Baskets, Jars, Pits, and Platforms: Solving Storage Problems in the Ancient Southwest

Homer Thiel explores how people living in the ancient Tucson Basin stored their food and goods before the advent of closets and SnapWare. The featured image above is from Rob Ciaccio’s reconstruction of lifeways at Honey Bee Village (see the link at end of this post).

Recently a movement has developed that encourages us to de-clutter our homes, to empty out our closets of things that do not “spark joy.” For the people who lived in Arizona before the Historic period (AD 1694), this was less of a problem. People had fewer possessions, and the ones that they had usually did not take up a lot of space.

But people still needed to store things. They needed to store seeds for next year’s crops. They needed to store the harvested crops and collected wild food. They needed to store dangerous items, like sharp spear and arrow points, out of the reach of children. And they needed to hide items for those times when everyone left their settlements and traveled to other places to gather food or to watch a ceremony or game at a ballcourt or platform mound. Archaeological excavations at Early Agricultural, Early Ceramic, and Hohokam era sites have found that the people who lived during these different time spans had different options for storage.

The Early Agricultural period (2100 BC to AD 50) saw people living in small villages for part of the year, tending irrigated fields. At other times they were probably moving out onto the surrounding landscape to harvest wild plant foods, such as saguaro fruit, or to hunt deer and bighorn sheep, which were more likely to be found away from settlements. The Early Agricultural people needed to store harvested crops and to disguise the location of heavy items that could be carried away from the untended village by other people.

Reconstruction of irrigated fields near an Early Agricultural period settlement near the Santa Cruz River, Tucson, Arizona (by Robert Ciaccio).

These people used baskets and bags made from animal hides to store many things. Unfortunately, storage containers made from perishable materials are rarely preserved, except in caves, but we have evidence that these items were being manufactured in many villages. Baskets and bags could have been hung from the roof beams inside pit structures. We occasionally find sharp objects such as bone awls and dart points in burned roofing materials, suggesting they had been stuffed into the thatching of pithouse roofs. This would have kept these items out of the reach of the inquisitive hands of small children.

Although baskets and bags likely were used for temporary storage inside houses, many of the Early Agricultural period pit structures we excavate have large storage pits inside them. Sometimes the pits take up almost the entire floor space, suggesting that the structure was being used only for storage. In one case at the San Agustín Mission locus of the Clearwater site (west of downtown Tucson), the walls of the storage pit had been hardened by building a fire inside it, the heat from the flames converting the surrounding clay into an almost pottery-like consistency.

A Cienega phase pit structure at the San Agustin Mission locus of the Clearwater site has a fired central storage pit. The house and pit are cut through the center by an exploratory backhoe trench (photo by Greg Whitney).

Michael Diehl, Desert Archaeology’s paleoethnobotanist, has examined in-ground storage and suggests that it was a temporary solution, perhaps storing food products for up to a month. The longer a basket full of maize or other food was left inside a storage pit, the more likely it was to be damaged by moisture, mold, insects, and rodents. Most Early Agricultural period sites excavated to date in the Tucson Basin have been in the Santa Cruz River floodplain, which had a high water table and periodically flooded, so in-ground storage was not an optimal situation. The placement of pits inside structures may have helped reduce moisture damage, but also served to guard the stored items from pilfering by people outside of the household.

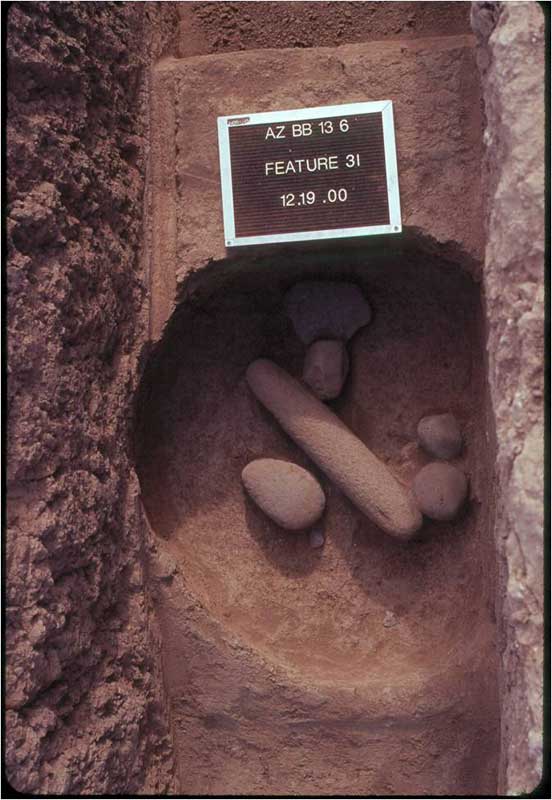

Theft was probably a concern during the time when the village was abandoned during hunting and gathering seasons. Anyone could search through the temporarily abandoned village and take away tools. In response, people sometimes hid valued objects outside of their houses. Excavations at the San Agustín Mission locus of the Clearwater site uncovered a bell-shaped (wider at the bottom than at the opening) pit with a cache of ground stone artifacts. These included a mano, a handstone, two pecking stones, and a large pestle.

Feature 31, an Early Agricultural period bell-shaped pit containing a ground stone cache, San Agustin Mission locus of the Clearwater site, AZ BB:13:6 (ASM) (photo by Allen Denoyer).

Another storage pit at the Las Capas site in northwest Tucson contained a pair of metates, carefully placed next to each other and upside down.

A pair of upside down metates in a storage pit at Las Capas. The edges of the pit were revealed when the backhoe stripped the soil above it; the edges are were marked with white paint to guide the digging when the feature was excavated by hand (photo by Homer Thiel).

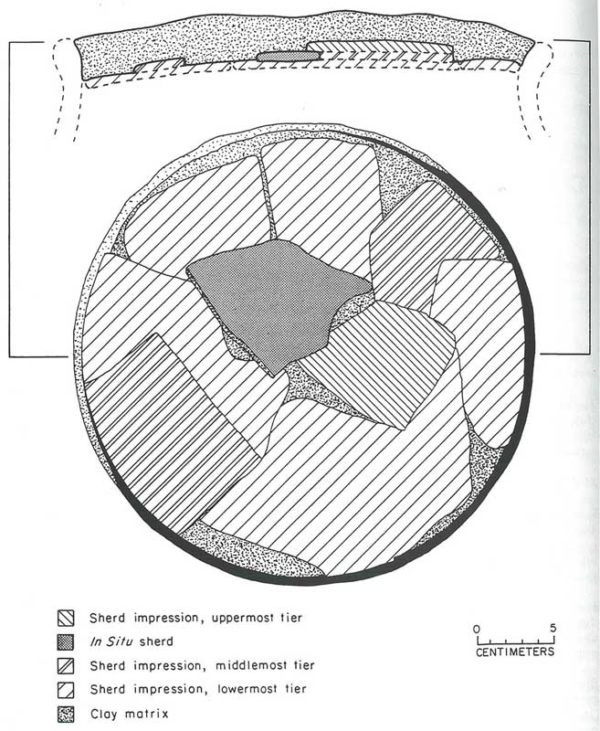

Use of storage pits declined in the Early Ceramic period (AD 50 to 500). The people during this period began to manufacture large storage vessels archaeologists call seed jars. These large, roundish vessels could hold several gallons of maize or other seeds. People sealed the tops of the jars by placing a ring of wet clay around the opening, shaping a broken piece of pottery into a disk, and pushing it down onto the clay. This prevented the usual suspects (water, insects, and rodents) from getting inside and damaging the contents.

Some of the seed jars were kept inside dwellings, but special storage structures were also in use. At the Mission Garden locus of the Clearwater site, we found one such structure, with five broken seed jars taking up most of the available floor space.

Feature 4419, an Early Ceramic period storage structure at the Mission Garden locus of the Clearwater Site (photo by Gregory Whitney).

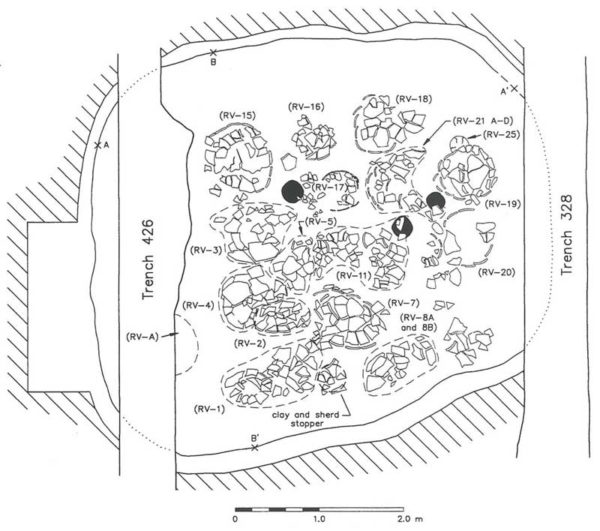

These trends continued into the long Hohokam era. People continued to store things in baskets, leather bags, and pots. Sometimes we can identify the contents of pots if structures burned. At the Los Morteros site, a fire destroyed a structure, designated Feature 3175. A very large amount of pottery was found inside the house and when sorted by the ceramic analyst, at least 25 vessels were present which included a platter, seven bowls, and 17 jars.

Feature 3175 at the Los Morteros site in northwest Tucson contained about 25 reconstructible vessels (marked “RV”) on its floor, many containing burned seeds and cholla buds.

Five of the pots had stoppers. Two of these were made from large sherds. Another was made by placing a mosaic of sherds to completely cover the contents of the jar and then covering the sherds with a layer of clay.

A sherd-and-clay jar stopper found at the Los Morteros site in a storage structure, Feature 3175 (cross-section and view from above).

The fire that destroyed the pithouse carbonized the contents of the jars, preserving them and allowing us to identify them nearly a thousand years later. We found seeds of maize, tansy mustard, blue palo verde, and amaranth, as well as cholla buds.

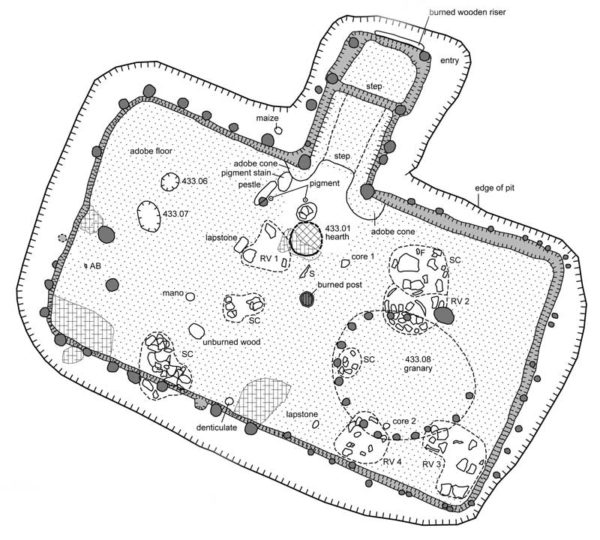

Another method of storage we have found at several sites in the Tucson Basin and elsewhere is the use of granary structures. Excavations at the Yuma Wash site and at AZ AA:12:46 (ASM) at the Pima Animal Care Center in northwest Tucson found structures with circles of post holes in their interiors. The people who lived here set small posts into the floors of their houses, using them to create an elevated platform that probably supported a small domed structure. Elevating the granary floor would have helped keep water, perhaps from summer monsoon storms, from getting the contents of the granary wet. They were most likely used for storing crops. Excavators at AA:12:46 found three smashed plainware jars around the postholes of the granary in pithouse Feature 433. The jars were originally either inside the granary, perhaps falling out as the structure burned, or leaning against its exterior. Intact granaries have been found in openings in cliff faces in other regions of the Southwest. These are basically large upside-down baskets covered in straw and dried mud. Again, they were probably used for short-term storage of crops and gathered foods.

Map and aerial photo of Feature 433 at AZ AA:12:46 (ASM), with the granary on the east (right) side of the floor (photo by Henry Wallace and Robert Ciaccio). The maps shows the locations of the smashed seed jars, along with other artifacts left on the floor of the house.

It is doubtful that the pre-contact people living in southern Arizona had the storage problems experienced by the people of today. They did not accumulate the large quantities of possessions that require numerous closets, garages, and specialized storage facilities that modern Tucsonans use. Archaeological fieldwork has revealed that pre-contact people used storage containers and structures for the short-term preservation of food and seeds, and to keep certain possessions safe when they were away from their settlements. It is somewhat ironic that today museums are faced with their own storage problems due to the large collections made by archaeological projects.

Resources

Desert Archaeology’s Rob Ciaccio produces a variety of archaeological reconstructions.