Mark Elson: Career Retrospective

Desert Archaeology founder and vice president Bill Doelle pens a testimonial to principal investigator, archaeologist, and volcano aficionado Mark Elson on his retirement.

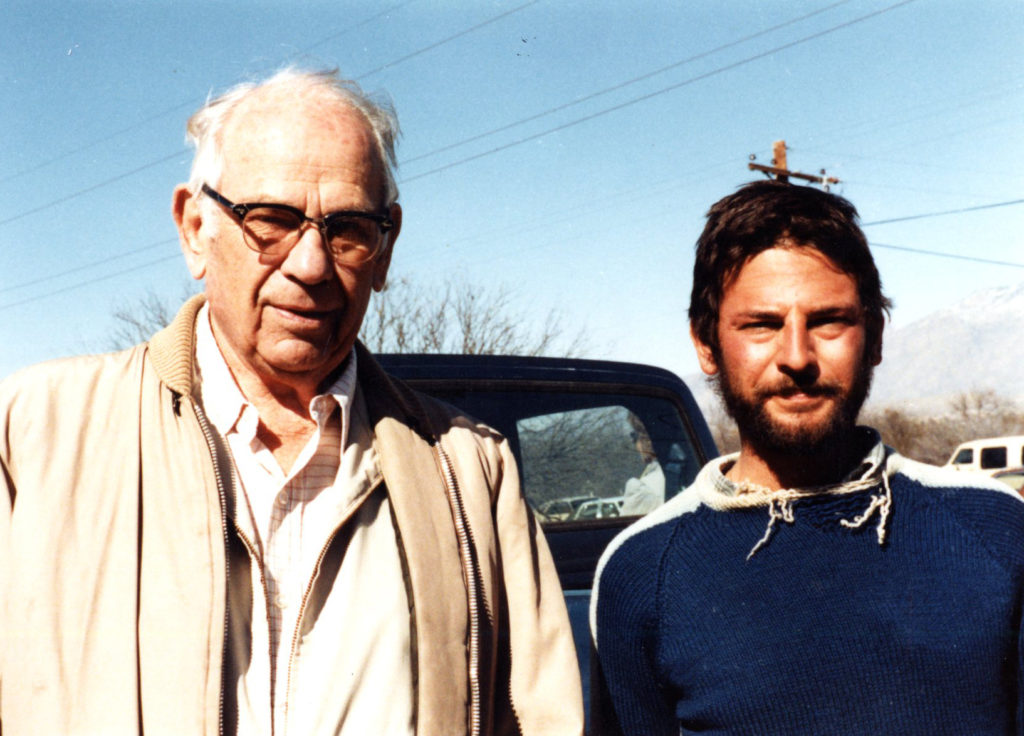

Mark Elson slipped into Tucson while I was away. I arrived in 1972, and I departed for a little over three years in late 1978. Upon returning to Tucson in 1982, Linda Mayro and I opened the Arizona Division of the Institute for American Research. That is the ancestor of Desert Archaeology as well as Archaeology Southwest. Jim Bayman, now a professor at University of Hawaii, was the first professional archaeologist hired by the Institute. He and I worked together at the Tohono O’odham community of Nolic in early 1982. The second project for the Institute addressed the impacts of a City of Tucson road construction project that ran through the west edge of the Valencia site, a Hohokam ballcourt village on Tucson’s south side. I was still writing the Nolic report, so I looked for someone to take on the Valencia site.

Because the Institute was based out of our home at the time, I chose a meeting place at one of the restaurants just west of the University of Arizona’s Main Gate. My first interviewee was just departing when Mark Elson arrived. The choice between the two was an easy one, and I soon offered Mark the job. Then that bane of contract-funded archaeology hit—there were “complexities” to resolve, and the project was delayed. In those nascent days, there was no other work to offer a new employee to fill the waiting time. Mark did wait for a while, and then Dave Doyel offered real work up on the Navajo Nation, and that was the end of that employee.

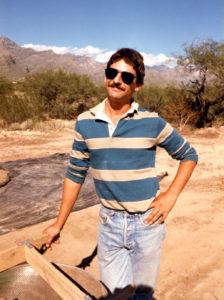

But not the ultimate end. In 1984, Mark was back in Tucson. He first worked on the Institute’s excavations at the West Branch site on the south side of Tucson. And then we took on the Tanque Verde Wash site, an interesting contemporaneous site on the far east side of town.

There, in late 1984 and early 1985, Mark directed the testing and subsequent excavation of some twenty pithouses at a Middle and Late Rincon locus (A.D. 1000-1150) of the larger site. It was a very high profile project. Dennis Wilkins, the local manager for Fairfield Homes, was a creative thinker, and he sought to take advantage of the publicity potential of this excavation. Extensive public tours—and special tours for schools—were later complemented by turning one of their model homes into a mini-museum. There was even a pithouse, reconstructed indoors. Those were heady times. As archaeologists, we were learning new things every day, and we were sharing that information widely with our local community.

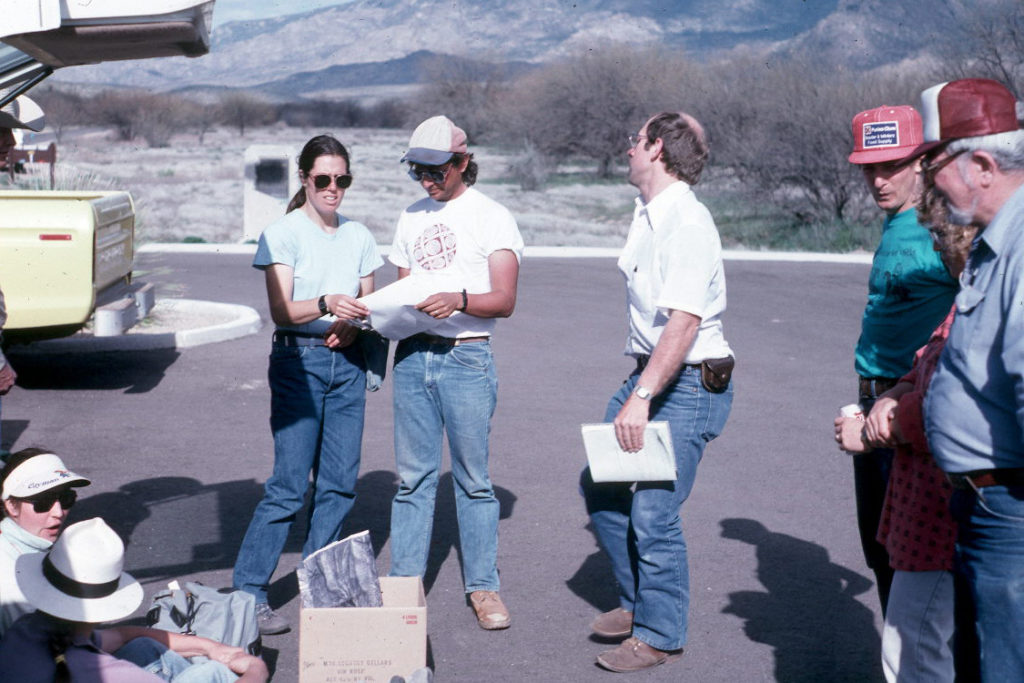

I had the opportunity to work closely with Mark on both field and report phases for a pair of projects. They were largely surface investigations of unplowed Hohokam ballcourt villages. The first was a return to the Valencia site and the second was the Romero Ruin in Catalina State Park. At both Romero and Valencia, we had the opportunity to make controlled surface collections in 25-meter grids. The analyses of artifacts—especially ceramics using the refined ceramic typology that our colleagues Henry Wallace and Jim Heidke developed—provided strong insights into site structure and change over time. And there was no need to excavate. Fortunately, too, Romero is protected within Catalina State Park and Valencia is protected by Pima County.

Debbie Swartz (left) and Mark Elson (center) prepare for a day of survey at Catalina State Park and the Romero Ruin.

New information accumulated rapidly from field results at the Valencia, West Branch, Tanque Verde Wash, Ventana Canyon, Romero, and Los Morteros sites from staff members Henry Wallace, Mark Elson, Fred Huntington, Al Dart, Mary Bernard, Deb Swartz, and Jim Heidke. Lisa Eppley had a dual role as analyst and lab director, ultimately shifting to full-time lab director. These efforts set Desert Archaeology on a major research track for the Tucson Basin. Much of that was brought together in the 1986 Second Tucson Basin Conference that I co-organized with Paul Fish that was published in 1988. One minor downside of these multiple local projects—we had become fairly “typecast” as Tucson Basin archaeologists.

Then, in 1987, ADOT announced a pre-bid tour for a data recovery project that would focus on a major expansion of State Route 87 in the northern Tonto Basin. As our Tucson-based vehicle, full of Tucson-based archaeologists, arrived at the meeting location, there were stares of surprise from many of the other attendees. [Minor aside: Mark tells a completely untrue story that I had a seizure as we drove out of the Sonoran Desert, and they had to turn the car around to return to the last saguaro on the highway to revive me. I do recall that it was a beautiful saguaro, but it was only a minor quiver, not a seizure.] Mark had previous experience in the area from his work with the ASM Highway Salvage program, and he was to serve as our Project Director. We all buckled down and wrote a strong proposal that earned us the contract for the Rye Creek Project.

Mark Elson giving a tour of the Pyramid Point compound on the Roosevelt project in 1992, with Roosevelt Lake in the background.

Rye Creek gave us grounding in the Tonto Basin so that we were ready to bid on the next big thing—the Bureau of Reclamation’s project to address the impacts of raising the height of Roosevelt Dam. By that time we had separated from our nonprofit parent and had become an Arizona for-profit corporation, which today is still Desert Archaeology, Inc. We built upon our State Route 87 experience, we worked super hard, and we put together a proposal that won us the “mid-sized Roosevelt contract.” The Bureau of Reclamation had set up contracts for a small, a medium, and a large project, ultimately filled by Statistical Research, Desert Archaeology, and Arizona State University, in ascending order. Mark Elson, Doug Craig, and Deb Swartz directed the fieldwork. As the results of the Roosevelt project were being written up, new ideas began percolating out of the mix of personnel. Mark, along with Jeff Clark, began to see in the archaeological data increasingly strong evidence for past migration into the Tonto Basin, and they worked to improve the archaeological methods for inferring migrations.

When the Roosevelt project ended, over a decade had passed since I first met Mark. And the world of cultural resources management was evolving. In early days, working with a master’s degree and a good deal of field experience was generally feasible. With time, however, there was an increasing expectation that project directors and especially principal investigators would have Ph.D. degrees. Plus, Mark and several of our staff saw that the research opportunities they were able to pursue in CRM were of a scale and an intellectual potential that was rarely seen in academia. So there were real incentives to pursue a Ph.D. Mark became Desert Archaeology’s first employee to use CRM data as the basis for earning a doctorate, completed in 1996. And he had the ambition and discipline thereafter to turn that dissertation into a University of Arizona Anthropological Paper, titled Expanding the View of Hohokam Platform Mounds: An Ethnographic Perspective, published in 1998.

So what was an aging, newly minted Ph.D. to do? Fortunately, ADOT had plans to widen U.S. 89 north of Flagstaff. Again, there was an intensive investment in the proposal process by a team of Desert Archaeology staff that was led by Mark. And it achieved success. Over the course of two field seasons over two summers, 40 Cohonina and Sinagua sites were tested and most were further excavated.

Mark Elson (left), Debbie Swartz, and Terry Samples (both holding maps) conducting an information sharing meeting for the US 89 project, 1988.

Mark Elson (center) and Sarah Herr (large hat, lower right) excavating a masonry pitroom at the Full House site on the U.S. 89 project.

In the process, Mark was afflicted by a research focus that he has not been able to shake ever since—the human impacts of volcanism. In this specific case it was the eruption of Sunset Crater, but it has led to a whole series of derivative interests and pursuits in subsequent years. The U.S. 89 project was multidisciplinary, it involved extensive Native American consultation, and it challenged some long-standing views of Flagstaff area archaeology—particularly the nature and dating of the Sunset Crater eruption.

It took the pursuit of outside funding from the National Science Foundation to address that topic in greater depth, but Mark and his colleagues have made the case that the eruption was probably relatively short in duration and more likely happened closer to 1085 than 1066. While that seems a relatively short time difference, the fact that archaeologists in the Phoenix area are arguing that the ballcourt system there underwent dramatic changes in 1075, and new ballcourts are known to have been established in the Flagstaff after the Sunset Crater eruption, is more than a little interesting. I have tried to get Mark to take on that topic in earnest, and this blog post is my final attempt to do so…..

By the time Mark finished up the U.S. 89 project, he had really put on serious years—said the blog author who is much older than Mark. So we started giving him more administrative responsibilities. He also began a teaching partnership with Dr. T. J. Ferguson on the Cultural Resources Management Class at the University of Arizona. He was also able to work with various colleagues such as Jeff Dean and Paul Sheppard (University of Arizona), and Kirk Anderson and Michael Ort (Northern Arizona University) on a variety of small research projects to refine the understanding of volcanism in the greater Flagstaff area generally, and on a broader scale through disaster research.

Front to back: Peter Pilles, Terry Samples, Debbie Swartz, Mark Elson, Linda Farnsworth, Bill Doelle, and Bob Gasser exploring the US 89 project area before the start of fieldwork, 1997.

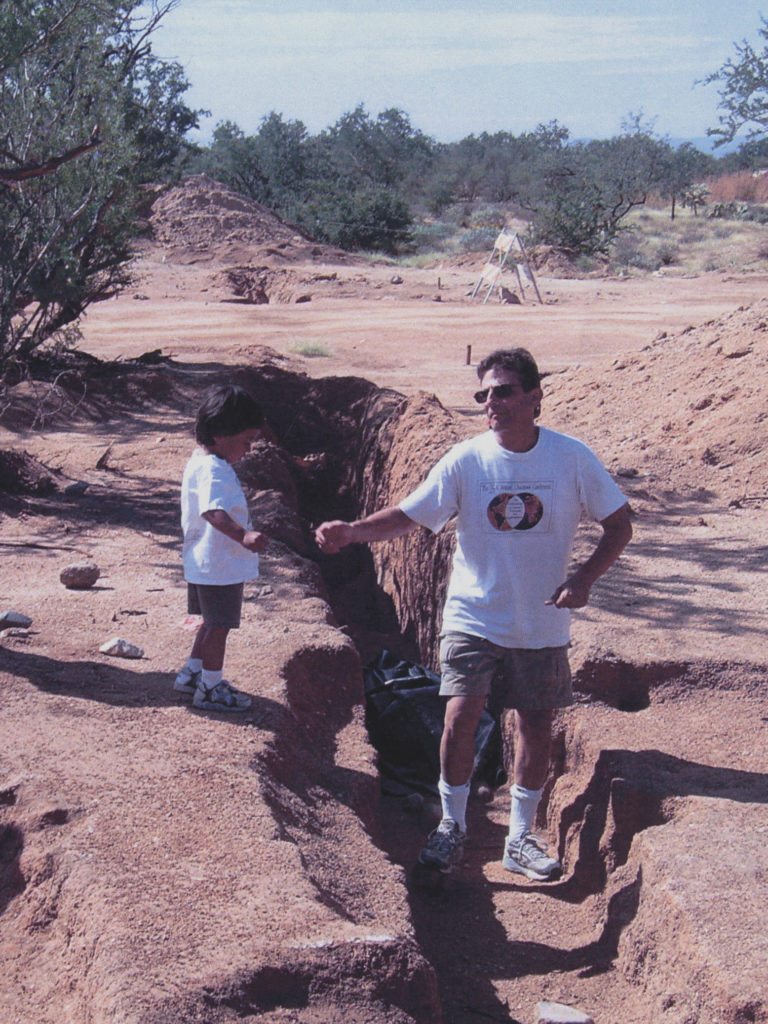

As key excavation projects for Desert Archaeology came along he got to return to the Tanque Verde Wash site, where Patti Cook directed field excavations, he wrote a synthetic chapter on the Classic period Yuma Wash site excavated by Deb Swartz, and he recently ran the field project at the Classic period Zanardelli site on Tucson’s south side. He also worked as a volunteer on the academic year field school at the Classic period University Indian Ruin, which was directed by Paul and Suzy Fish, now retired from the Arizona State Museum.

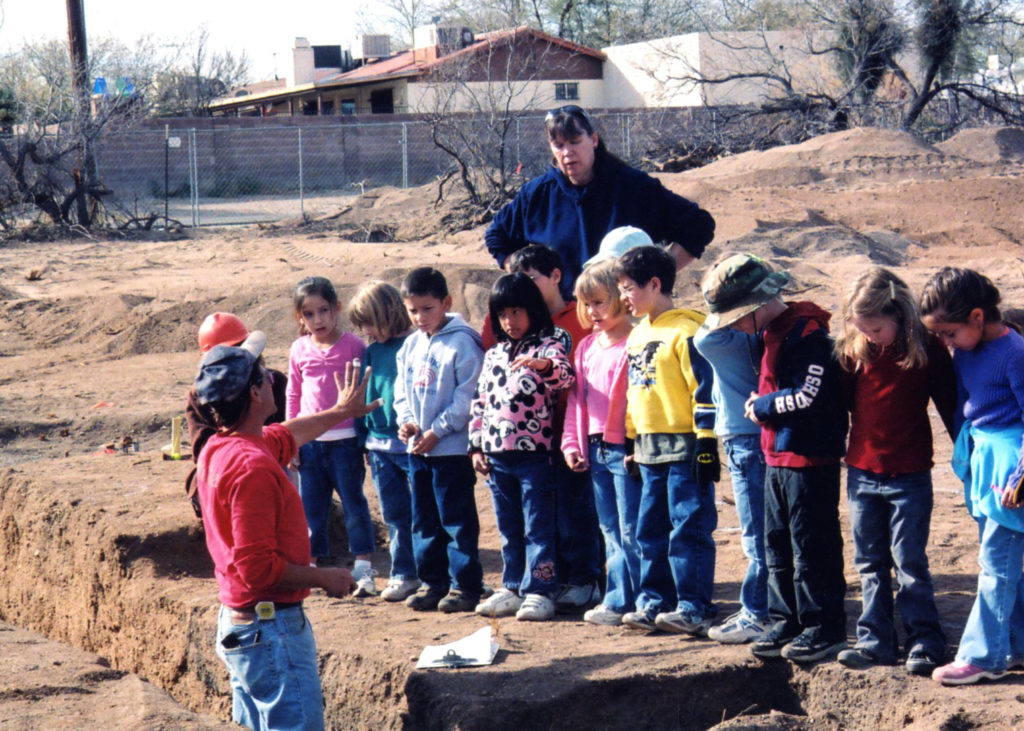

Mark (in red) conducts a tour for daughter Rachel’s (in Mickey Mouse jacket) kindergarten class on his return to the Tanque Verde Wash site.

It has been a very long time since Mark and I first met in 1982. Thirty-five years is enough time to accumulate a lot of positive research experiences as well as an occasional conflict. Mark is always focused on the big picture. Sometimes that picture is a large-scale research issue such as the role of platform mounds both ethnographically and specifically in the Tonto Basin. Or the focus could be the implications of volcanoes and the human experience of disasters. Sometimes it is impossible to get him to stop talking about volcanoes, in my humble opinion. But other times Mark’s focus was on communication within the company or on helping to set new sights on future projects and future personnel. He was a constant source of new ideas because he was always extremely social and curious.

Working with Mark has also involved working with his entire family. His wife, Deb Swartz, is a remarkable field archaeologist, and over time she has come to love writing concise, high quality reports. She has played a major role at Desert Archaeology, both on her own and as a field director on the very large projects that Mark has run. She has been a key ingredient to the success of the latter. Also, Deb and Mark decided to adopt two children from Guatemala—first Rachel and then Alex. Unbelievably, Rachel is already graduating from high school, and Mark is taking the lead on a home schooling program with Alex. So, one element of Mark’s retirement is about family and investing more time there.

Another expected element of Mark’s retirement is the pursuit of some of the research topics that couldn’t be readily resolved in the framework presented by CRM archaeology. He has always been very good at finding interesting and appropriate research questions wherever a CRM project plopped him down on the landscape. But now he doesn’t have those constraints. I hope he will find the time and the motivation to pursue those questions that still burn in his mind and that he will share that research with all of us. These 35 years have been a very special time to engage the challenges and unknowns of the world of CRM as it has unfolded and matured. Mark and I, and the many other Desert Archaeology employees that I have named, and others not explicitly mentioned, have had quite an adventure.

But the adventure isn’t over. For Desert Archaeology it will likely take new directions under its new leader, Sarah Herr. And, while Mark could certainly justify kicking back, my bet is that his energy and curiosity will carry him forward in exciting new directions. I wish Mark the very best. I thank him for all that he has given to Desert Archaeology, our staff, and to me over the years. It is rare when relationships last so long in a workplace. But Desert Archaeology has been an exceptional environment where work relationships have long persevered, with highly productive results.