Henry Ransom, an early African-American Resident of Tucson

Homer Thiel recounts what archaeological investigations in Barrio Libre revealed about the life of Henry Ransom.

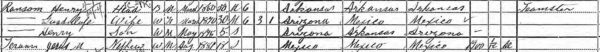

In 1992, Desert Archaeology conducted archaeological testing on City of Tucson Water Department property on South Osborn Avenue, located on the southern half of Historic Block 138 within the Barrio Libre south of downtown. A backhoe was used to strip portions of the project area, locating building foundations, wells, outhouse pits, and trash-filled pits. After fieldwork was completed, documentary research revealed that the occupants of Lot 8 included the family of Henry Ransom, an African-American man who arrived in Tucson in the early 1880s. Henry’s life was briefly told in 1933 when a University of Arizona student, James Walter Yancy, wrote his master’s thesis on African-American residents of Tucson. Other documentary sources helped fill in some of the details of Ransom’s life.

Henry Ransom was born about March 1850 or 1854 in Arkansas, the son of another Henry Ransom. He was likely an enslaved person at birth and would have gained his freedom during the Civil War. The 1860 Slave Schedule for the United States census enumerates 122,563 enslaved persons in Arkansas, but only lists them by age, gender, and race, not name.

In June 1880, Henry was living in Jefferson Township, Davis County, Kansas, working as a farm laborer for James and Mary Maloney.

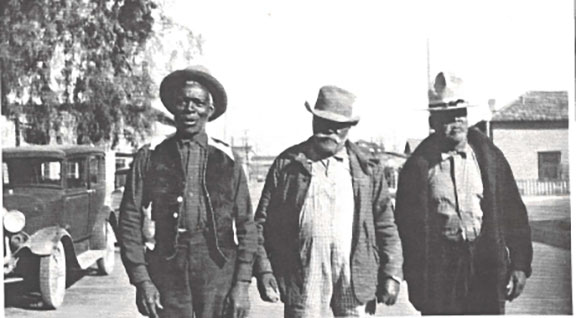

Photograph of “The Last of the 19th Century Negroes” from James Yancy’s 1933 master’s thesis.

Ransom arrived in Tucson shortly thereafter, registering to vote in Pima County in October 1882. He first worked as a freight and ore wagon driver for Jack Boleyn. He then went to work at various hotels—as a cook at the Cosmopolitan and as a yardman and porter at the San Xavier, which was located at the train station. While there he transplanted cottonwood trees from the Santa Cruz River to the front of the hotel.

In 1892 through 1931 he worked for the Tucson Transfer Company as a driver, hauling freight at first in a horse-drawn wagon, and then later using a truck.

Around 1893 Henry entered into a relationship with Guadalupe Ramirez. She had been born in Mexico in March 1870 and came to the United States in 1892. The couple had three children, but only one, Henry Jr., born in May 1895, survived childhood. By June 1900 the couple, their son, and Guadalupe’s nephew Jesus M. Teran were living on Block 138.

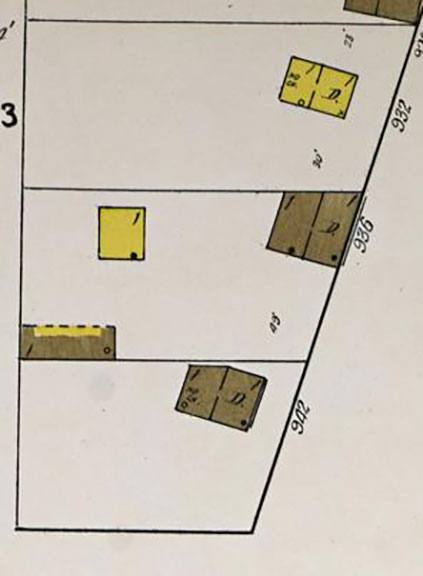

The 1919 Sanborn Fire Insurance map depicts the small Ransom-Ramirez house at 932 South Osborn Avenue.

Because the Territorial Council in 1865 had banned interracial marriage, a law that remained in effect until the 1950s, Henry and Guadalupe could not legally marry. The couple applied for a marriage license in April 1917, but the ceremony did not take place, likely because of the law.

In 1920, the couple, son Henry, and an African-American lodger lived on Osborn Avenue. Henry was a truck driver and son Henry was a laborer at a mine. Guadalupe died in November 1929 at their home from pneumonia. In 1930, Henry and son Henry were living at their home. Henry Sr. retired in 1931 with a pension from Tucson Transfer.

In 1933, Henry was interviewed by James Yancy for his master’s thesis, The Negro of Tucson, Past and Present. This thesis provides valuable insights into the lives of Tucson’s African-American population, both historically and for the 1930s.

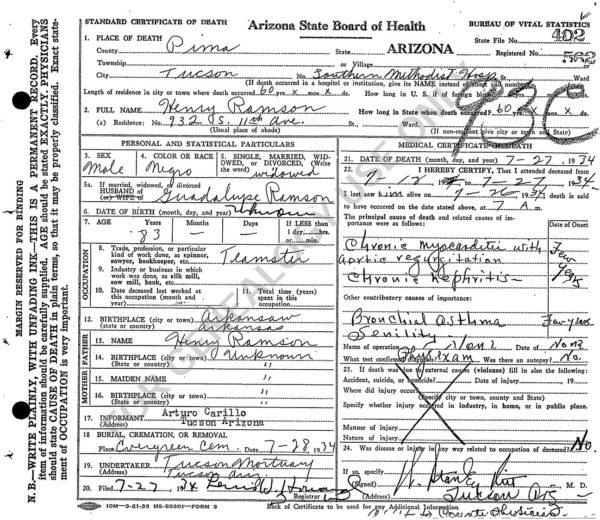

In July of the following year, Henry Ransom died from heart problems at the Southern Methodist Hospital. He and Guadalupe were buried in unmarked graves in Evergreen Cemetery. Their son Henry had suffered from epilepsy and died in 1955 from a cerebral hemorrhage due to a skull fracture after having convulsions.

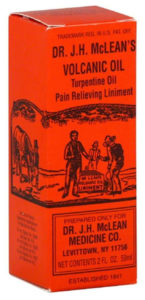

Four decades later, Desert Archaeology used a backhoe to strip a large portion of Lot 8, uncovering many small pit features and collecting a small number of artifacts. These included two glass marbles, a jelly jar tumbler, a pressed glass pitcher, an Umberto brand olive oil bottle, and an earthenware jug. Also found were a Dr. J. H. McLean’s Volcanic Liniment Oil bottle, a popular proprietary medicine used to sooth aching muscles that is still available for purchase today.

Henry Ransom likely used the original version of Dr. J. H. McLean’s Volcanic Oil after a hard day of moving freight. The photo shows the product as currently sold.

No further data recovery took place at the site, and the area is now used as a parking area by the Water Department. Perhaps some day in the future archaeologists will return and excavate the Ransom lot, recovering additional information about their lives.