The Chinese Gardeners of Historic Tucson

Historical archaeologist Homer Thiel discusses the lives of Chinese immigrants in late 19th and early 20th century Tucson.

The first Chinese immigrants arrived in Tucson in the mid-1870s, several decades after Chinese people came to California during the 1849 Gold Rush. The initial arrivals operated restaurants, cooking American-style food at 25 cents a meal, something in demand with the many single men in the community.

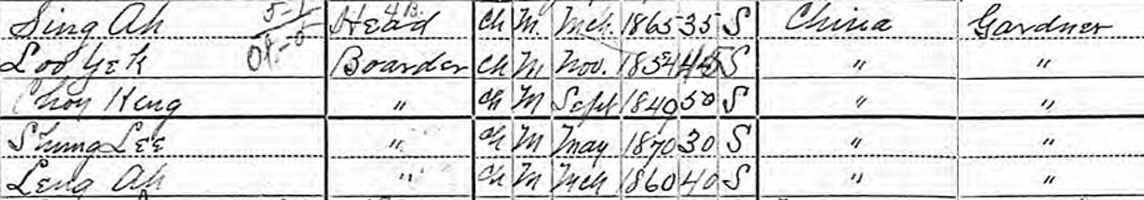

In 1879, construction of the Southern Pacific Railroad line between Yuma, Arizona and El Paso, Texas began. Thousands of Chinese men were hired to build berms and bridges and lay tracks. The railroad arrived in Tucson on March 20th, 1880 and a big celebration took place. One unexpected result was that about 120 of the over 1,000 Chinese laborers decided to stay in the community instead of moving eastward with the construction crew. The 1880 census lists 1,159 Chinese in Pima County. Of these 144 lived in Tucson and 13 at Fort Lowell. Most of the rest were working on railroad construction. The 1900 census finds 244 Chinese in Tucson, only 13 of whom were women.

Some of these men opened more restaurants, but others branched out into other occupations. These included laundry men, who washed clothes in the irrigation ditches in the Santa Cruz floodplain, personal servants, grocery store owners, and produce farmers.

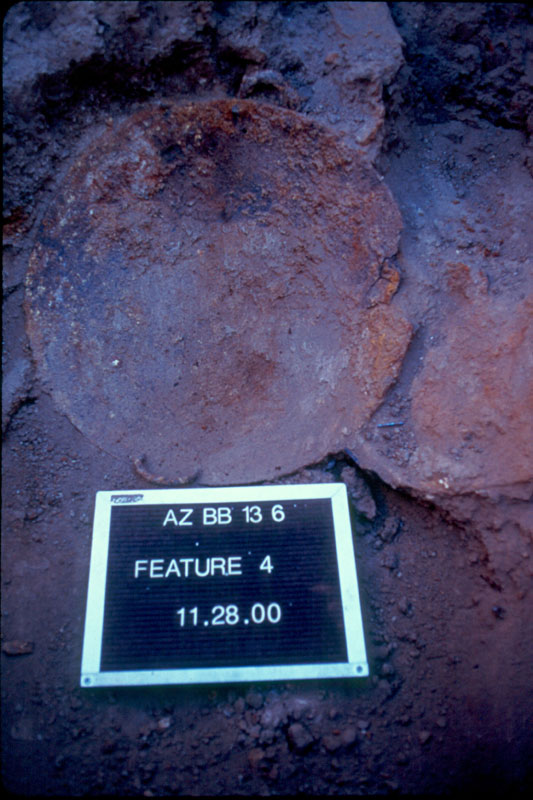

Desert Archaeology has excavated two sites occupied by the farmers. One was found beneath West Spruce Street during the “A” Mountain storm drain project, back in 1995. Testing revealed a large trash-filled pit containing many Chinese artifacts. The subsequent excavation uncovered part of a compound which once had adobe brick rooms. Nearby was a small privy pit, and the large pit turned out to be a soil mining feature later filled with garbage.

Archaeologists excavating beneath Spruce Street. Bob Rowe is in the foreground uncovering the compound.

In 2001, Desert Archaeology conducted excavations for the Rio Nuevo project at the location of the Leopoldo Carrillo House on Mission Lane. Carrillo had rented his house and fields to Chinese produce gardeners in the mid 1880s—later sparking a lawsuit in part because the Chinese men were using more water than their Mexican neighbors. We discovered a nine-foot-deep unlined well, filled with the items used by the Chinese men.

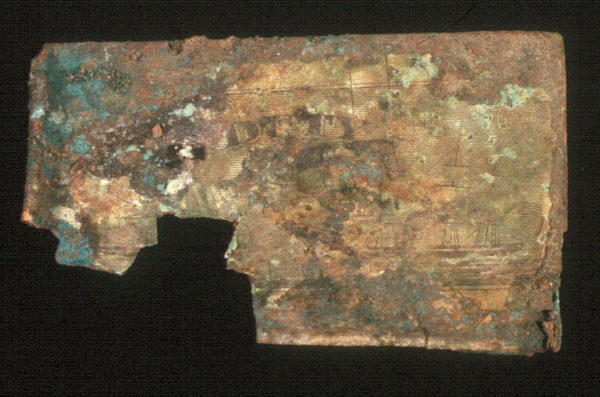

Life was difficult for these immigrants. In 1882 the United States Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which prohibited Chinese immigration, renewed in 1892 with the Geary Act. Chinese men in Arizona had to carry identification papers at all times, and were frequently harassed by a Chinese inspector. Court records at the National Archives reveal that many men were deported, while others had to have local businessmen testify that they were United States citizens. Other court records describe frequent crimes against Chinese men, especially storekeepers, several of whom were murdered.

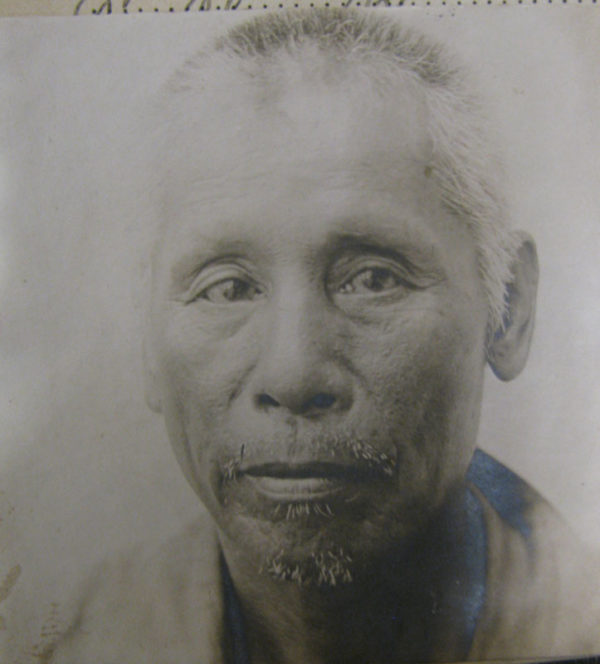

Gee Ling, a Chinese immigrant arrested in Tucson in July 1912 (National Archives, Laguna Niguel, CA).

We know that the Chinese gardeners grew much of the produce consumed in Tucson, crops including potatoes, sweet potatoes, onions, squash, cabbage, garlic, strawberries, watermelon, and carrots. They loaded their crops onto wagons and took them to restaurants and stores, and then peddled the remainder door-to-door. None of the surviving records describe what daily life was like for the gardeners outside of their fields. The artifacts and food remains found during these two projects can help create a better understanding.

Like many immigrants to the United States, the Chinese were very interested in maintaining much of their traditional culture. In part this was because many wanted to earn money and return to China, and as a result saw little need to assimilate. For others, the discrimination they routinely suffered, including the inability to bring wives and children from overseas, reinforced their Chinese identity.

Artifacts found at the sites reveal that the gardeners were purchasing Chinese-made cooking implements and food serving dishes from local Chinese-run stores. We found a wok in the Carrillo well, along with a teapot, small cups, rice bowls, and sauce dishes.

Chinese food service vessels. Back row has a Celadon rice bowl and tea cup. Front row has a Four Seasons spoon, sauce dish, and liquor or tea cup.

These vessels were used to cook and serve meals that included imported Chinese foods, including dried cuttlefish (a squid-like creature), bean paste, and soy sauce. They also incorporated foods from the Sonoran Desert, including cactus fruit and green weedy plants. Nineteenth-century accounts indicate the Chinese grew and consumed more vegetables than their neighbors. The Chinese also ate a wider variety of meats than their neighbors, mostly beef and pork, but also turtle, cat, and fish. The Chinese believed consuming a balanced diet of starches, meats, and vegetables was healthier, and it was, in comparison to the foods routinely eaten by European- and Mexican-American Tucsonans.

Buttons from Chinese garments were found at both excavation sites. Some of the Chinese men continued to wear traditional attire while working in their fields, but others wore Western clothing when out in public, in part because this reduced the chances of being bothered by the Chinese inspector.

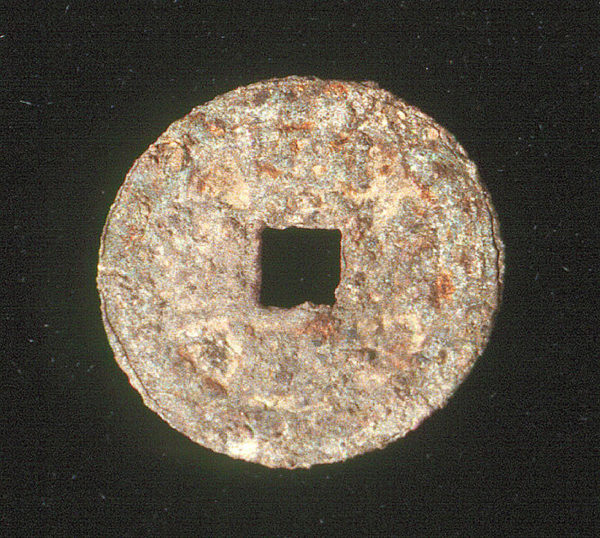

In their spare time, the Chinese gardeners enjoyed playing fantan, a game that utilized white and black glass gaming pieces. Many of the centuries-old Chinese coins recovered were probably used in gambling.

The men also drank imported wine, American beer, and many enjoyed occasionally smoking opium. Laws were passed making opium use illegal, but many immigrants continued to use the substance.

Small Chinese medicine bottles were also found, indicating a continued reliance on traditional medicines.

When we conducted the work beneath Spruce Street in the 1990s, elderly neighborhood residents stopped by and recalled watching the gardeners at work as late as the 1930s. Eventually, the men retired and lived in a set of buildings in the area that was torn down in the 1960s during Tucson’s ill-fated Urban Renewal Project. Archaeologist James Ayres documented the contents of these structures, and Florence and Robert Lister later wrote The Chinese of Early Tucson, a book available in local libraries. The Promise of Gold Mountain is a website documenting Tucson’s Chinese history and heritage.

The archaeological projects discussed in this blog were funded by the City of Tucson. The Rio Nuevo report discussing the Carrillo Well and its artifacts is available online. A PDF of the Spruce Street excavations is available for purchase. The featured image at the top of this post is from the 1900 US Census of Tucson.