Home, Sweet Home in the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson

Historical archaeologist Homer Thiel takes us on a home tour of 18th- and 19th-century Presidio households.

Tucson was a Spanish and then Mexican fortress from its establishment in 1775 until the last Mexican soldiers marched away in March 1856. During this 81-year time span, the average population numbered between 400 and 500 Spaniards or Mexicans who lived inside or nearby the walls of the fort, along with perhaps 500 O’odham, Pima, and Gileno (Gila Apache), who resided across the Santa Cruz River at the San Agustín Mission or the Apache settlement a short distance to the northwest of the fort.

So what did the homes of the people who lived within the fort look like? What furniture and possessions could be found inside? An 1820 inventory, two oral histories, and the archaeological record provide answers to these questions.

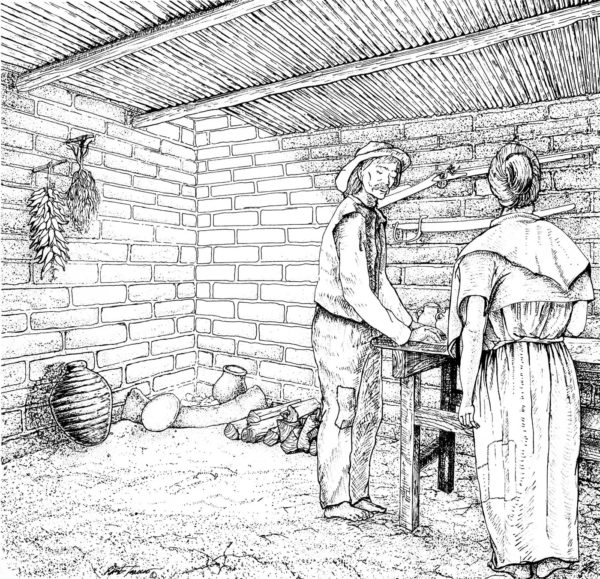

Homes were built from locally available material. Adobe bricks–made from dirt, plant matter, and water –measured about 22 inches long by 11 inches wide and 3 to 4 inches thick. These were formed in wooden molds, sun dried, and then used for walls, held together by a mud mortar. The foundations of houses could be made from rocks collected from the side of Sentinel Peak (now known as A-Mountain), or merely by setting the adobe bricks into a shallow trench. The roof would consist of vigas (beams) made from mesquite, cottonwood, or pine trees, the latter cut from the slopes of nearby mountains. Saguaro-rib latillas (cross-pieces) were laid across the top of the beams and were then in turn covered by a thick layer of tamped earth, sloping slightly to allow rain water to run off through wood or ceramic canales (drain pipes). The floor of homes was simply tamped earth, perhaps covered by woven mats.

Most houses did not have windows, because window glass was an expensive luxury. Francisco Solano León said that the “doors had no panels.” According to Hilario Gallego, “Some of the doors were made of brush and sahuaro sticks, tied together with twigs, or, when the people could afford it, with rawhide. Sometimes the whole door was of rawhide and the windows were made of strings of rawhide.” A fireplace built into the corner of the main room, made with a rounded adobe curb, would heat the room during the winter, when it could also be used for cooking. In the summer, cooking took place outside.

Hornos (bread ovens) were scattered about outside and probably used communally. O’odham cooking vessels were used to made soups and stews, heated by being placed on a trivet of rocks over a small pit where firewood burned. Larger barbeque pits could also be used to roast large pieces of beef.

How were houses furnished? In September 1820, Father Pedro de Arriquibar, who had been the Presidial chaplain since 1797, died. An inventory was created of his estate, which was likely more elaborate than everyone else’s except the Presidio Comandante and his officers. Arriquibar’s house consisted of a parlor, two rooms, a storeroom, and an enclosed backyard. It was furnished with a table, some chairs, and a cot. Personal possessions of a religious nature were a statue of Our Lady of Sorrows, a rosary from Jerusalem, 58 books, and some manuscript sermons. His bedding consisted of a wool mattress, two Pima sheets, a pillow, and a black blanket. His clothing included a Roman cassock, some drawers (underwear), a shirt, some breeches of cotton duck (canvas pants), some hose (stockings), some shoes, and a mantle (cloak). Smaller personal items were a large handkerchief, a large snuff box, a snuff canister, a razor case, two razors, and a hone (sharpening stone). Food preparation, storage, and service items included some glasses, four pottery wine jars, a metal knife, fork, and spoon, and a tin can. He also owned an inkwell and two small bottles, and a candlestick and snuffers.

Francisco Solano León said that houses had “a small table, a few cooking utensils and a roll of bedding.” Most people probably slept on sleeping mats placed on the ground. Gallego stated that Presidio residents made candles out of tallow (beef fat). The cattle bones found at the Presidio and the nearby San Agustín Mission show evidence of being smashed into small pieces, which were then boiled to release the tallow.

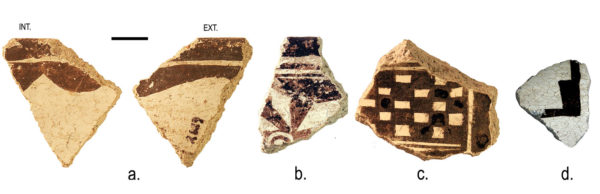

Archaeological excavations within the Presidio have found many items discarded by Presidio residents, but the overall diversity is low. Most common are fragments of Native American cooking vessels: Piman bean pots, large bowls, comal griddles used to make tortillas, and chocolatero pots used to make the morning hot chocolate drink.

A few homes had black-on-white or polychrome vessels manufactured by Hopi, Zuni, or New Mexican Puebloan potters.

The Presidio women served their meals in brightly colored majolica dishes–plates, bowls, and cups. A few Chinese bowls and cups were luxury items that most people could not afford. Beginning in the 1840s, a small number of English transfer-printed dishes became available. Fragments of olive jars, large ceramic amphoras that once held olive oil or wine, are occasionally found. A few pieces of black bottle glass have also been recovered, the bottles once holding alcoholic beverages or medicines.

Gallego described the clothing worn by people: “For clothing most of the men wore nothing but ‘gee-strings’ just like the Indians. Every six months or so the government would send to Hermosillo and bring back manta or unbleached cotton cloth from which men’s trousers and women’s skirts were made. The women wore long skirts and shawls or scarfs. Our shoes were mostly taguas, or rough shoes made of buck skins, and guaraches, which were flat pieces of leather tied to the foot with buck-skin strings which ran between the big toe and the next.”

Most articles of clothing are made from perishable materials (cloth and leather). Among the few clothing artifacts found during our archaeological excavations are plain brass buttons and brass buckles. Some of the buckles are quite ornate, with molded designs, while others are plain and utilitarian.

Documents indicate the Presidio soldiers had to buy a new uniform every year. A few glass beads have been found, as well as a necklace consisting of 44 black glass beads and a religious medal.

Copper wires found in the graves of several children in the Presidial Cemetery once held paper flowers, the crowns placed on the heads of young people to symbolize their innocence. People were generally buried without clothing, wrapped in shrouds held shut by brass pins. Clothing was too valuable to be buried.

Fragments of fine-toothed bone combs have been found. These were manufactured in Europe from cattle bone and were probably quite expensive, albeit useful for removing head lice and their eggs,

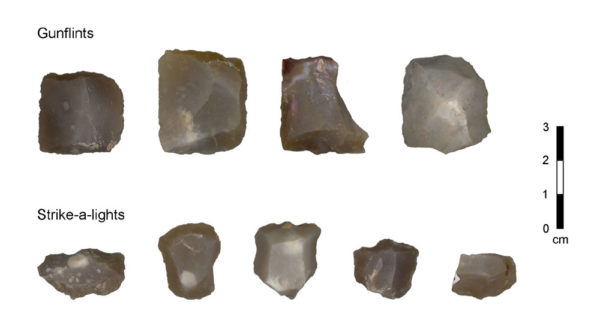

Lead musket balls, gunflints, three trigger guards, and a ramrod holder are the only weapons-related artifacts found to date. The musket balls range in size from 1.3 to 1.6 cm, suggesting they were used for both pistols and muskets. Two of the trigger guards are for Brown Bess muskets manufactured in England. After Mexico gained independence, Spain refused to sell the new government weapons. The Mexican government then turned to England, Spain’s longtime enemy, and they were more than ready to sell muskets to the Mexicans.

At the time, gunflints were manufactured in large quantities in France. As it became more difficult to obtain these, soldiers turned to local stone. They may have asked Native Americans to help flake the stone. As the gunflints wore out, they were repurposed as strike-a-lights, used to create sparks to make fires.

The people living at the Tucson Presidio lived 100 miles from the nearest stores in Arizpe. It was difficult and somewhat dangerous to bring goods from the stores there, so the men and women living in the fort made do with things they could make themselves or acquire through bartering with the local O’odham. Special things–slabs of chocolate, cloth, buttons, beads, and majolica dishes–were imported overland to the fort. These items, necessities and luxuries, helped make life a little easier on the northern frontier of New Spain.

Resources

Historical Address, Having Reference to the Whole Territory but More Particularly to Tucson and Pima County, Arizona Citizen, July 15, 1876 (includes Francisco Solano León’s account of life in early Tucson)

Reminisces of an Arizona Pioneer, Arizona Historical Review, 1926 (Hilario Gallego’s account)