Soledad Jacome: Historical Archaeology and a Rediscovered Life

Historical archaeologist Homer Thiel shows how the artifacts we excavate are used to fill in details of lives that are otherwise lost to the passage of time.

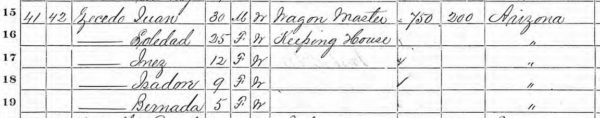

Life in Territorial-era Tucson was often difficult. In 1873, Soledad Jacome’s common-law husband, Juan Siqueiros, disappears from the documentary record. He may have died, or perhaps he is the man by that name who appears on the 1880 census with another family. Soledad was left with four daughters to raise—what happened to her and her family? Documents and archaeology tell the story of this once-forgotten woman.

Soledad was born in the early 1840s somewhere in Mexico, and moved to Arizona Territory sometime prior to 1858. We don’t know who her parents were or where exactly she came from. Her husband Juan was born circa 1840, apparently in Tucson, and was probably the son of a Presidio soldier. In the 1860s, the couple lived in a house in the south part of Tucson, south of modern Broadway Boulevard. Juan worked as a freight wagon driver. Consumer goods (preserved foods, bottled beverages, cloth, buttons, tools, toys, etc.) were carried overland in large wagons from Guaymas, Sonora; San Diego, California; and Santa Fe, New Mexico. Each trip could be dangerous. Horses could run away, wagons could overturn, and occasionally freighters would be killed by Apache warriors. But this was the only way for goods to reach Tucson and the rest of southern Arizona prior to the railroad.

In the mid-1860s, the couple built a house in the north part of town, on what is now Court Avenue. This Sonoran row house has typical design features of that architectural style: adobe brick walls, a flat roof with saguaro ribs laid over beams, with mud packed on top; high ceilings; originally a tamped earthen floor; a corner fireplace; and doors that were opposite each other, allowing air to circulate through. The backyard was a patio area, with a well and privy pits. In the early 1870s, two more rooms were built to the south. The middle room had pieces of freight crates used for the ceiling, some with painted addresses still visible. After the 1880 railroad arrival, milled wood floors were installed.

The 1870 census listing for the Siqueiros-Jacome family. The family’s surname is misspelled, a common occurrence when English speakers encountered Spanish names.

In the mid-1870s, Soledad became a single mother. She had four daughters to support: Inez (b. 1858), Isadora (b. 1860), Bernarda (b. 1865), and Paula (b. 1873). Two other daughters, Phillipa (b. 1862) and Petra (b. 1868), had died as children, the latter during the 1870 smallpox epidemic that killed dozens of children. How was Soledad going to support her family?

Women had few employment opportunities in the last half of the 19th century in Tucson. Most women were keeping house, taking care of their families. For those women who had to earn money to support themselves and family members, the 1870 Federal Census for Tucson lists the following occupations: domestic servant (n=46), farmer (n=3), laundress (n=56), milliner (n=5), retail grocer (n=1), retail merchant (n=1), seamstress (n=131), and Sister of St. Joseph (n=7). In all, 250 of the 858 adult women in Tucson had jobs outside their own domestic duties.

Soledad chose to become a seamstress to provide for her family. Seamstresses could design and sew new clothing, and could repair and re-fashion existing pieces. In the days before sewing machines, most clothing was sewn by hand.

A bone pin holder, brass thimble, and two straight pins (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

In 2005, Desert Archaeology conducted excavations beneath the Jacome-Siqueiros House. We located the original dirt floors below the later milled fir flooring. We discovered that the house had been built over Presidio-era trash, a prehistoric pit structure, and prehistoric storage pits (a topic for another blog entry).

Archaeologist Lisa Gavioli Roach drawing a profile inside the north room of the Siqueiros-Jacome house (photo by Homer Thiel).

In the back yard we found a large soil-mining pit, where people dug dirt to make adobe bricks and mud plaster, afterward filling the hole with trash. We also found several privy pits and a well, separated by a short, unsanitary distance.

Archaeologists Rob Jones, Jeff Charest, and Gaylen Tinsley working on the backyard soil-mining pit (photo by Homer Thiel).

The artifacts and food remains found provide a glimpse of the family’s daily life, information that does not appear in any surviving records.

Most of the dishes recovered in the backyard were plain, inexpensive whiteware vessels. A few decorated dishes were present, perhaps gifts from Soledad’s sewing customers or a rare luxury purchase. She cooked meals in the corner fireplace or perhaps on a small iron stove. It is likely that there was an outdoors hearth in the backyard that left no trace.

A sponge-stamped saucer, transfer-print bowl, and a plain whiteware plate (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

Soledad purchased some prepared foodstuffs. We found tin can fragments, which could have held fruits, vegetables, or soups; as well as bottles for catsup, mustard, olive oil, olives, flavoring extracts, and jellies. One bottle marked EXTRACT OF MALT contained a nutritional supplement given to children. Soledad purchased mostly beef from local butchers, but Desert Archaeology zooarchaeologist Jenny Waters also identified smaller quantities of mutton, pork, and chicken. Ethnobotanist Dr. Michael Diehl identified maize, wheat, apple, apricot, chili peppers, plums, tomatoes, raspberries, mustard, grapes, and walnuts, along with a large number of figs from an outhouse pit. The fig tree in the house patio may be a descendant.

Fragments of glass lamp chimneys, a milk glass lamp globe, and brass burners from kerosene lamps show how the family lit the interior of their house.

An unusual find was a Remington New Model Army .44 revolver, made between 1858 and 1875. Found in the backyard soil mining pit, Soledad may have kept the firearm to protect herself and her daughters.

A Remington New Model Army revolver (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

We found a large number of buttons (n=181) scattered within five pit features in the backyard. Almost three quarters of these were white porcelain/milk glass or shell buttons, typically used for undergarments, men’s shirts, and women’s blouses. Most of the sewing work done by Soledad involved creating or repairing the everyday clothing worn by her neighbors. However, we found a few larger, fancier buttons. Soledad’s daughter Isadora was known for the Mexican wedding dresses she created, a talent probably taught to her by her mother; Isadora may have stocked these buttons for her own work. Sewing goods found included straight pins, safety pins, four thimbles, a ruler, and a bone pin holder. We didn’t find any sewing machine oil bottles or parts, and it is probable that Soledad never had one of those cost-saving but expensive machines.

A variety of buttons (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

Personal artifacts recovered included a small crucifix. Catholic church records reveal that Soledad had each of her daughters baptized at the San Agustín Cathedral. We found combs, perfume bottles, and a ceramic cold cream jar, suggesting the women in the household cared about their appearance.

Two perfume bottles and a ceramic cold cream jar lid (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

We found a number of small, inexpensive dolls, once played with by the young daughters.

Inexpensive ceramic dolls (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

Also recovered were numerous education-related items: ink bottles and jars, slate pencils, and fragments of school slates. Although Soledad was illiterate, she made sure her daughters attended the Catholic girls’ school run by the Sisters of Saint Joseph.

Ink bottles and a slate pencil (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

It was not all work, no play. We found evidence for leisure activities in the back yard, including a number of alcoholic beverage bottles that once held beer, champagne, whiskey, and other hard liquors. Some of these were probably enjoyed by renters occupying the other rooms in the house. At least one Chinese man lived there, as seen by an opium pipe and rice bowl fragments. Several smoking pipes were also found, as well as a cigarette package. It would not be surprising for Soledad to have smoked tobacco.

The medicine bottles recovered suggest some of the health problems endured by the family. They included HAMLIN’S WIZARD OIL, a painkiller that was a combination of alcohol, gum camphor, sassafras oil, myrrh, capsicum, and chloroform. HOSTETTER’S STOMACH BITTERS was used for digestive problems and also contained 44 percent alcohol. A J. W. BULL’S COUGH SYRUP was formulated from a sugar syrup and morphine. The usefulness of these products was probably minimal.

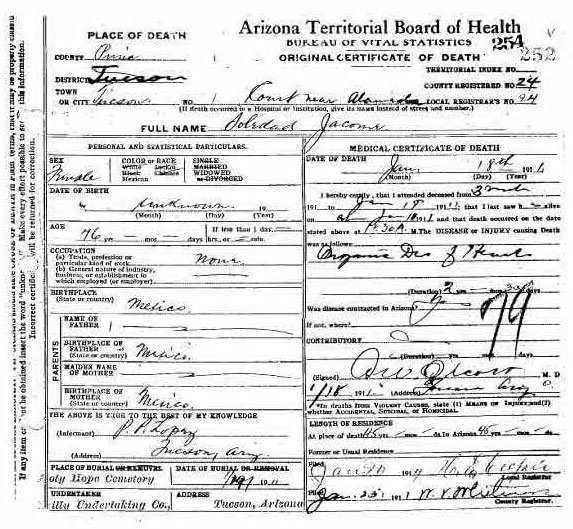

Soledad died in 1911 from heart trouble, in her late 60s or early 70s, having lived in her home for over 50 years. She is buried in an unmarked grave in Holy Hope Cemetery. Two of her daughters had children, and descendants live in Tucson today.

Soledad Jacome’s 1911 death certificate (courtesy az.genealogy.gov)

Resources

The archaeological work described was funded by the City of Tucson. People can visit the Siqueiros-Jacome House at 196 N. Court Avenue Wednesdays through Sundays, 10 AM to 4 PM, and see many of the artifacts illustrated in this blog post at the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson Museum.