Ancient Technologies: Hohokam Etched Shell

Desert Archaeology shell specialist Chris Lange explores a fascinating bit of Sedentary period Hohokam craftwork.

The Hohokam people were not only successful farmers and irrigation canal builders, but were also craftspeople, creating tools and ornaments out of bone, stone, and shell. The shell crafting tradition of the Hohokam sets them apart from the other precontact cultural groups in the Southwest US. In perhaps the best-known example, an extensive shell procurement and exchange network resulted in Glycymeris bracelets being common items on sites in the Hohokam core area of central and southern Arizona, made from shells procured from the Gulf of California, over 100 kilometers to the southwest.

I’d like to take a closer look at one of their most unique technological achievements, which is creating etched shell. Just what is it? Emil Haury called it a form of intaglio patterns. An intaglio is created by incising a figure on a hard material that is depressed below the surface so that an impression from the design yields an image in relief. How did the Hohokam achieve this technology? First, they would need a resistant material (the “resist”), such as wax or pitch (possibly from a mesquite tree) that would be applied to the shell surface in areas of the design to be protected against the corrosive effect of an acid. Next, they would need to use an acidic substance to chemically reduce the calcium carbonate of the shell where it was not protected by the resist, which would then leave a raised pattern or design. What acid might the artists have used? Indigenous people have long collected saguaro cactus fruit as a source of food and also a source of juice for wine making—still an integral part of the ceremonies of the O’odham, descendants of the Hohokam. The fermented saguaro juice would have been an effective weak acid.

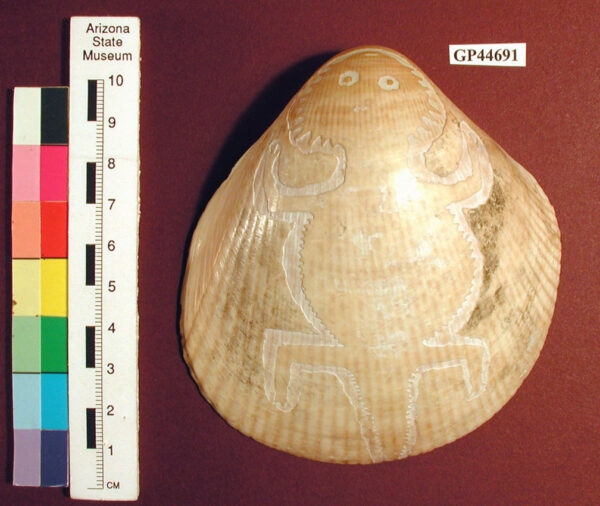

A sturdy shell, such as a large Laevicardium elatum, was typically chosen as the medium for etching because it provided a canvas large enough to draw a design that would be visible. Most of the etched Laevicardium shells that have been found show that the interior was the preferred side to be decorated, although occasionally the exterior was also used. Once the design was applied with the resist, the shell was immersed in the acidic liquid for an indeterminate amount of time. The longer the shell stayed in the acidic bath, the deeper the etching. Once the shell was removed from the acidic bath, it was washed off to remove the acid (stopping the etching process) and the resist was removed from the raised design.

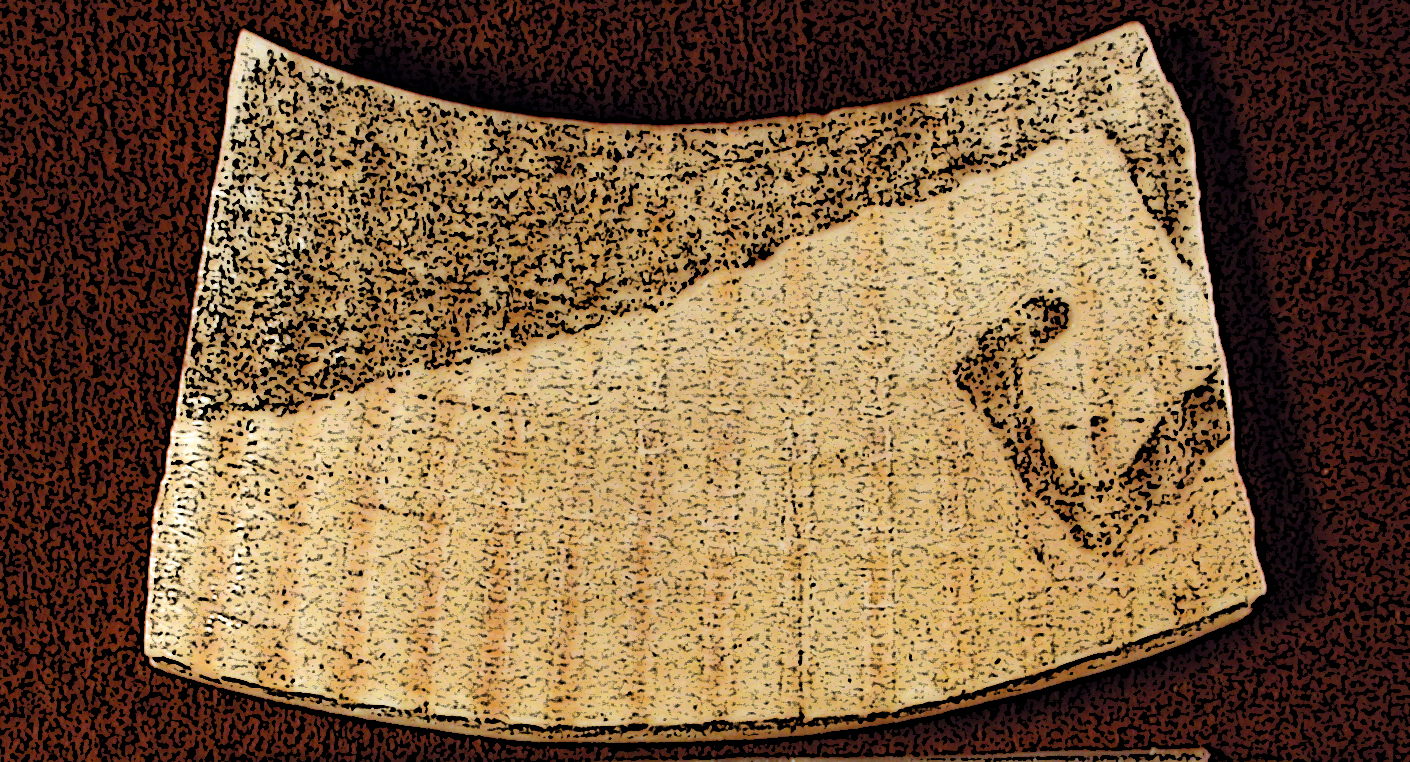

The Hohokam used designs on the shells that are also found on other media such as decorated ceramics and rock imagery. Most of the recovered specimens are fragmented, with only the occasional complete shell found. However, we can speculate as to what some of the designs would have been, such as geometrics and zoomorphics. An in-process ornament using a large Laevicardium shell with the image of a horned lizard was recovered during the 1934-1935 excavations at the Snaketown site (on the Gila River Indian Community, south of Phoenix). The resist still in situ as the shell had not been through the acidic bath yet.

Laevicardium shell with resist applied in a horned lizard design. It was never exposed to the acid that would have eaten away the shell surface around the protected design. (photo by Arthur Vokes)

Other specimens with pitch on them have been recovered elsewhere. A unique example is a complete Laevicardium shell that is both etched and painted, from a site near Rillito, Arizona north of Tucson. A similar geometric design is common on Hohokam ceramics made during the Sacaton phase (CE 950-1150).

Laevicardium shell with an etched and painted Sacaton phase geometric design (left); closeup view (right). (photo by Arthur Vokes)

The distribution of shells with acid etching seems to be limited to the Hohokam area and is primarily from contexts dating to the Sacaton phase, making this technology a reliable horizon indicator. However, one specimen from the Phoenix area was associated with the Santa Cruz phase (CE 850-950), and another recovered south of Apache Junction at the Siphon Draw Site was dated to the Santa Cruz-Sacaton Phase transition. Only about 40 specimens of etched shell plus 12 specimens with the resist material on the shell have been recovered to date, with only small quantities (one or two pieces) of etched shell reported from any of these sites. Few have been recovered from the Tucson area. Other than the amazing etched and painted shell found near Rillito, one piece of etched shell was found at Honey Bee Village in Oro Valley, and one at Hodges Ruin in Tucson. Eleven pieces of etched shell were recovered from Snaketown.

Only one example has been recovered from a mortuary feature, a cremation at the Gatlin Site in the Gila Bend area near the Arizona-California border, while the majority of the etched shells seem to be associated with domestic features such as house floors, house fill, and trash deposits. The limited spatial and temporal distribution of this unique ornament form leads one to speculate that the technique of etching shells was perhaps limited to a few specialists and kept secret through ceremonial restrictions. It is puzzling that more examples are not known from mortuary contexts. However, it has been suggested that the etched shells were not possessions of individuals but instead were possessions of sodalities or some other organizations, which would have prevented them from being interred with an individual.

The etched shells that have been recovered suggest that the medium was restricted to the Hohokam heartland as well as the Santa Cruz Valley. It doesn’t appear as if they were traded outside of the Hohokam area, as there haven’t been any examples found to date. This would imply that the exchange of this unique ornament had limited social boundaries. Although this technology was observed at several sites, research to date indicates it disappeared from the Hohokam repertoire of shell ornaments after the end of the Sacaton phase. It is suggested, then, that etched shell objects may have been part of a prestige sphere of conveyance, one that was limited by ritual ties. Thus, it appears that when the rituals were no longer performed or the specialists died, the knowledge died with them.