World Without End: Archaeology of the Catholic Church in Tucson

Homer Thiel details some of the history and artifacts connected to the Catholic Church in Tucson.

In the mid-1690s, an Italian-born Jesuit priest, Father Francisco Eusebio Kino, set out from his mission in Dolores, Sonora, heading north into what is now southern Arizona. Kino was seeking to convert the local Native Americans to the Catholic religion, establishing missions and visitas (visiting missions). Kino was also an explorer, cartographer, and ethnographer. He was particularly interested in finding an overland route to the California coast.

In 1700, he established missions at San Xavier del Bac and at the village of S-cuk Son, an O’odham village at the base of Sentinel Peak (also known as A-Mountain in modern Tucson). A visita was a mission that lacked a resident priest. Priests from neighboring missions—in this case, San Xavier del Bac—occasionally traveled to the visitas to say mass, baptize people, marry them, and bury them. A church was constructed at S-cuk Son in 1771, and the San Agustín Mission was finished after the church at San Xavier—administered by the Franciscans, following the expulsion of the Jesuits from the New World in 1767—was completed in 1798.

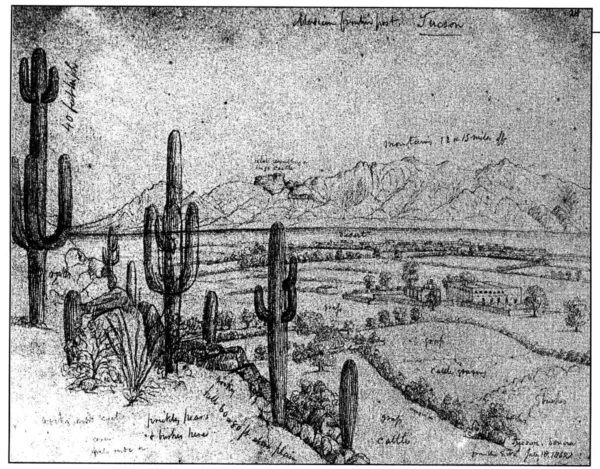

By the 1840s the San Agustín chapel was beginning to fall down. It was still standing in 1852, when John Russell Bartlett made a drawing while sitting on the side of Sentinel Peak, but was completely gone in April 1880, when Carlton Watkins took a photograph overlooking the Tucson Basin. Atanacia Santa Cruz, interviewed in the 1910s and 1920s, recalled that the exterior of the chapel was painted red and white.

A drawing made in 1852 by John Russell Bartlett, looking northeast from the side of Sentinel Peak. The San Agustín Mission is visible in the center right of the picture.

A portion of the 1880 Carlton Watkins photograph showing the two-story convento and the Leopoldo Carrillo house, built in 1871. Just to the left of the convento are two people standing next to the remnants of the San Agustín chapel.

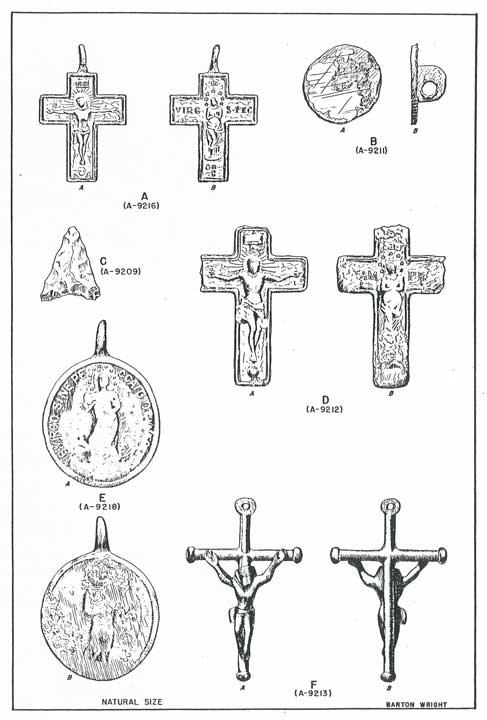

The Arizona State Museum excavated and mapped the chapel and portions of the two cemeteries in the mid-1950s, shortly before it was destroyed by the City of Tucson when the city converted most of the Mission site into a landfill. Several of the burials found contained brass crucifixes and religious medals, given out by Catholic priests to the local O’odham residents.

Artifacts recovered from the San Agustín Mission cemeteries during the 1950s excavations (drawn by Barton Wright, courtesy Arizona State Museum).

In 2000-2001, Desert Archaeology conducted work at the site and verified the chapel was no longer extant. However, pieces of red and white plaster found in nearby features appear to come from the chapel, verifying Atanacia’s story.

About one-quarter of the Mission had survived the landfill construction. We found the granary, the western compound wall, and the northern cemetery, which we left unexcavated at the request of the Tohono O’odham Nation. We excavated portions of the large middens (trash piles) that had survived. The Native American people living at the mission had discarded their trash, including chopped up animal bones, broken pottery vessels, and arrow points, in several areas. Among the many artifacts recovered were fragments from a seated woman figurine. The item may have been used in a native religious ceremony, perhaps for ancestor worship. This suggests that the residents of the mission retained their own religious beliefs, probably unobserved by the visiting Catholic priest.

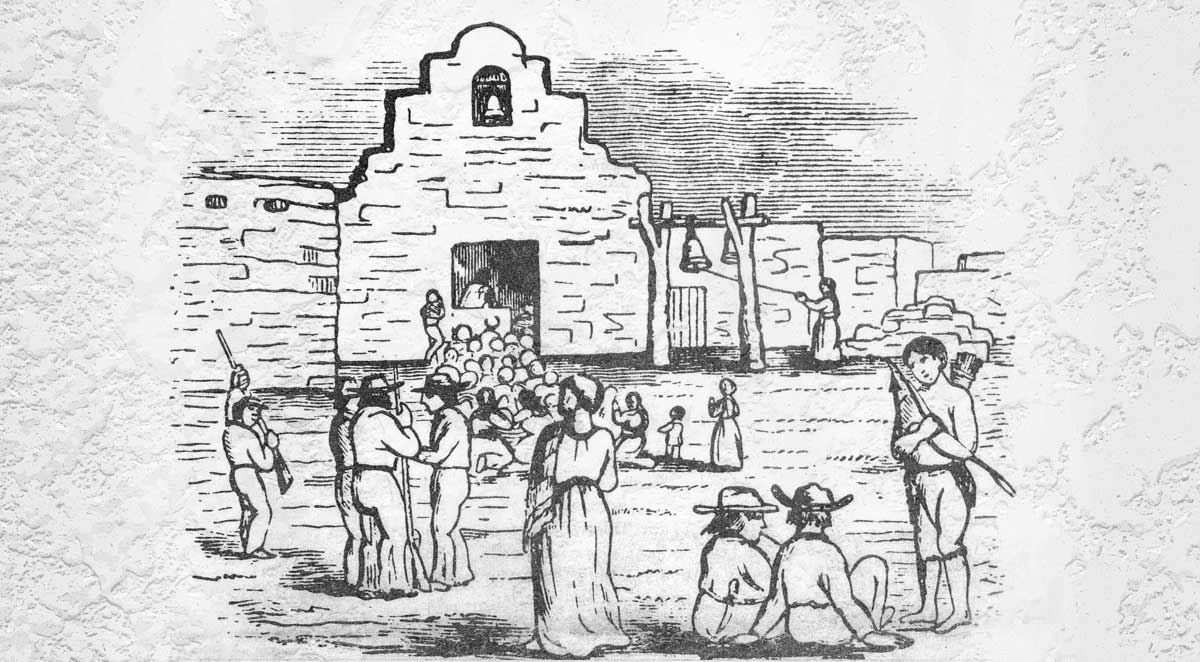

The Presidio San Agustín del Tucson was the Spanish and Mexican-era fortress established in 1775 on the east side of the Santa Cruz River. A chapel was built along its east wall. Father Pedro de Arriquibar served as the presidial chaplain from 1797 to 1820. During that time he was able to furnish the chapel with paintings, books, fabric items, and silver and copper vessels. When the U.S. Army assumed control of the Presidio in 1856, the Mexican soldiers departed, taking all of these items south to the town of Imuris, Sonora, along with the contents of the San Agustín chapel. Catholic priests resumed residency in southern Arizona in 1858, after a 30-year absence caused by the Mexican government expelling all foreign-born priests in 1828. During that time, in the 1840s, a priest from Magdalena occasionally visited Tucson, baptizing children and performing marriages. A June 1860 drawing shows a priest celebrating mass while standing in the doorway of the Presidio chapel. By this time the roof had started to collapse. The building was torn down soon afterward.

The chapel had burials underneath its floor and also on at least its south side (and possibly both sides). The cemetery had “a cross of medium quality iron with its gate and key.” Burials from the cemetery were excavated in 1969-1970 by the Arizona State Museum. In 1992, Desert Archaeology monitored the digging of a gas line trench dug along the south side of West Alameda Street. Human remains were quickly encountered, and subsequent excavations led to the removal of 20 burials. We found that many of the Presidio-era burials had cut through existing burials. When that happened, the exhumed bones were stacked up in the new grave. As a result, the remains of over 100 people were found in the 20 graves and the surrounding soil. Two copper wires found during the dig were once part of paper floral crowns placed on the heads of children and young adults, a symbol of innocence and purity.

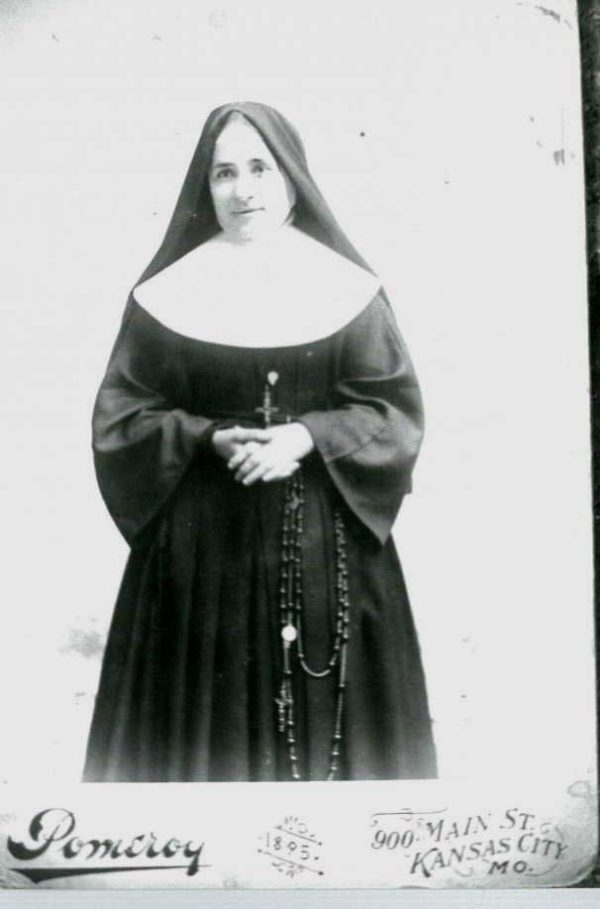

The Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet arrived in Tucson in 1870. These seven nuns opened St. Joseph’s Female Academy, where many Mexican girls were educated, St. Mary’s Hospital, and St. Joseph’s Orphans Home. In 1877, Cleofa León decided to become a nun and entered the novitiate. In July 1879, she became Sister Amelia, C.S.J.

Sister Amelia would go on to teach at a number of Indian schools, before dying in California in 1916. In 1999, Desert Archaeology’s work at the León farmstead led to the discovery of a brass-and-redwood crucifix, missing its Christ figure. Sister Alberta Cammack, C.S.J., later identified it as a nun’s cross.

Today the Catholic Church has numerous churches in the Tucson area. The downtown St. Augustine Cathedral houses one of the Presidio chapel’s bells, occasionally allowing it to be rung.

Resources

The featured image at the top of this post is “Church at Tucson on San Antonio’s Day, 1860,” from The Loyal West in the Times of the Rebellion by John W. Barber and Henry Howe, 1865.

A history of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet can be found here.