Archaeology Archive: Native Ceramics from Block 136

Jim Heidke and Homer Thiel examine the use of Native American pottery in Tucson’s historic Barrio Libre.

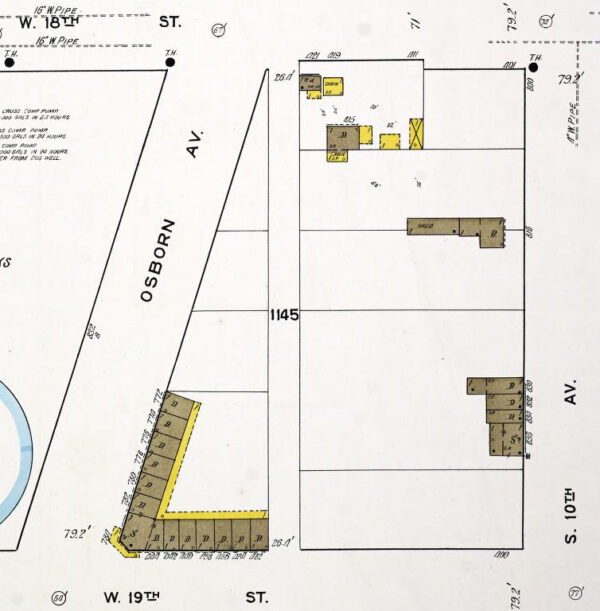

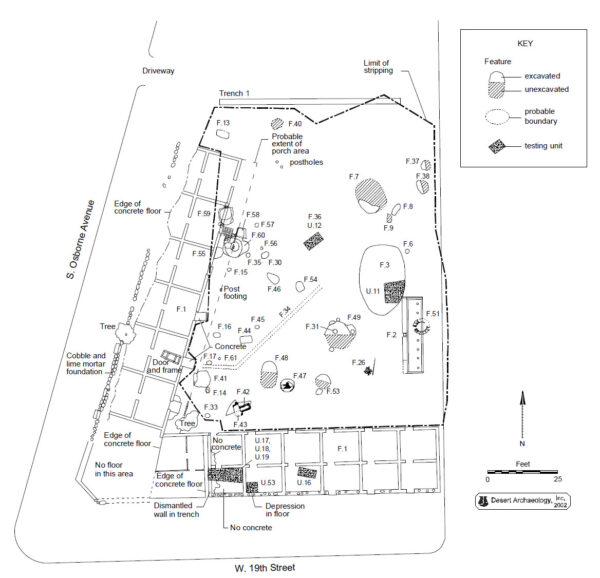

In 2001 Desert Archaeology conducted archaeological excavations on Block 136 in Tucson’s Barrio Libre. This barrio is located south of the downtown and was the home of many Mexican Americans, Native Americans, and African Americans during the Territorial (1856-1912) and early Statehood (beginning 1912) periods. Our work on Block 136 focused on an L-shaped apartment building occupied by Mexican immigrants and its backyard. A variety of features were present, including outhouse pits, a large soil mining pit filled with trash, planting pits, and an adobe bread oven.

Numerous artifacts were recovered from pit features in the backyard. Among these were 1,992 ceramic sherds manufactured by Native Americans. Ninety-one were Ancestral Native American (what we used to call prehistoric), most found in a roasting pit and the others likely arriving in adobe bricks made from soil dug out of a nearby archaeological site. The rest were manufactured by Tohono O’odham potters between 1860 and 1930.

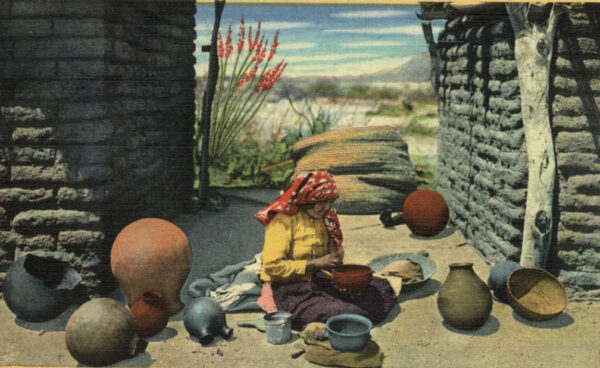

In 1962, Bernard Fontana, William Robinson, Charles Cormack, and Ernest Leavitt authored Papago Indian Pottery, a study of how ceramic vessels were made and used by the Tohono O’odham. Today the O’odham no longer use the word Papago, but the ceramic types established by these researchers continue to use the word.

During the Territorial and early Statehood periods, Native American ceramics were used for a variety of purposes in Tucson. Perhaps most common were Sú-u-te-ki-wá-i-kut (large and small water ollas). Like other historic O’odham pottery, the ollas had an organic temper: animal manure, which is visible in broken pieces as a black core. The use of this tempering material allowed water to slowly seep through the vessel, evaporating on the exterior and cooling its contents. Water was obtained from backyard wells or from a tanker wagon that traveled up and down streets, with city water installed throughout the Barrio Libre in the early 1900s. About 32 percent of the recovered reconstructible ceramic vessels from Block 136 were used for storage of either water or foodstuffs.

A Papago Plain Sú-u-te-ki-wá-i-kut (flare-rim storage jar) recovered from Feature 60 at Block 136 was probably used for water storage (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

O’odham cooking vessels were also used by the residents of Block 136, with 28 percent of the recovered pottery used for this purpose. Among these were comales (flat ceramic plates used as griddles to cook tortillas).

Two examples of Hi-to-ta-kut (bean boiling pots) were recovered. These are semi-flare-rim, incurved bowls with sooting on their exteriors from exposure to fire.

A Papago Red Hi-to-ta-kut or bean boiling pot from Feature 60 at Block 136 (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

A Papago Red Hi-to-ta-kut (bean boiling pot) from Feature 41 at Block 136 (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

Lastly, some O’odham pottery was used for serving food and beverages. A total of 40 percent of the recovered ceramics from Block 136 were used for this purpose, a much higher amount than was used by other households throughout Tucson. Several Bí-kut (serving bowls) were found.

A Papago Red Bí-kut (semi-flare-rim outcurved bowl) from Feature 41 at Block 136 (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

The function of some vessels is unknown. An unusual double bowl may have been used as a cup, but this remains uncertain.

One other Native American ceramic item was recovered that was not used for storage, cooking, or serving foods. This was a fired clay animal figurine. It had a head with eyes, nostrils, and ears, and had four legs. It resembles fired clay animals recovered from Hohokam sites and may be an ancient figurine found by the residents of Block 136.

Metal and commercially manufactured cooking, storage, and serving vessels were found in much larger numbers on Block 136. So why did some residents continue to use Native American pottery? The Mexican immigrant families may have used Native American ceramic vessels back in Mexico and continued using them once they arrived in Tucson. This usage may reflect a desire to retain traditions of their homeland, or perhaps they preferred certain qualities the vessels produced. Perhaps beans cooked in an O’odham vessel were simply better tasting than beans cooked in a metal pot.

The Block 136 project was funded by the City of Tucson.

Resources

A hard copy or PDF of Exploring the Barrio Libre: Investigations at Block 136, Tucson, Arizona can be obtained from Archaeology Southwest.