What Happened to Ventura Robledo?

Jim Vint recently completed a survey on historic ranchland north of Arivaca, Arizona. His background research led first to Ventura Robledo, and then to discrepancies between newspaper stories and a coroner’s inquest. Either way, Robledo met a tragic end.

Miguel Moreno has a Ranch House out buildings & corrals in Sec. 17; he has built a large dam of lime and rock to catch water in the rainy season. Ventura Robledos [sic] has a ranch house, outbuildings and corrals in Sec. 30, both of these men are engaged in stock raising.

I came across this description in George J. Roskruge’s field notes for the General Land Office (GLO) subdivisional survey of Township 20 South Range 10 East, Gila and Salt River Baseline and Meridian, while performing background research for a survey Desert Archaeology recently conducted for Pima County. Our survey project was on the Rancho Seco, located several miles north of Arivaca, and focused on the area along Las Guijas Wash. Rancho Seco is one of several operating ranches managed by Pima County as part of the Sonoran Desert Conservation Plan. Ranching has been central to the area’s economy for nearly 150 years, and the County is furthering sustainable rangeland practices that enhance conservation and preservation of both natural and cultural resources.

GLO plat maps contain a wealth of historical information, like the location of historic roads, homesteads, place names, and so forth. Summaries of each surveyed township identified the economic potential of federally owned land, and focused on agricultural, mining, stock raising resources—as well as wood and timber needed for railroads. George Roskruge surveyed this Township in 1886, when he was a Deputy Surveyor for the GLO.

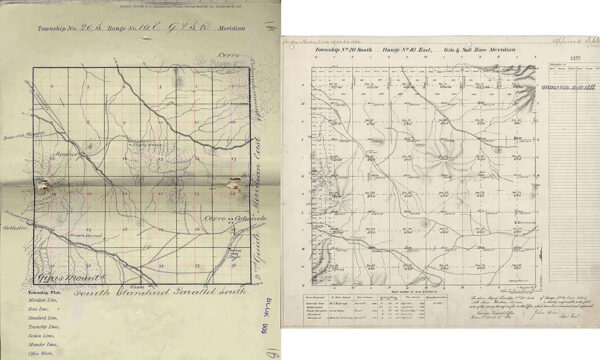

Plat maps of Township 20 South Range 10 East, Gila and Salt River Baseline and Meridian. The sketch map on the left was drawn by George Roskruge and is in his field notebook that documents the subdivision of the township into sections. The map on the right is the official GLO plat. Note the differences between the hand-drawn map and lithograph print in depiction of roads and other features. Transcription of the drawn map to the lithograph stone introduced changes due to the space available on the printing surface, the artist’s accuracy in copying details from the original, and possibly revisions made by Roskruge.

He was attentive to development in the region and was himself involved in mining claims and other property ventures, some doubtless conceived while he was conducting these surveys. In this case he identified two ranchers and their operations by name among his other observations.

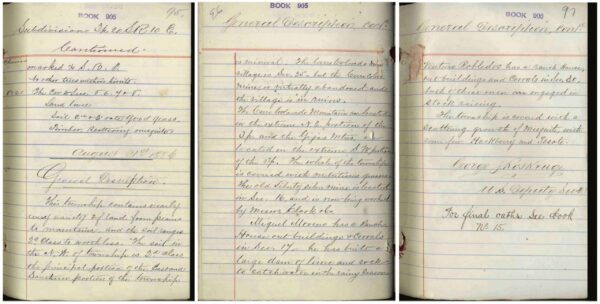

George Roskruge’s general description of T20S R10E, recorded in his field notes for the subdivisional survey. The GLO required a general description of each subdivided Township that provided information on the physical characteristics and economic potential of the land. This was intended for evaluating things like available fuel (wood) for railroads, the potential for mining, agriculture, and stock raising, and homestead opportunities.

I wondered who these men were, and so decided to go looking for Ventura Robledo.

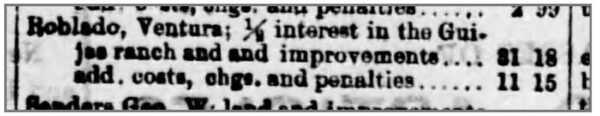

Ventura Robledo’s delinquent 1885 property taxes, penalty fees, and surcharges, published in the December 4, 1886 Arizona Daily Star.

If he merited notice in Roskruge’s maps and notes, where else might he appear? I turned to immigration, census, and other government records, local newspapers, and genealogical sources to see what could be learned. A surprising amount of information was out there. The various bits and pieces put together tell a story of his time in the Las Guijas area north of Arivaca.

Ventura Robledo was born in July 1862, in an unknown town in Coahuila, Mexico. His family immigrated to the United States in 1865, but initially where is unknown. The earliest mention of Ventura in Pima County I found was in 1884, in property tax valuations printed in the August 1, 1884, edition of El Frontizero newspaper. He was a rancher, and held property valued between $1,160 and $1,660 at the time ($37,321-$53,408 in October 2024 dollars). The property type is not listed but presumably was livestock and improvements like corrals and other outbuildings.

By 1885, Robledo held ½ interest in a ranch located on Las Guijas Wash. Public land in Territorial Arizona was under federal ownership, and Robledo and his partner were taking advantage of fee-free open range grazing. He had built his ranch house, outbuildings, and corrals, but had not filed a homestead claim. His fortunes must have taken a downward turn after the “Panic of 1884,” in the midst of the Depression of 1882–1885. Another blow was dealt by a severe drought in 1885 that decimated rangeland conditions in the greater Altar Valley area. Forage was sparse and many of the shallow windmill-driven wells and stock tanks dried up, leaving cattle and other livestock to be culled or moved elsewhere. Robledo was among a long list of individuals delinquent on property taxes for 1885 and whose assets were put up for auction by Pima County to recoup the revenue.

Assessed taxes were $31.18, and he was charged an additional $11.15 in penalties and costs for a total lien of $42.33 ($1,420 in October 2024 dollars). No one purchased the assets, and by default Pima County acquired them.

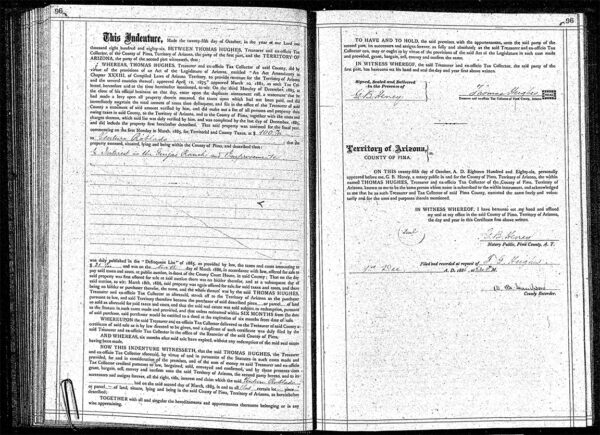

Pima County deed of indenture acquiring Ventura Robledo’s ½ interest in the Guijas Ranch as penalty for delinquent property taxes. Recorded in the Pima County Deeds to Real Estate, Book 19, page 96.

Ventura continued living and ranching at Las Guijas despite this setback.

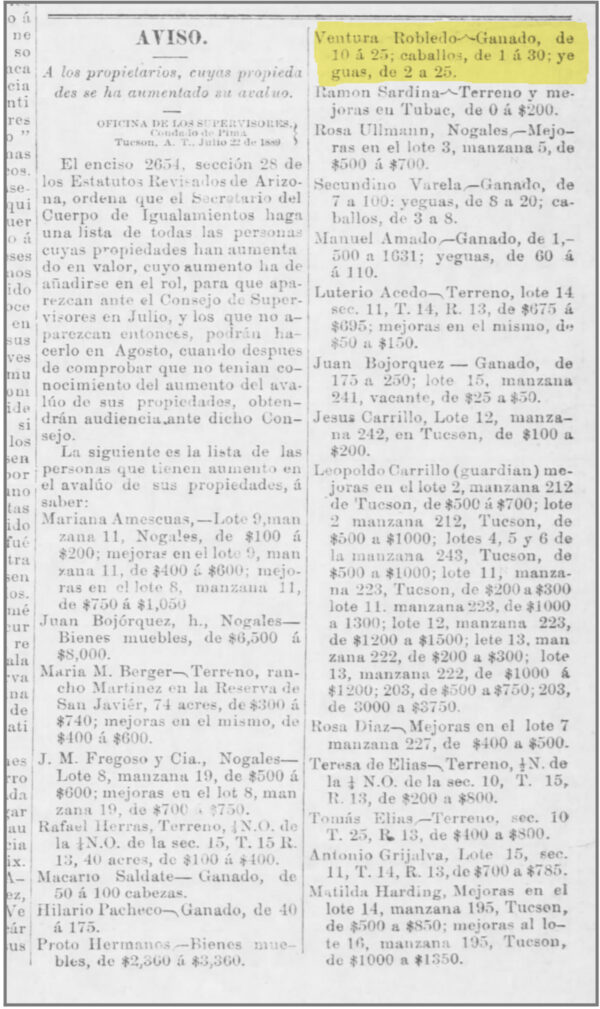

Roskruge deliberately noted Robledo’s and Moreno’s ranches in the area in his 1886 survey notes, which I take as an indication of the visibility of these individuals in the local community, and perhaps also an attempt to portray resilience to the economic situation of the time. By mid-1889, Ventura had reestablished his livestock holdings. Tax valuations reported that his cattle increased over the previous year from 10 to 25, horses from 1 to 30, and mares from 2 to 35.

Pima County published the property valuations for individuals whose holdings had increased from the previous year in order to allow people to protest any increases they felt were inaccurate. This list was published in the July 27 edition of the El Frontizero Spanish language newspaper; it also was published in English in the Arizona Daily Star.

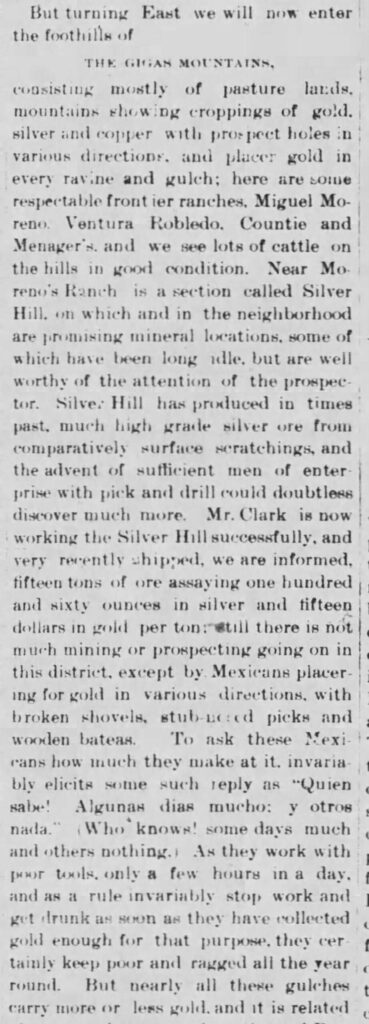

The Arizona Daily Citizen published a special issue on January 1, 1890, that focused on Pima County’s abundant resources, extolling the county’s potential for recovery following the hard times of the depression. It was a propaganda issue intended to bolster people’s morale coming out of the grim era that crushed the prosperity of the boom years that had been fueled by mining and arrival of the railroad. The Arivaca area was described in glowing terms, and Ventura Robledo, Miguel Moreno, Henry Menager, and J. Conti were highlighted as examples of success in the Las Guijas district. They were noted as having “respectable frontier ranches,” and that there were “lots of cattle on the hills in good condition.”

The January 1, 1890, Arizona Daily Citizen special issue on Pima County described the Las Guijas district as a vibrant ranching and mining area. It highlighted the successful ranches of Robledo and others. It also dangled the prospect of gold and other ores yet to be mined in spite of the collapse of intensive gold mining in the area by about 1880; prospecting for lode deposits was being replaced by chasing placer deposits. Note the demeaning portrayal of the Mexican miners. The area was included in BLM brochures on mining as having productive placer deposits well into the 1980s. The newspaper printed another special issue with nearly verbatim prose on January 1, 1895.

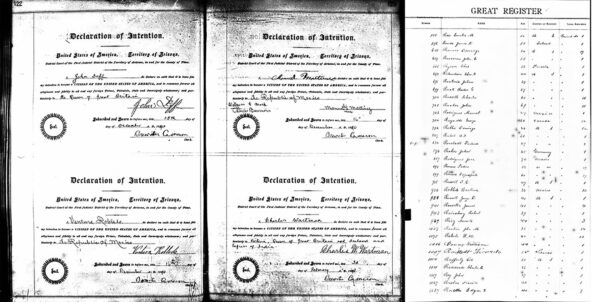

Robledo filed his declaration of intent for naturalization on December 16, 1890, with the Territory of Arizona. I could not find the complete naturalization papers in digitized form. He participated in the “Great American Experiment,” as shown by his voter registration in 1896, the U.S. presidential election year that put William McKinley in office.

Ventura Robledo gained his American Citizenship through application with the Territory of Arizona in 1890. His declaration of intention and renouncement of fealty to the Republic of Mexico was recorded on pages that included another Mexican and two British immigrants. He registered to vote the same year. His name is spelled as “Bentura Robledo,” a common substitution of the letter “b” for “v”, which are homophones in Spanish. Other registered voters include members of the Ronstadt clan, individuals originally from Prussia, Ireland, Canada, Germany, and Mexico. (Sources: Declaration of Intention: Arizona District Court Index to Naturalization Records, 1864-1911; Voter registration: Stewart Family Tree, https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/90427343/person/77015321621/gallery?galleryPage=1&tab=0&sort=-created. Both documents retrieved from Ancestry.com October, 2024).

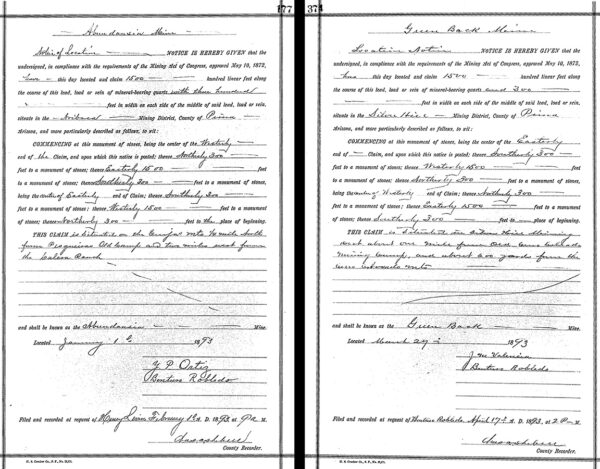

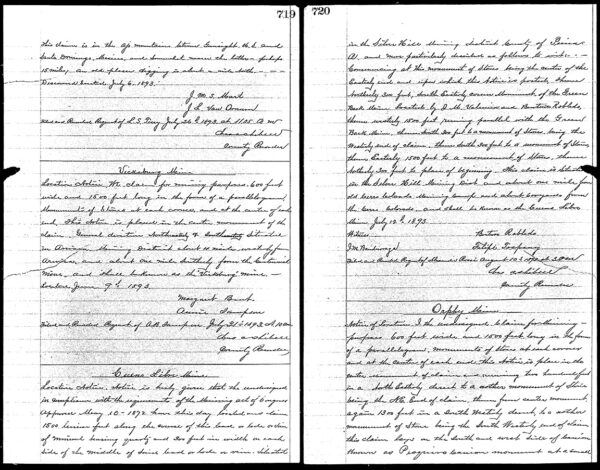

In 1893, Robledo and several colleagues filed three mining claims, a common long-shot practice of economic diversification by ranchers and homesteaders. They named these the Abundansia, Bueno Libre, and Green Back claims

Mine claims required only a general description of their location. Some prospectors were quite specific, while others were quite vague, likely intentionally so. Before the area was formally surveyed and platted with the Jeffersonian Township and Range grid system, metes and bounds were used, along with reference to other claims, physical features, ranches, and other local landmarks. The claim papers posted on the witness stake and on file in the Pima County Recorder’s office provided final proof of ownership. (Sources: Abundansia claim: Pima County Record of Mines Book DD, p. 177; Green Back claim: Pima County Record of Mines Book DD, p. 374; Bueno Libre claim: Pima County Record of Mines Book X, pp. 719-720. Documents accessed online via the Pima County Recorders Office Historical Index, https://pimacountyaz-web.tylerhost.net/web/historicalIndex/HISTORICAL_INDEX3S1, October, 2024).

Based on the description for the Abundansia claim, the lode was located about in the south-central portion of Section 32, about 2 miles southeast of Robledo’s ranch. The other two claims, the Bueno Libre and Green Back, were adjacent to each other and northwest of the old Cerro Colorado mine, about 5.5 miles east of the ranch.

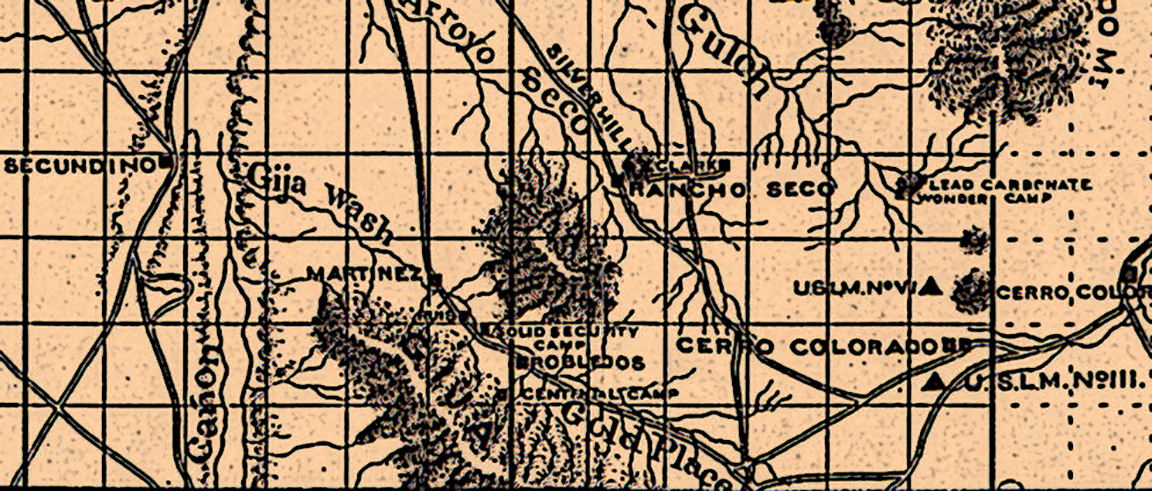

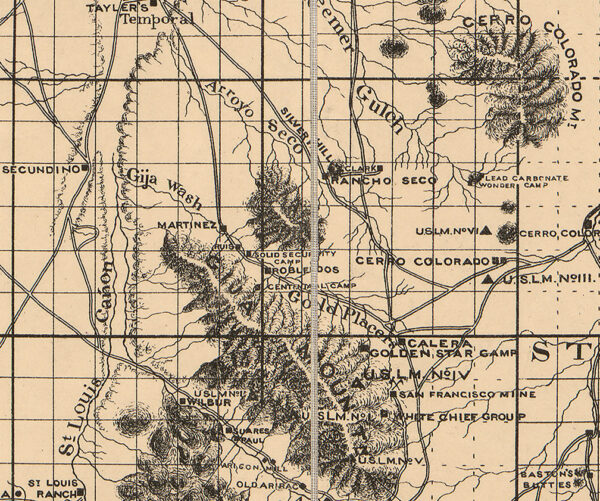

The hopeful spirit of the names given to the claims was probably met with disappointment. The notorious Cerro Colorado Mine had played out by the end of the 1870s, but the hope of Manifest Destiny persisted: the 1890 Tucson Citizen article mentioned earlier described the Las Guijas area as having “… mountains showing croppings of gold, silver and copper, with prospect holes in various directions, and placer gold in every ravine and gulch” and that the Silver Hill area, near Miguel Moreno’s ranch, had many “… promising mineral locations, some of which have long been idle, but are well worthy of the attention of the prospector.” There is no record of whether Robledo and colleagues ever worked their claims in pursuit of this chimerical opportunity. Ventura’s ranch was plotted on the 1893 map of Pima County drafted by Roskruge, but Moreno’s is not. Only major mines are shown, but the Las Guijas Wash is prominently labeled with “Gold Placers” in large print.

This detail of the Las Guijas area is from the official map of Pima County drafted by George Roskruge in 1893. It was compiled from GLO and other surveys. Note that the location of Miguel Moreno’s ranch was now called Rancho Seco. The name has persisted through time to today. Ventura Robledo’s house is shown along with several mining camps and ranches. The “Solid Security Camp” is in the vicinity of the Las Guijas Miine camp. (Map source: Library of Congress web site, https://loc.gov/item/77692954, accessed October, 2024)

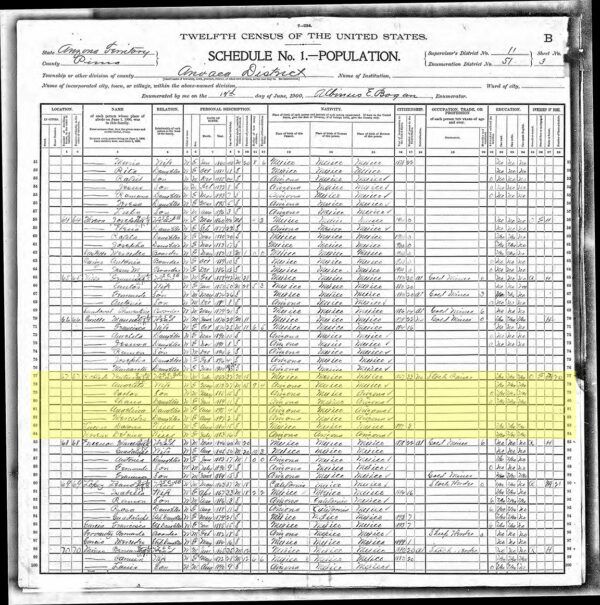

The 1900 United States Census shows the Robledo household with eight family members: Ventura (then 33 years old), his wife Angelita (née Ruiz, 27 yrs), son Carlos (15 yrs), daughters Concepcion (“Chona,” 11 yrs), Angelina (“Lena,” 4 yrs), Mercedes (2 yrs), and two nieces, Dolores Lucero (15 yrs) and Delfina Moreno (16 yrs).

The Twelfth Census of the United States was conducted in 1900. Each census collected different kinds demographic data, which changed (and continue to change) from decade to decade depending on political, macro-economic, and historical reasons.

The census lists Ventura’s occupation as a stock raiser, that he was a naturalized citizen, and that he owned his house free of mortgage. By all appearances he was doing very well.

The Las Guijas area included multiple ranches and several mining camps. One of these was the sizeable Las Guijas Mine camp, located about 1 mile northwest of Robledo’s house, downstream the Las Guijas Wash following the road leading into the Altar Valley. These dispersed places formed the core of the local community, and people regularly visited each other, helped with labor, and gathered for celebrations of various sorts.

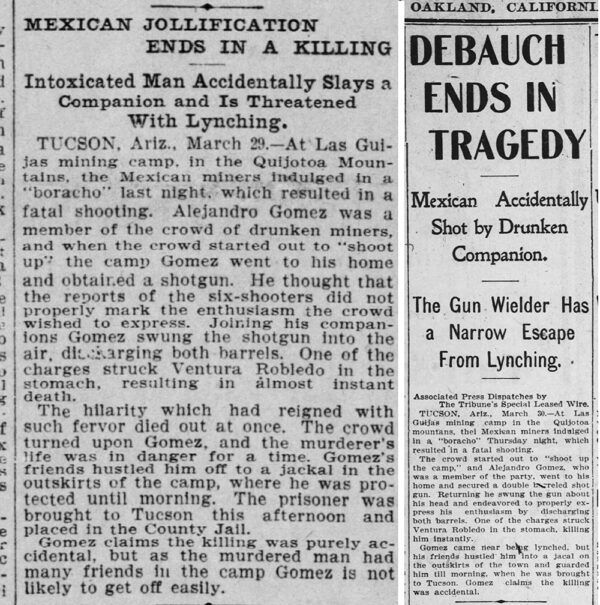

Ventura Robledo was killed by Alejandro Gomez on the night of Thursday, March 28, 1901. According to newspaper accounts published in several San Francisco Bay area newspapers, Robledo was at a “borracho” held at the Las Guijas Mine camp. The articles described a drinking party with stereotypical caricatures we see portrayed in novels and film, with men firing revolvers and other guns in drunken revelry. In these accounts, Gomez retrieved his shotgun to add to the pandemonium and shot Robledo in the stomach when he carelessly fired both barrels, instantly killing him. Several comrades saved Gomez from being killed by Robledo’s angry friends and held him prisoner until morning, when he was taken to Tucson to face the consequences.

The Oakland Tribune and San Francisco Call and Post were among the San Francisco Bay area papers that published articles sent by wire from Tucson about Ventura Robledo’s untimely death. The Tribune’s headline grabbed the reader with bold faced print about the fatal debauch, while the Call and Post’s header was less exaggerated in its choice of words. The Victorian fascination with the wild west is clear in the (slightly purple) prose. Each paper had slightly different edited versions of the story. Note that the Las Guijas Mountains are mistakenly called the Quijotoa Mountains, another mining district in the area 60 miles to the northwest in the Tohono O’odham Nation (Sources: “Debauch Ends in Tragedy”: Oakland Tribune, March 30, 1901, p. 1; “Mexican Jollification ends in a Killing”: San Francisco Call and Post, March 30, 1901, p. 3)

This story was dispatched to the Bay area papers by telegraph wire—the time- and distance-erasing electronic medium of the day—but inexplicably received little play in the Tucson press.

Perhaps this was because the event differed in reality? Homer Thiel, Desert Archaeology’s historical archaeologist and keeper of 19th century Arizona arcana, has transcribed many of the Pima County Coroner’s inquests that are on file at the Arizona Historical Society. One of these is the inquest into Ventura Robledo’s death. The inquest presents a more sober reconstruction of the accident. Rather than a borracho at the mining camp, the shooting happened at Robledo’s ranch house. In this report based on witness interviews, only three shots were fired: one by Ventura using a carbine, and two by Gomez from his revolver, the second of which was the fatal shot. In this telling, there was no drunken party and no animus, only shock and grief over Ventura’s accidental death. The differences in presentation may be any combination of the clinical nature of the coroner’s investigation, the fact it was a careless accident, a desire to minimize gossip and local tensions, and an exaggerated retelling by a reporter enhanced by newspaper editors for an audience in California. We are left with a short 19th century Western version of Rashomon.

The judicial fate of Gomez is unknown. Ventura Robledo is buried in the Arivaca cemetery.

Ventura Robledo and his son Carlos are interred together in the Arivaca Cemetery, with Carlos lain at Ventura’s feet. Que En Paz Descansen. Many families interred in this small cemetery are mentioned in the Tucson area newspapers for various reasons—business, social, and legal—and can be found in the Pima County Book of Mines records and GLO land patents, among other records. Most members of the Montaño family, after whom the Montaño Ranch on the Rancho Seco is named, rest here. (Photographs by James Vint)

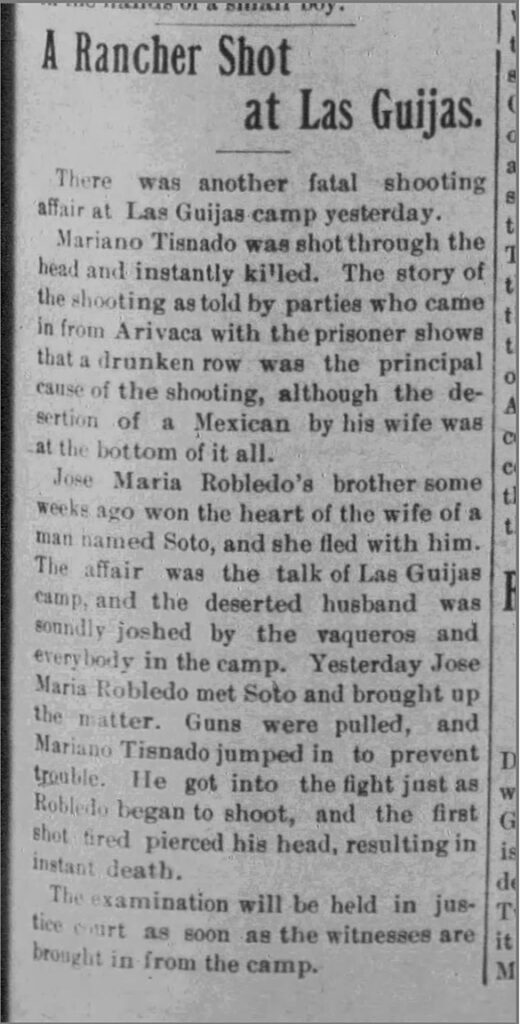

An article in the Tucson Citizen adds yet another twist to this story, if I am making the correct association. On May 5,1901, there was another alcohol-fueled death in the Las Guijas mining camp. Mariano Tisnado, a long-time rancher in the Altar Valley, was killed when he tried to break up a fight between Jose Maria Robledo and a man identified only by his surname, Soto. The article reported that Jose Robledo’s brother (not named, but likely Ventura?) several weeks prior had charmed Soto’s wife at a party and the two absconded away together. Robledo brought up the affair when the inebriated men confronted each other and raised Soto’s fury, and the men drew their guns. Tisnado stepped in to break up the fight just as Robledo fired his revolver and was shot in the head. I couldn’t find any further information on this feud and its judicial resolution.

A family tree found on Ancestry.com includes the lineage of Ventura Robledo, traced through the marriage of his youngest daughter Mercedes, but the information is somewhat incomplete. It shows Ventura having a brother with the name Jose Robledo y Nieble, but no birth or death dates. Their paternal grandmother’s name was Maria Nieble y Robledo. I could not find Jose in any other easily accessed documents, and cannot confirm he indeed was Ventura’s brother, but it seems likely given the tradition of compound matrilineal family surnames.

The epilogue is that Angela successfully continued to operate the ranch after Ventura’s death. She ran her own livestock with the help of son Carlos until his accidental death in 1909. In 1911 she applied for and was awarded a homestead patent on the land where their ranch was located, and afterward leased it out for grazing. She and her daughters subsequently moved to Tucson, and in February 1913 Angela sold the ranch to California oil baron and strict prohibitionist Theodore H. Minor for $2,500 ($80,434 in October 2024 dollars). Much more can be written about Angela and her daughters, but those are different stories.

Angela Robledo continued successful operation of the Las Guijas ranch after Ventura’s death. Her name was misspelled “Angelo” on the GLO patent, and all subsequent documents related to it have this error. She split time living between the ranch and Tucson, where she had enrolled her daughters in school. She ran her own livestock for many years, eventually leasing the ranch and finally selling it for a considerable profit; most homesteaders probably made more money from selling their land to investors and larger stock operations than from their own efforts at ranching or farming. She used the proceeds to invest in real estate in Tucson, where she and her daughters moved to establish a better life. Angela died in 1915, and is buried in Holy Hope Cemetery. (Sources: “New Cattle Company Leases Headquarters”: Tucson Citizen, January 19, 1912, p. 8; “Bargain and Sale Deed”: Pima County Deeds to Real Estate, Deed Book 54, p. 466, accessed on the Pima County Recorder’s Office web site, https://pimacountyaz-web.tylerhost.net/web/historicalIndex/HISTORICAL_INDEX3S1, October, 2024)

Pima County-sponsored historical and archaeological research plays a significant role in documenting the region’s history. It spans the present day to as far back as we can chase it at scales from individual life histories to long-term patterns of cultural and historical change. Small projects like this one turn up unexpected narratives, and even if small they are not trivial—they are the heart of the local community. The short story of what happened to Ventura Robledo comes from bits and pieces of news, official documents, and the serendipitous discovery of a family genealogy. Nuggets like these often lead nowhere, but some, like this one, bring to life the people who made a living in 19th century Pima County, Arizona Territory. The social milieu of the of the frontier West in its declining years was as complicated as today’s, filled with stories of opportunity, struggle, failure, and success, driven by people like Ventura Robledo. Future research on the Rancho Seco and elsewhere will continue to add to these stories.

Suggested Reading:

Sayre, Nathan F. 2002. Ranching, Endangered Species, and Urbanization in the Southwest: Species of Capital. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Sheridan, Thomas E. 1992. Los Tucsonenses: The Mexican Community in Tucson, 1854–1941. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Sheridan, Thomas E. 2012. Arizona: A History. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson.