Axe Head Road Trip: What I Did on my Summer Vacation

Desert Archaeology ground stone expert Jenny Adams returns to the blog with a story of a summer road trip that showed her not only the half of the country east of the Mississippi, but several intriguing ancient axe heads as well.

This summer, during a tour of states east of the Mississippi, I visited the site of Moundville in Alabama, the Grand Village of the Natchez and the Emerald Mound in Mississippi, and Dickson Mounds in Illinois.

As a Southwestern archaeologist, the layouts and architecture of the Mound Builders sites were interesting (the French explorers who lived among the Natchez documented life at the Grand Village, with particular attention to the construction of Mound A and the building atop it that was used by the elite Sun families—take note, everyone studying Hohokam mound sites). As a ground stone specialist, it was interesting that at each of these sites, axe heads were the most prominent ground stone artifacts displayed and identified in their museums.

The result? On my summer vacation I learned that I do not know everything I need to know about ground stone axe heads.

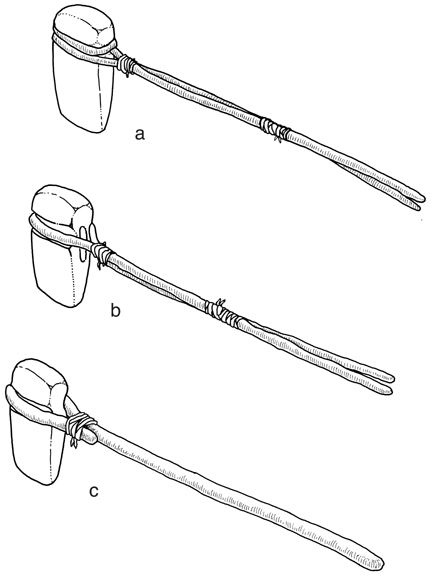

I’ve analyzed 186 axe heads from projects all over Arizona and the Four Corners area. They come in three varieties, defined by how they were modified for hafting to a wood handle: ¾-groove, notched, and full-groove. These hafting techniques were spatially distinct. Axe heads designed with a ¾ groove have one narrow, flat, ungrooved side. Sometimes a shallow second groove was ground into this side, oriented perpendicular to the main groove, so that a wedge could be inserted to tighten the head against the haft.

A Hohokam ¾-groove axe head without ridges from Honey Bee Village in Oro Valley, Arizona (photo by Rob Ciaccio).

Other variations include ridges on one or both sides of the groove. ¾-groove axe heads were manufactured in southern and central Arizona by Hohokam and Mogollon stoneworkers beginning about AD 450.

Notched axes were hafted with two opposing notches on the narrow edges. They have been found in contexts that date to about AD 750. As the name indicates, the hafting groove on full-groove axes completely encircles the head. These were manufactured by Anasazi stoneworkers. Although full-groove and notched axe heads co-occurred for some time in northern Arizona and the 4 Corners area, by A.D. 1000, full-grooved axe heads were the predominant design.

Line drawing of hafted axe heads. Top is a full-groove axe head with a double-wrapped handle. Middle is a ¾-groove axe head with wedge groove where a wedge would have been fitted to secure a tighter handle. Bottom is ¾-groove axe head with a J-handle (illustration by Rob Ciaccio).

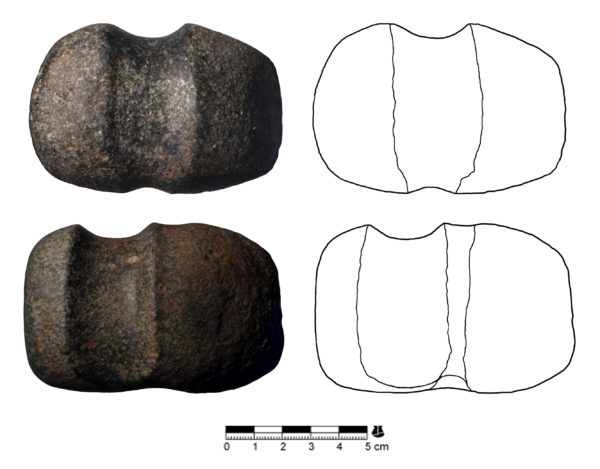

There is evidence that when individuals moved around from place to place with their axes, they maintained the hafting traditions they grew up with. This means that both ¾-groove and full-groove axe heads occasionally coexisted at a settlement, or—more rarely—the groove on a ¾-groove axe was extended into a full groove or a full-grooved head was reworked with a ¾-groove.

Regrooved axe heads from Turkey Creek Pueblo in the Point of Pines area, Gila County, Arizona (photo and line drawing by Rob Ciaccio).

To me this is evidence that the technological traditions learned by axe head manufacturers remained important to them, even when they were confronted with alternative ways of hafting an axe head. Additionally, I think that the long-term co-occurrence of different hafting technologies indicates that they were equally functional, with the choice of one or another depending on the traditions that were familiar to individual users.

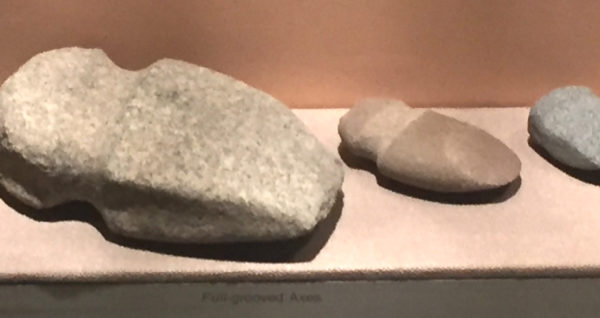

Imagine my surprise when the mound site exhibits had examples of both full- and ¾-grooved axe heads! Except for rock type, if these axe heads were dropped into the U.S. Southwest, they would not be recognized as foreign. At Dickson Mounds, which is under the auspices of the Illinois State Museum, the displays of multiple axe heads included celts—heads that were hafted without a groove by inserting them though a slot cut into a wooden handle. Celts have not been found in the U.S. Southwest. Adding to my surprise was the fact that axe heads were first manufactured east of the Mississippi during the Archaic period, perhaps as early as 6000 BC—predating the first appearance of nearly identical designs in the Southwest by more than 6,000 years.

A variety of axe heads recovered from the Modoc Rock Shelter, Randolph County, Illinois, in a display prepared by the Illinois State Museum at the Dickson Mounds site. Modoc Rock Shelter has a long history of occupation, so the axe heads are not time specific. Upper center, a full-groove axe head that might have started out as a notched axe head; right and lower center, 3/4-groove axe head with no ridges; left, ¾-groove axe head with ridges (photo by Jenny Adams).

Intrigued by the display at Dickson Mounds, I decided to go to the Illinois State Museum in Springfield to see if I could find out more. And there it was: a ¾-groove axe head with a wedge groove that had been redesigned with a full groove. Clearly, axe-hafting traditions I recognized in the U.S. Southwest have a much broader geographic distribution than I previously knew and far greater time depth east of the Mississippi.

Axe head display at the Illinois State Museum. On the left is a ¾-groove axe head with a wedge groove (visible on bottom edge) that was later redesigned with a full groove. Note the full-groove axe head on the right (photo by Jenny Adams).

What has not changed in my thinking is that the technological traditions employed by ancient axe head manufacturers were vitally important to axe head users, persisting no matter where an individual’s travels led. What I learned on my own travels on a theoretical level is that axes were much slower to come to the U.S. Southwest than they were to the east. And what I learned as an archaeologist is that we all need to get out more often to broaden our horizons beyond the U.S. Southwest.