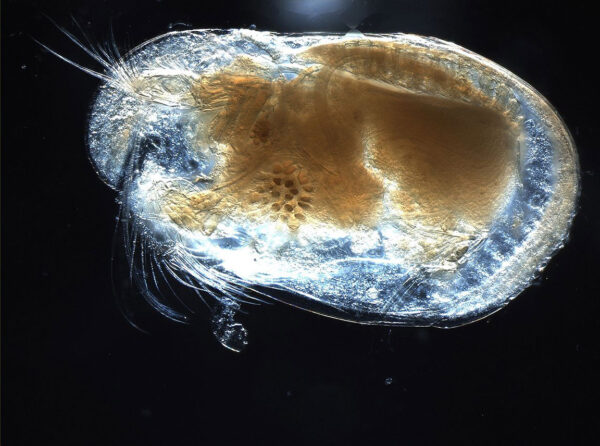

Ostracodes

When we excavate canals, we take small soil samples from throughout their profiles that paleoecologist Dr. Manuel Palacios-Fest processes to recover ostracodes. These are tiny molluscs, their shells hardly visible to the naked eye. Different species of ostracodes prefer different water environments. Some like warm water, while others live in cooler water. Some prefer fresh water, and some live in more saline water. Some like fast-flowing water, and of course there are other species that live in calm water. Palacios-Fest identifies the species found in prehistoric canals, which tells us what the conditions of individual canals were and how these conditions changed through time.

Spanish, Mexican, and American Territorial period canals

Father Eusebio Kino and Captain Juan Manje traveled up the Santa Cruz River in 1697. At the O’Odham village called S-cuk Son, located at the base of what today we call Sentinel Peak, Manje reported: “Here the river runs with much water… there is good pasturage, and agricultural land with many canals to irrigate it. From this land they harvest much maize, beans, cotton from which they make their clothing, and other fruits of squash, cantaloupe, and watermelon.” Watermelons and cantaloupe are Old World crops. Their seeds were brought over to Mexico and then passed by Native Americans from village to village north, arriving before the Spaniards.

The Spaniards referred to the canals as acequias, a Spanish term for community-operated canals. The acequias watered the fields of Native Americans and then, starting in 1776, the fields of the Spanish soldiers and their families after they built the Presidio.

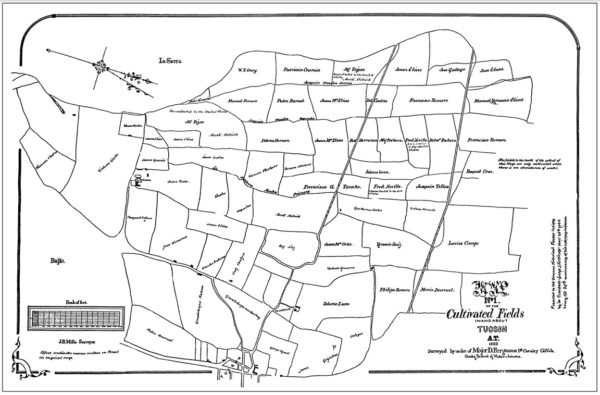

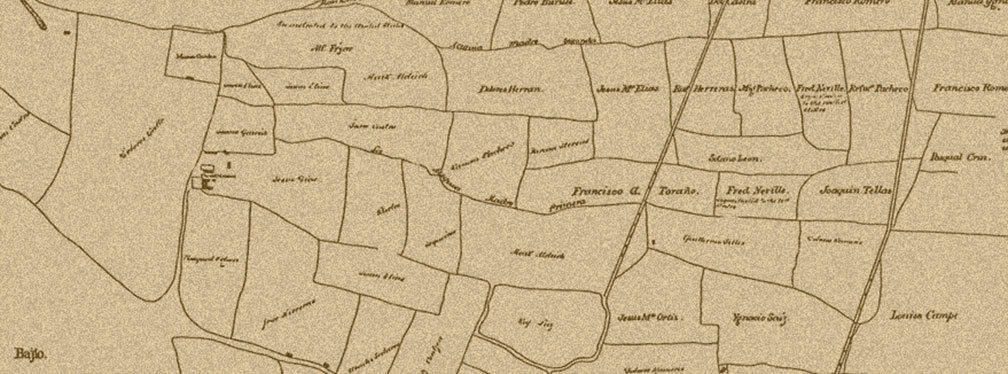

In 1862, the Union army occupied Tucson, taking in back from the Confederates. Major David Fergusson, planning to confiscate properties of Confederate sympathizers, then had John J. Mills draft two maps. One map showed the downtown area. The second was titled “Map No. 1 of the Cultivated Fields in and about Tucson A.T. [Arizona Territory]” The map shows dozens of fields, labeled with the names of their owners. The two east-west roads depicted are today West Congress Street and St. Mary’s Road. A handful of buildings are noted, as well as the San Agustín Mission complex and Mission Garden. Sentinel Peak is called La Sierra.

The three major canals are labeled Acequia Madre Primera, Acequia Madre Segunda, and Acequia Madre Tercia. The field boundaries are likely smaller canals running off of the three larger ones.

A zanjero was elected by the field owners to regulate the flow of water through the canals. He would inspect fields and determine which ones needed water. This system worked well until the mid-1880s, when certain property owners began to use more water. These included Solomon Warner, who had built a dam at the south end of Sentinel Peak to collect spring water for his mill, and Leopoldo Carrillo, who was renting his land to Chinese gardeners who were growing water-thirsty crops. The zanjero cut off water to the fields north of St. Mary’s Road, and a lawsuit ensued. The judge determined that age-old water rights were no longer applicable.

A few years later Samuel Hughes dug a deeper canal on the north side of St. Mary’s Road. During the monsoon season of 1889, the river began to erode downward, the deeply entrenched water course cutting off the water supply of the other canals. Eventually the Allison Brothers installed large pumps that pulled groundwater out and deposited it into cement-lined canals. This allowed farming to continue along the west side, lasting into the 1930s.

Recently the folks at Mission Garden created a new demonstration acequia that runs water through the middle of the garden. It is stocked with Gila topminnow, an endangered species that once thrived in the Santa Cruz River.

The area watered by acequias on the west side of the Santa Cruz largely has been developed, covered with housing and businesses. Traces of the canals and fields still lie hidden in undisturbed areas.