Answering Archaeology Questions: How Do Archaeologists Find Sites?

If you follow our Instagram (@desert_archaeology), you’ve seen plenty of photos taken by our survey crews in the wilds of central Arizona. Homer Thiel explains the ins and outs of why we survey and how we use these often strenuous hikes through unforgiving terrain to find sites and understand how human activity is mapped onto a landscape.

How do archaeologists find sites? This is a common question we are asked. Archaeologists working in the southwestern United States use two methods to locate new sites: surveys and test trenching. This blog entry focuses on surveys.

The process starts when someone needs a piece of land examined to see whether sites are present. This information helps government agencies manage lands and plan for the future as they assess priorities for land use. Government agencies at the local, county, state, and federal level are legally required to contract surveys by cultural resources professionals for many reasons. Surveys may be completed prior to road projects, the construction of new buildings, timber sales or fire prevention work, or when Arizona State Trust lands are being sold. In certain places, private land owners also have to undertake surveys—as an example, Pima County, Arizona requires developers to do surveys if more than one acre is to be disturbed by development.

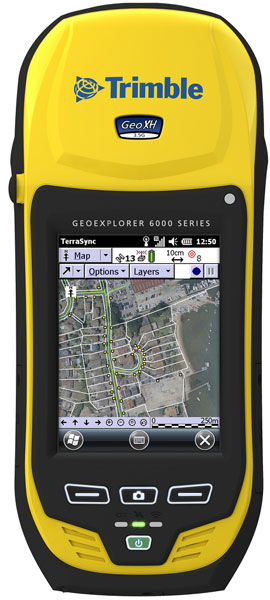

After being chosen to conduct a survey, the archaeological company meets with the client to go over the requirements for the project. Then we conduct background research so that we know what to expect once we hit the ground. Government agencies typically provide information about sites that have already been recorded on the land parcel in question, and archaeologists can also consult the information that is maintained in the Arizona State Museum’s AZSite database. Other government agencies may also maintain site files. Historic maps and databases, such as those created by the Government Land Office and the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in the 19th and 20th centuries, may show the location of historic features, including roads, houses, and fields. Desert Archaeology uploads all of this information onto the tablet devices we take into the field so that it is readily available to the crew. We also head out with USGS topographic maps and survey area boundaries uploaded to our Trimbles—handheld GPS devices we use to orient ourselves on the survey and map the precise locations of cultural materials we find.

The trusty Trimble.

After this preliminary work is completed, it is time to head out into the field. Our crew members walk in parallel transects (straight lines spaced a consistent distance apart, usually 10 to 20 meters) through the project area looking for artifacts and archaeological features. Artifacts can include flakes of chipped stone; finished flaked stone tools such as projectile points and scrapers; ground stone manos and metates; pieces of pottery; bits of sea shell; or historic items made from glass, metal, and ceramics. Prehistoric archaeological features may include foundation stones for structures, rock art panels, and roasting pits, which are visible as areas with fire cracked rocks and charcoal-stained earth. Historic period features could include old road beds, the foundations of cabins, rock cairns for mining claims, or piles of discarded trash. We generally record anything 50 years or older for historic sites. In some cases, archaeologists will move off of the transects to examine particular spots likely to have sites, such as the areas beneath overhanging cliffs, flat spots on the ends of ridges, or land along streams, washes, and rivers.

Tyler Theriot maps a site using a Trimble GPS device. A two-room structure lies beneath the two trees, the outline of foundation rocks barely visible in the photograph.

In the past, archaeologists used toilet paper or pin flags to mark transects. Today, hand-held GPS devices help us stay on course. Sometimes this can be very difficult, especially in areas with catclaw acacia and dense stands of manzanita.

Vegetation can make surveying difficult. Here, Stacy Ryan looks for artifacts amidst a grove of manzanita.

When a crew member spots an artifact or feature, they shout, “Sherd!” or “Point!” or simply “I found something!” The crew stops and begins the painstaking task of looking in the vicinity of where the something was found, marking the locations of additional artifacts with pin flags. In some cases nothing else is found, meaning the item is recorded as an isolated artifact or feature. The crew records the locations and short descriptions of these isolated items and then moves along.

If more items are found, a site may be present, depending on the quantity, density, and diversity of artifacts. The definition of a site varies among the various government agencies. The Arizona State Museum defines a site as being at least 50 years old and having specified combinations of minimum numbers of artifacts and features within an arbitrary area. After examining the ground surface and flagging artifacts and features, if the finds qualify as a site, the crew gets down to the business of recording it. Desert Archaeology uses tablets to efficiently record the data required by the client agency and quickly transmit them back to the server at our Tucson office. Different government agencies have different recording requirements, but the information usually includes a description of the site area, artifact counts, and photographs of the general site area, features, and diagnostic artifacts.

Stacy Ryan counts artifacts in a 1-square-meter unit. The locations of other nearby artifacts are marked by pin flags.

While some crew members enter the data on tablets, another archaeologist maps the site using the Trimble device. The mapping always includes the site boundary, any archaeological features present, the locations of diagnostic artifacts, the location of prominent natural features including washes or large rocks, and the locations of modern disturbances including roads, cattle tanks, and looters’ pits. Small sites might be recorded in half an hour; large, complex sites can require an entire day or more.

Archaeologists and land managers need to know the dates of the sites, their function, and who created and used them in the past. In the field, we look for diagnostic artifacts that will help us make these determinations. Datable artifacts can include projectile points, decorated pottery sherds, and bottles with maker’s marks or product names.

The function of sites can sometimes be identified by examining the full suite of artifacts present on them. A lithic quarry may only have pieces of flaked stone present. A habitation site may have the remnants of structures and a wide variety of artifacts. Historic mining sites may have claim cairns, mining equipment, and dangerous shafts. We also record linear features such as roads and railroad tracks. Much of northern Arizona had telephone lines strung in the early to mid-20th century, and phone companies often used trees for poles. We have to be on the lookout for trees with insulators wired onto them.

The types of artifacts present may also reveal who created the site. The types of ceramics may suggest which pre-contact Native American group utilized the site. For historic period sites, certain artifacts may be linked to a particular ethnic group. The Apache living in central and northern Arizona often modified commercially manufactured artifacts to meet their needs, such as punching holes in cans to create strainers. The Chinese used items that were rarely used by other groups, including porcelain rice bowls, stoneware sauce jugs, and Chinese coins. Basque shepherds in central and northern Arizona created distinctive tree art. Diagnostic artifacts are photographed and described in the field. Many surveys are “non-collection,” meaning that no items are brought back from the field. In other cases, it is a requirement that diagnostics be collected. These are placed in a plastic bag with a label containing locational information.

Diagnostic artifacts at a historic site included a marmalade jar, a whiteware pitcher fragment featuring a corn cob design, a decal-printed dish fragment, and a horseshoe. The decal printed ceramic dates to after 1900. These items and others found at the site indicated it was occupied in the 1910s or 1920s by a family of construction workers.

Once a site has been recorded, the crew members return to their transects and the survey continues. Surveys might be completed in a day or might require months of work, depending on the size of the project area.

After fieldwork has been completed, the effort switches to the office. Mapping specialists create maps from the GPS data that was recorded at the site and feature level. We prepare site cards—the official records of the sites we found—and file them with the appropriate agency, such as the United States Forest Service or the Arizona State Museum. The agencies keep these records into perpetuity so that people making decisions about land use in the future will have an easily accessible reference telling them what cultural resources are present on specific parcels. Finally, we prepare a report that describes the location and environmental setting of the project area, the reason the survey was required, previous cultural resources management work in the area, and the current survey’s methods, results, and recommendations. These reports are then used to determine whether additional measures are needed to preserve or record cultural resources on the land before it is disturbed by development or other work.

Survey work can be difficult—the terrain may include steep slopes, thorny bushes, and streams and rivers that need to be crossed. But the work is rewarding, as new sites are found and previously-known sites are re-documented. The work is an important effort that helps to preserve and manage our country’s cultural resources.