Archaeology Archive: Exploring Fairbank

Homer Thiel takes us on a road trip to Fairbank, Arizona, a ghost town just west of Tombstone, to explore not just the historic records of the town but the Hohokam settlement established in the same place a thousand years earlier.

Back in the 1980s and early 1990s, the Center for Desert Archaeology (today Archaeology Southwest) conducted an intensive survey along the San Pedro River. Volunteers spent hundreds of hours walking on both sides of the river, recording many archaeological sites. One of the sites located on the east side of the San Pedro is the ghost town of Fairbank, today a popular destination for bird watchers and hikers. The Arizona Department of Transportation decided to make improvements on US 83, which runs past Fairbank. In 2002, Dr. Patricia Cook led an archaeological data recovery project for Desert Archaeology that explored both sides of the road. What was found?

Hohokam archaeology

The first phase of fieldwork was to cut backhoe trenches to see what was hidden beneath the ground surface. The trench walls were scraped with hand tools to help identify where features were located and how deep they were. Archaeologists recorded these and other features by drawing profiles and filling out forms.

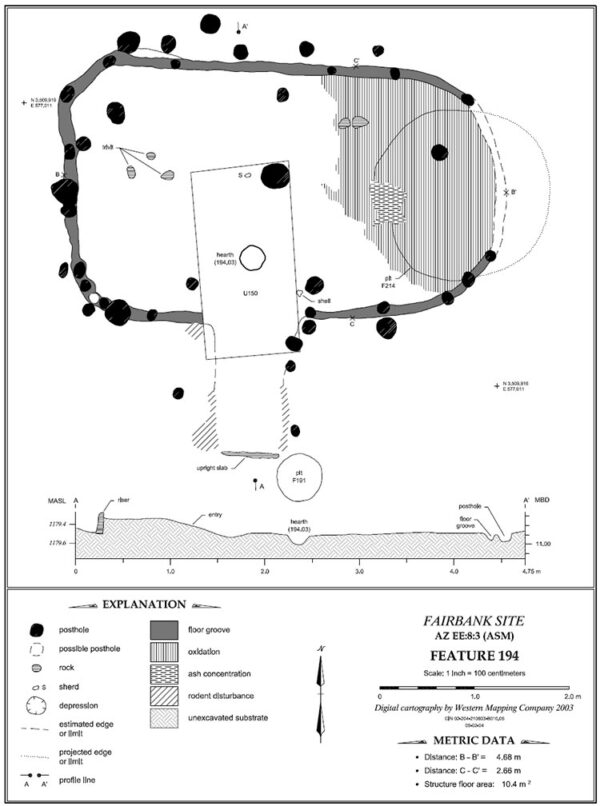

About 20 Hohokam pit structures were identified in trenches, with those on the west side of the road deep enough that they would not be affected by road construction. Eleven structures on the east side were chosen for excavation. Portions of the site were then scraped with a backhoe, revealing many other features.

Three houses were completely excavated, all of them house-in-pits. A house-in-pit has the walls built inside of the foundation pit. Postholes are present along the inside pit edge, sometimes placed in a groove. These were for the walls and roof of the structure. An opening in the groove usually indicates where the entrance of the house was. Many pieces of reeds were found in burned houses, indicating that this material was extensively used to cover the walls and roofs (read more about pithouse architecture here).

The pit structures at Fairbank varied in size and construction details. All were sub-rectangular with rounded corners. Floors were made from adobe plaster or merely tamped earth. Some had plastered fire hearths located inside the entranceway. Some had storage pits cut into the floor.

Other features found included exterior pits used for cooking or storage. Both cremation and inhumation mortuary features were recovered with human remains that were repatriated to the Tohono O’odham Nation.

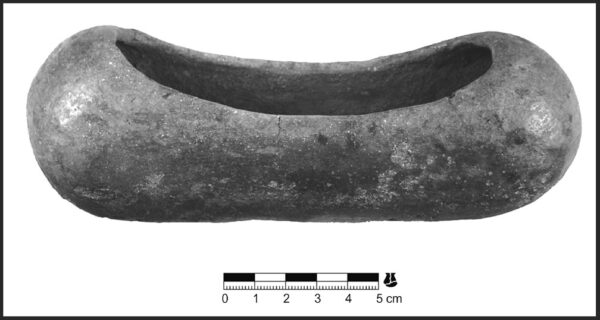

Among the interesting artifacts was a plain ware elongated vessel that looks like a hotdog bun. This vessel type has been found on Hohokam sites elsewhere in southern Arizona. How it was used remains unknown.

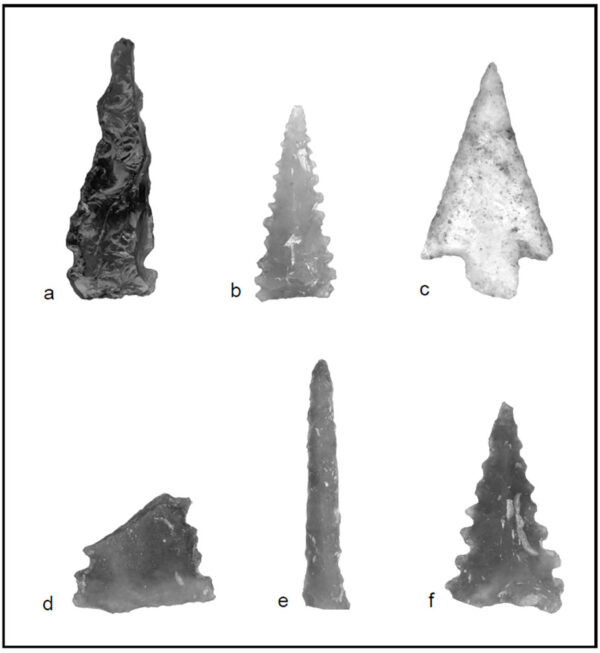

Projectile points and a drill indicate residents hunted and used stone tools for craft activities.

Hohokam projectile points (a-d, f) and a drill (e) recovered from excavated pit structure features at Fairbank.

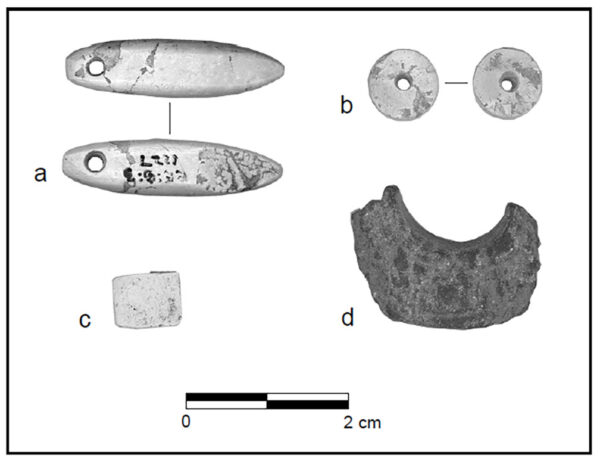

A turquoise pendant, bead, and tessera (mosaic material), and a pyrite ring may have been manufactured at the site. Other ground stone tools found included manos and polishing stones.

Hohokam ground stone ornaments (turquoise pendant, turquoise bead, turquoise tessera, pyrite ring fragment) from Fairbank.

The houses, other pits, and mortuary features indicate that a large, dense settlement was present at Fairbank during the Hohokam Colonial period (AD 750-850). Pottery from earlier and later periods found at the site suggests older and younger structures were present in other areas. Each excavated house had a range of resource procurement tools, with no evidence that a single household specialized in certain crafts. Residents grew maize and squash, with a nearby canal bringing water from the San Pedro River to their fields.

Historic Fairbank

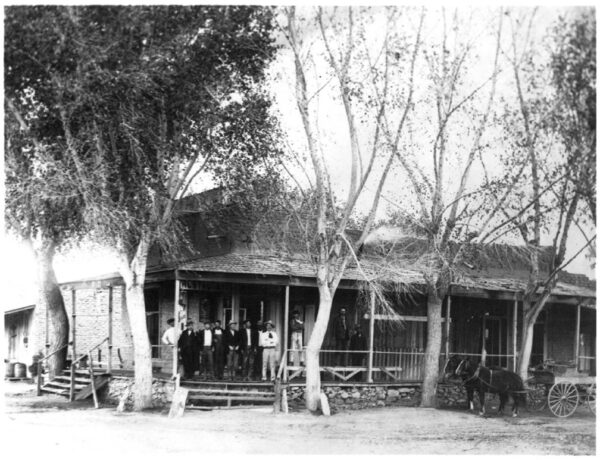

The town of Fairbank originated in 1881 as the community of Junction City, located along the New Mexico and Arizona Railroad’s Benson-to-Sonora rail line. Towns tended to spring up around transportation hubs, and this was the case here, with a general store, post office, and a saloon present in 1882. The following year the town was renamed Fairbank after Nathaniel K. Fairbank, a Chicago merchant. The community continued to grow with more people, stores, and saloons. The Montezuma Hotel opened to provide a place for visitors and people waiting for the train. Among the new residents were Chinese men, who grew produce that was sold in the nearby towns of Tombstone and Bisbee. Stamp mills, where ore was smashed into small pieces, were located to the north and south of Fairbank along the river.

Tragedy struck in August 1894 when monsoon rains caused the San Pedro River to flood the community. The Montezuma Hotel was among the buildings damaged by four feet of water.

The Fairbank townsite was located within a Mexican land grant, the San Juan y las Boquillas y Nogales. In 1901 the Hearst family purchased the grant and in 1905 most town residents were evicted. By 1905 only 25 people lived there. The number increased afterward to between 100 and 200. But after World War II the families drifted away. The town was completely abandoned in 1973. The Bureau of Land Management took over the townsite in 1986.

During the 2002 excavations the remnants of the Montezuma Hotel were found north of the road. The lower portions of its adobe walls are well preserved. The 1894 flood was visible as a layer of collapsed adobe bricks lying beneath a later floor from when the hotel was rebuilt.

Nearby, to the south, was an outhouse filled with trash from the hotel’s saloon. Bottles with well-preserved paper labels once held absinthe, cognac, beer, lager, and vermouth. Also found were a pair of dutch ovens, a portion of a Chamberlain Stove Company stove, and a tuning fork. Medicine bottles present were a Dr. Thenard’s Gold Lion Iron Tonic, Dr. Harter’s Wild Cherry Bitters, and Dr. J. Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters. In the early 1900s chemists examined many patent medicines and the Hostetter’s Bitters were found to contain about half alcohol, likely making someone taking it forget their troubles for a while.

Another find, likely a prized possession that once held perfume, was a bottle modeled after a Victorian-era girl holding a muff.

There was plenty of evidence for the Chinese men living at Fairbank. This included dishes, parts of opium pipes, and Chinese sauce jars. Animal bones from a trash deposit associated with the Chinese included sea bass, snapper, grunt, drum/croaker, frog or toad, duck, chicken, cattle, and pig. As seen elsewhere, Chinese immigrants ate a greater varieties of meats than their European and Mexican compatriots.

In recent years the BLM has stabilized buildings and opened a museum and gift shop in the old schoolhouse. There is a trail leading to the Fairbank Cemetery and the Grand stamp mill. You are likely to see birds, insects, and reptiles on the trail. In particular, the vermillion flycatcher likes the site and will be swooping around catching insects in the picnic area.

Learn more about Fairbank at the BLM website.