Archaeology Archive: The 1996 Excavations at Historic Blocks 72 and 73, Phoenix, Arizona

Historical archaeologist Homer Thiel opens up the Desert Archaeology archives for a look back at a project in historical downtown Phoenix that touched on public utilities, re-purposing Hohokam infrastructure, and daily household life in the late 1800s.

Plans for a new United States Federal Courthouse in Phoenix led to testing and data recovery by Desert Archaeology in 1996. The project area consisted of two of the original downtown blocks, Blocks 72 and 73. What did we find?

When we arrived, the blocks were covered with asphalt and two small parking structures. Our first step consisted of digging several test trenches in which we found a variety of features. Because these could provide significant information about the prehistory and history of the area, making the blocks eligible for the National Register of Historic Places, archaeological excavations (“data recovery”) were required before the courthouse could be constructed.

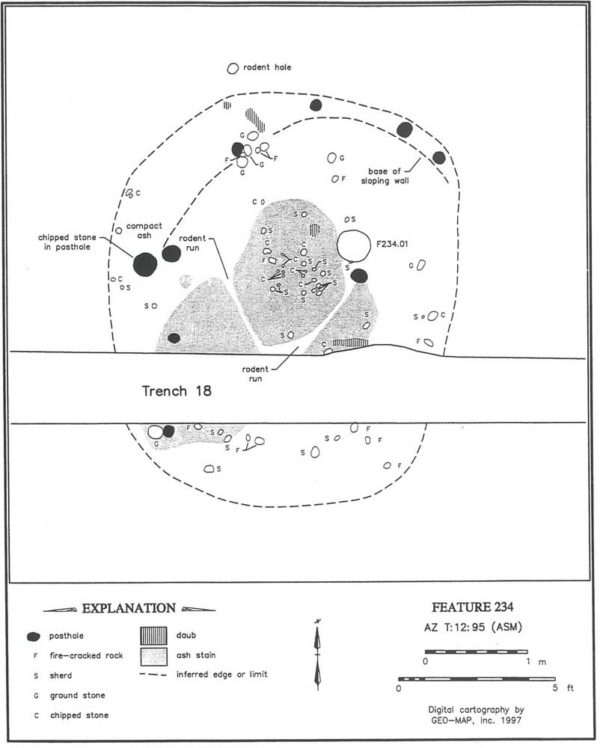

We decided to sample the north half of Block 73, completely stripping away the parking lot and the underlying disturbed soil layer. Once this layer was removed, we found dozens of archaeological features. A test trench in the south half of the block revealed a few more features that we also excavated. The focus of work on Block 72 was more limited, targeting a few important features on its eastern side.

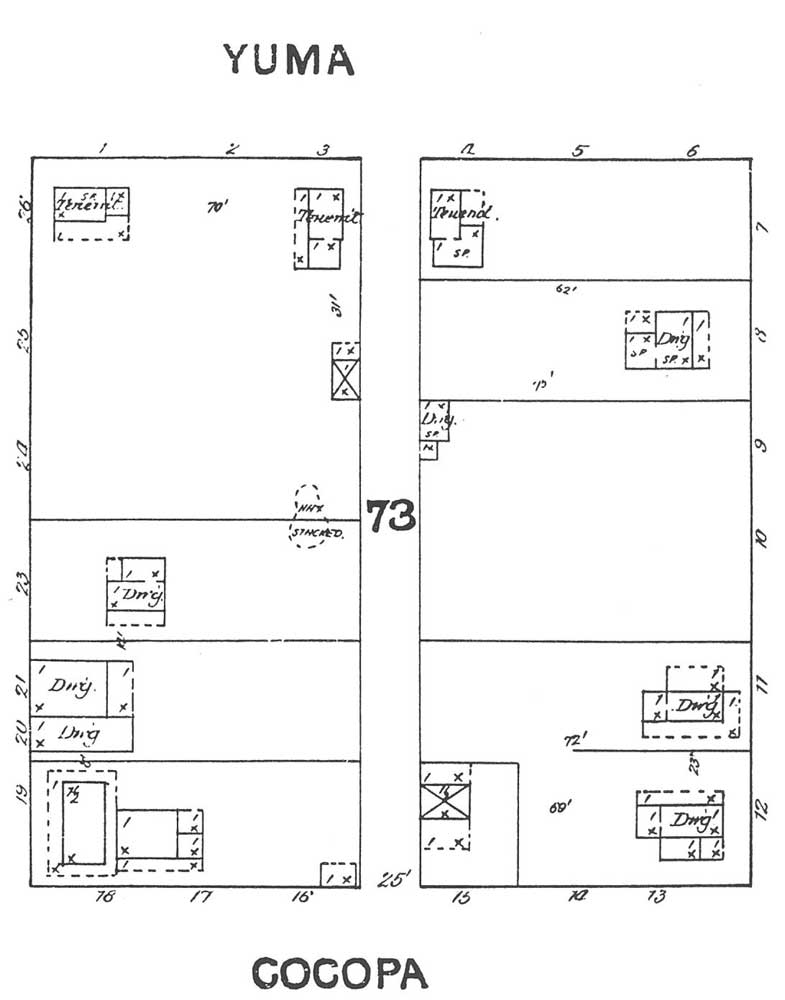

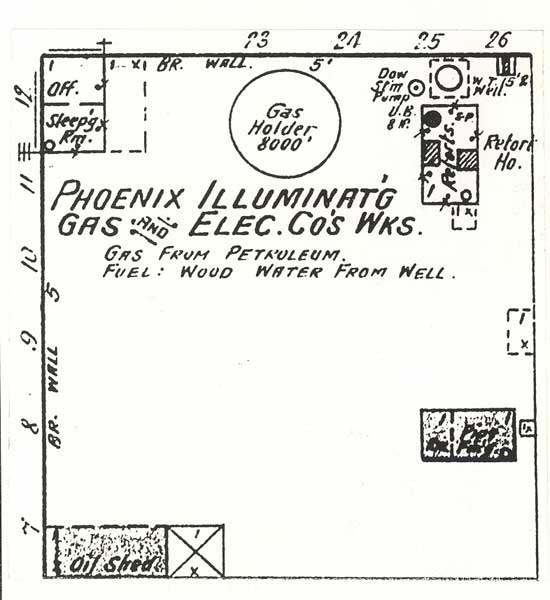

The 1899 Sanborn map of Block 73 (north is on the left side). Yuma Avenue later became 4th Avenue and Cocopa Avenue became 5th Avenue.

The oldest feature documented was a Red Mountain phase pit structure, radiocarbon dated to A.D. 140 to 350. The Red Mountain phase is comparable to the Early Ceramic period in the Tucson Basin. In both areas, this time span saw the first use of large ceramic vessels for storage and cooking. This house was oval, with eight postholes around its perimeter and one next to a floor pit. A layer of ash covered the center of the house, and portions of the floor were oxidized, suggesting it had burned. Scattered across the floor were fragments of three pottery vessels and broken pieces of grinding stones, suggesting that the pit structure was used for trash disposal after it burned. A poorly preserved Hohokam pit structure was also found, damaged by historic period activities.

Jumping forward centuries in time, the U.S. Army established Fort McDowell north of the Salt River in 1865. The military’s need for hay and grain led a group of settlers to re-dig abandoned Hohokam-era irrigation canals for their fields. In 1870 the Phoenix townsite was laid out. Blocks 72 and 73 were close to the western end of the new community. Initially, the blocks were the location of homes. Fire insurance maps are among the documents used to trace changes on the block, showing that multiple businesses opened through time, including a blacksmith shop, a trunk factory, a stone cutting and polishing shop, stores, lodging houses, and, later, auto sales and services. One of the most important businesses was the Phoenix Illuminating Gas and Electric Light Company, which operated on the east side of Block 72 from 1886 to 1899.

A portion of the 1893 Sanborn Fire Insurance map showing the Phoenix Illuminating Gas and Electric Works.

The gasworks was founded by three men from Tombstone, one of whom was an immigrant. Hachiro Onuki was born in 1858 in Japan and came to the United States in 1875, westernizing his name to Hutchlon Ohnick. Although Arizona Territory had a miscegenation law, which prevented people from Asia from marrying people of European origin, Ohnick married Catherine Shannon in 1888 and the couple had four children.

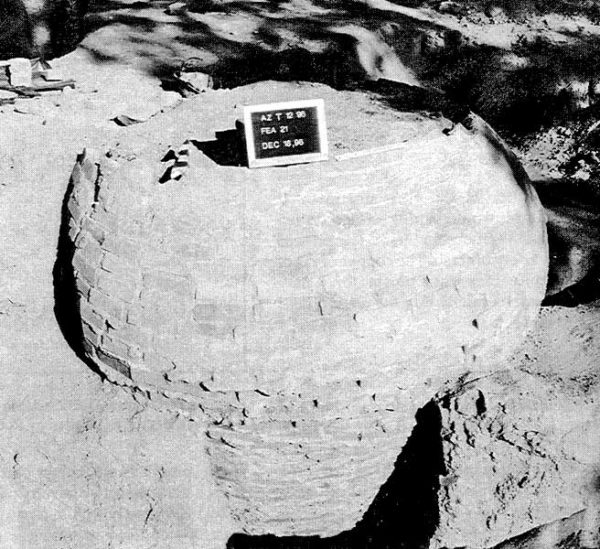

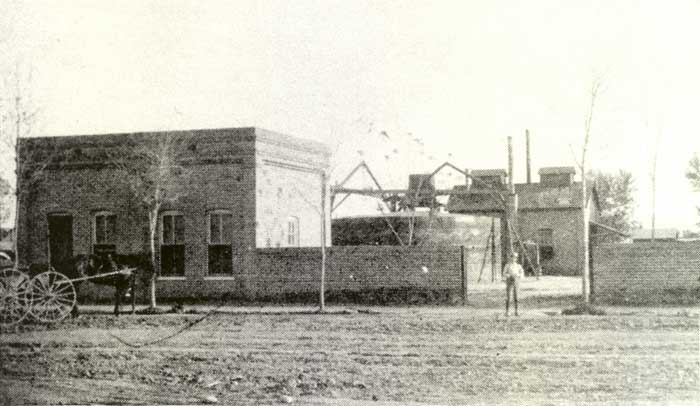

Ohnick supervised the construction of the gasworks, which consisted of a retort building, where wood was burned to heat shipped-in oil. This gave off a gas that was then directed into a large brick storage tank outfitted with a bellows-like contraption.

A photograph of the Phoenix Illuminating Gas and Electric Works, looking south from West Washington Street. An office and dwelling are on the left. The gas holder tank is in the middle, with the retort room behind it (The Sheriff Magazine, December 1955).

At night as gas lights were lit throughout the downtown, the tank lid would slowly compress downward, forcing the gas out into pipes leading to street lights and businesses. The tank was refilled every day. The gasworks began operation in December 1886, and newspapers reported the buildings were “resplendent with bright light.” Residents felt the street and business lighting marked the emergence of Phoenix as a modern city.

The top of the gasholder tank for the Phoenix Illuminating Gas and Electric Works. It was 33 feet in diameter and at least 11 feet deep (photo by Susan Hall).

We excavated 17 outhouse pits and seven wells, and uncovered 10 septic tanks. The wells revealed that the late 1800s water table was about 12 to 14 feet below the historic ground surface. An unstable sand layer forced well diggers to install brick or wood linings to prevent collapse. After city water lines were installed in the early 1900s, the wells were abandoned and filled with trash. We followed OSHA regulations to excavate these deep shaft features, cutting and stepping back the surrounding area to ensure safety.

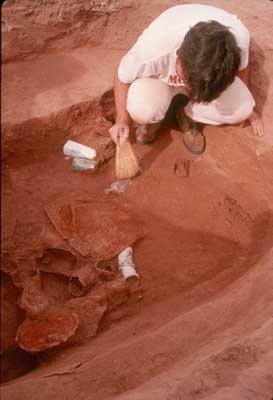

Outhouses (also called privies, waste closets, or latrines) were used as bathrooms in Territorial Phoenix. These facilities had a wooden superstructure over a pit. The pits on Block 72 and 73 ranged in depth from two feet to ten feet, with most between three and four feet deep. Only the deepest one was lined with bricks. Three layers of fill were typically present. At the base was a layer of green loamy soil, mostly decomposed human waste and newspaper pieces used as toilet paper. Small personal items—eyeglasses, combs, and an upper denture—were found in this layer. After an outhouse had been used for a few years, a new pit was dug and the wooden superstructure was moved, and the old hole was used for trash disposal. This second layer usually yielded large amounts of artifacts. The top layer contained material used to finish filling the hole.

An archaeologist uncovers a medicine bottle dropped in an outhouse in the 1890s (photograph by Greg Berg).

Eventually, people switched to using septic tanks. We found several elaborate versions, including one that resembled a giant carrot. An increased concern with hygiene is suggested by the movement of outhouses and septic tanks towards the back of lots through time, away from buildings.

We recovered over 54,000 historic artifacts were recovered, representing about 15,000 items, mostly dating between 1880 and 1915. These included trunk hardware from the Phoenix Trunk Factory and horseshoes from Mayor Frank Moss’s blacksmith shop.

Medicine bottles, dental care items, and medical paraphernalia provided a better understanding of healthcare practices. Other items revealed the contents of parlors.

Toothbrushes and a toothbrush holder from Block 73. In the 1920s, only about 25 percent of Americans regularly brushed their teeth (photo by Greg Berg).

A collection of rocks, stalactites, coral, and shells were tossed into the bottom of an outhouse. Natural history collections were often exhibited in Victorian parlors (photo by Greg Berg).

German and French dolls once played with by Rema and Ruth Dorris, daughters of a middle-class grocer (photo by Greg Berg).

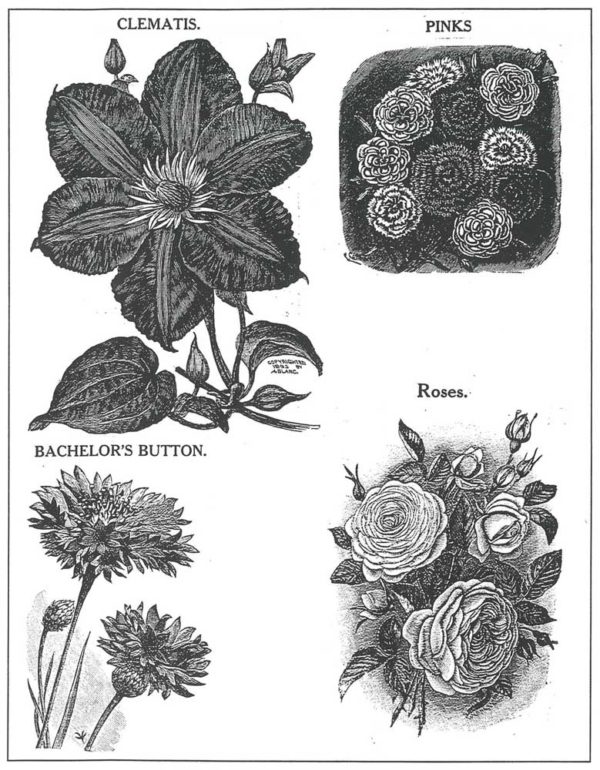

Over 8,000 animal bones and numerous flotation and pollen samples were analyzed. People living on these blocks ate a variety of locally butchered meats, imported seafood, locally grown produce, and bottled and canned goods. Pollen found in samples from the Dorris family outhouse revealed that Mrs. Dorris grew or purchased many kinds of flowers.

The pollen from these types of flowers, from the 1906 Storrs and Harrison Company catalog, were found in the Dorris family outhouse.

After the excavation was completed and the site was cleared for development by Desert Archaeology, the City of Phoenix archaeologist, and the Arizona State Historic Preservation Office, construction began on the Sandra Day O’Connor United States Courthouse. Meanwhile, Desert Archaeology personnel analyzed artifacts and food remains, conducted historical research, and wrote a final report. Copies of the report are available through Archaeology Southwest. The artifacts, photos, and field notes are stored at the Pueblo Grande Museum in Phoenix. The project was funded by the United States government.