Desert Archaeology in Downtown Tucson: Telling Their Stories

Homer Thiel is Desert Archaeology’s historical archaeology expert. He writes this week about our work uncovering the history of Block 91, now the eastern gateway to downtown Tucson, and how the everyday items we found illuminate the lives of the ordinary people who lived and worked there at the turn of the 20th century.

Over the last 27 years, Desert Archaeology has conducted archaeological fieldwork on about a dozen city blocks in downtown Tucson. Many of these projects were mandated by government regulations requiring mitigation of cultural resources prior to the redevelopment of downtown as new residences, businesses, government offices, and museums are built. Our excavations have uncovered features and artifacts dating to the prehistoric, Spanish (1694-1821), Mexican (1821-1856), American Territorial (1856-1912),and American Statehood (beginning 1912) periods.

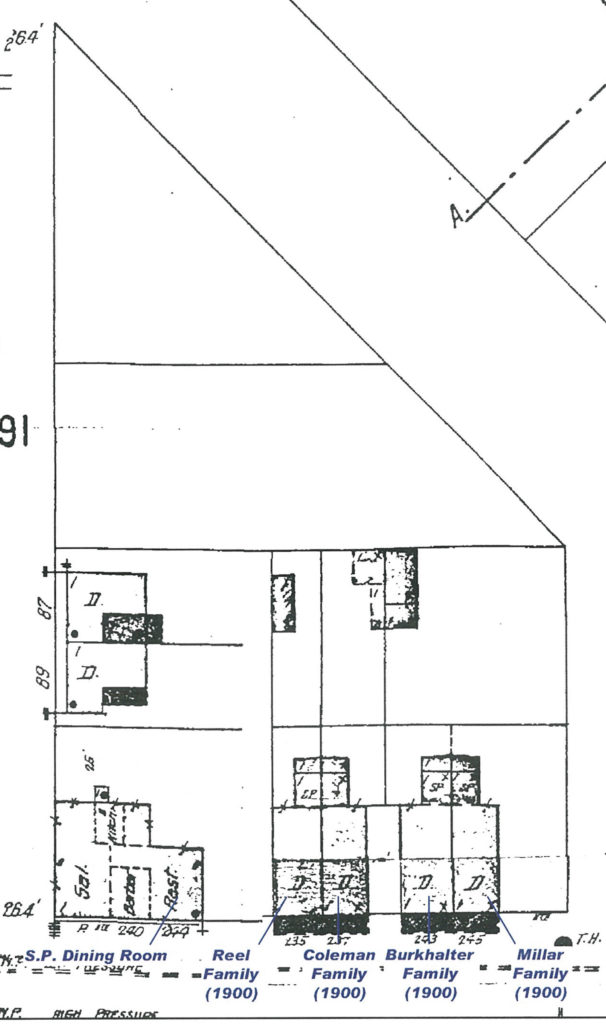

Block 91 is located at the northwest corner of North Toole Avenue and East Broadway Boulevard, formerly the site of the Greyhound Bus terminal, now the site of the Cadence apartment building and restaurants in the Plaza Centro development. Documentary research undertaken before our excavations began indicated the project area was first developed in the 1880s, with homes fronting 11th Street (now Broadway Boulevard). Residents included the families of Robert Millar, who was an undertaker, and Charles Burkhalter and James Reel, who worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad.

A photograph, taken in 1883, of the duplex occupied by the Burkhalter and Millar families in the early 1900s.

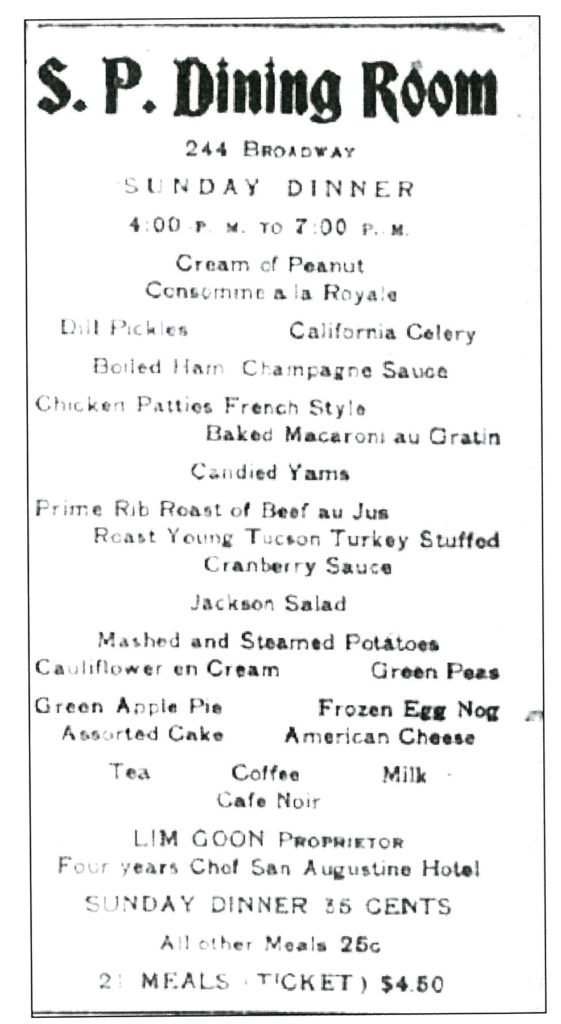

Beginning in the early 1900s, businesses opened on the block, including the Brady & Co. Grocery store, the Apache Hotel, the S. P. Dining Room, and a planing mill. Later, automobile-related businesses dominated the block before it became a parking lot and bus terminal.

The 1904 Sanborn Fire Insurance map, annotated in blue with information from the 1900 Federal census. 11th Street (now Broadway Boulevard) runs along the bottom of the map; the diagonal roadway in the upper right is Toole Avenue.

The City of Tucson acquired the land in a complex deal and Desert Archaeology conducted excavations there in 2011. A backhoe equipped with a wide scraping blade pulled up asphalt pavement and the concrete floors of the bus terminal, and then stripped away debris down to the underlying hard caliche layer, exposing 100 features. These included building foundations, a well, animal burials, and eight privy pits.

Aerial photograph of the Block 91 excavations with outhouse pits visible (photograph by Henry Wallace).

Prior to the installation of indoor running water in homes, people constructed privies—backyard bathrooms with a wood structure centered over a deep pit. The pits were periodically cleaned out, but often after five or ten years a new pit was dug and the old pit used for trash disposal. Archaeologists generally find three layers in an old privy pit. The bottom contains greenish-gray dirt (decomposed human waste) with items dropped in as people used the privy, including coins, pocket watches, dentures, and chamber pots. The middle layer contains trash generated by houses or businesses, deposited after the pit stopped being used as a privy. At the top is a layer of fill material dumped in to seal the hole. Privies are important features because their contents can often be linked to specific households, allowing archaeologists to explore topics not usually written down in surviving records. On Block 91, we excavated the privy pits to their bases. The materials we recovered allowed us to study different aspects of everyday life.

Photograph of the Feature 158 privy pit, showing some of the artifacts it contained (photograph by Homer Thiel).

Diet

Food and beverage containers, animal bones, and charred plant remains provide information on the diets of families and restaurant diners. The S. P. Dining Room was a Chinese-owned restaurant operated by Mr. Lim Goon on the block from 1905 to 1912. The privy and a pit associated with the restaurant yielded peppersauce bottles and raspberry seeds. The recovered animal bone revealed that customers could order beef, chicken, pork, and mutton. When combined with menus reported in newspaper advertisements, a better picture of the foods served in a Chinese-operated restaurant at that time can be developed.

Healthcare

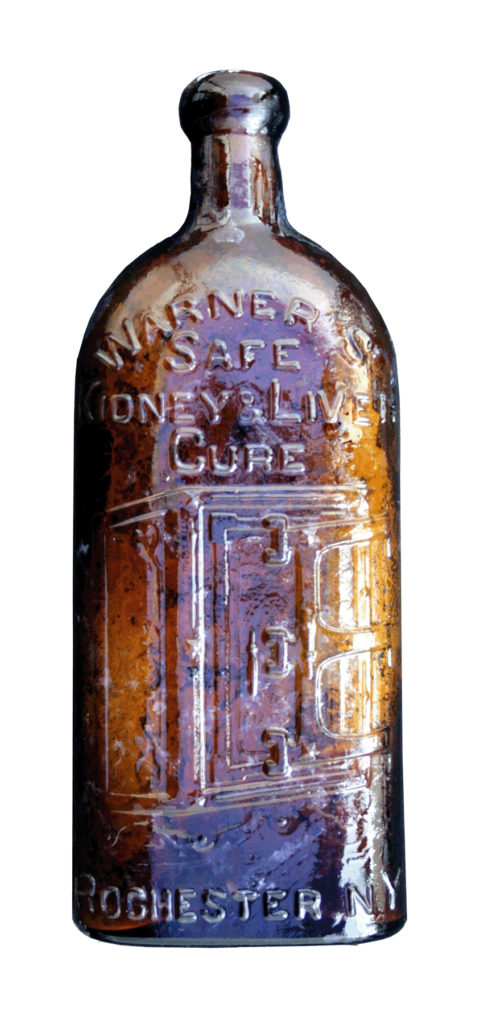

Numerous proprietary and pharmaceutical bottles found in the privies can reveal the healthcare problems of families. Embossed product names allow for the purported cures to be determined. A bottle of Dr. Jayne’s Tonic Vermifuge from the Reel family privy was supposed to “rid their bodies of the worms and clear out their nests.” The same privy also contained a bottle of Warner’s Safe Kidney and Liver Cure, which was supposed to cure kidney or liver disease, “female complaint,” constipation, and many other ailments.

A Warner’s Safe Kidney & Liver Cure bottle from the Reel family privy (photograph by Robert Ciaccio).

A unique find was a pessary from the Millar family privy. This S-shaped, hard rubber device was used by women, such as Margaret Millar, suffering from a prolapsed uterus, a problem caused when women had many children and/or they wore tight corsets that pushed their internal organs downward. Gynecological texts at the time recommended that women who used pessaries frequently douche, and numerous douche nozzles, tubing, and bulbs were found in privies as well.

Recreation

Labor-saving devices and the ability to hire servants allowed Territorial-era middle class Tucsonans to explore hobbies and to purchase a variety of new, more expensive toys for their children. China painting was a popular pursuit, with classes offered locally at the Tucson Conservatory. The painted dishes could be displayed as artwork, given as gifts, or used by the family. A set of butter pats and a saucer found in the Burkhalter privy were hand-painted by someone named G. Noble between 1880 and 1884.

Five small hand-painted butter pats from the Burkhalter family privy (photograph by Robert Ciaccio).

Crochet needles were also found in the Millar and Reel privies. Crocheting classes were offered in Tucson by 1873, and pattern books were available at local stores. A Tammany mechanical bank found in the Burkhalter privy was a toy that promoted saving money while entertaining children and adults alike.

An auction catalog photo of a Tammany mechanical bank and an identical bank from the Burkhalter family privy (archaeological example photographed by Robert Ciaccio).

The excavations on Block 91 and other city blocks in downtown Tucson have uncovered and preserved the stories of people and businesses who have largely been forgotten. Desert Archaeology has prepared reports on each project, some of which are available on the City of Tucson’s Historic Preservation website along with other resources on downtown history.