How We Ask Questions: CRM Archaeology and the Land Between

This week’s blog is by Sarah Herr, owner and president of Desert Archaeology.

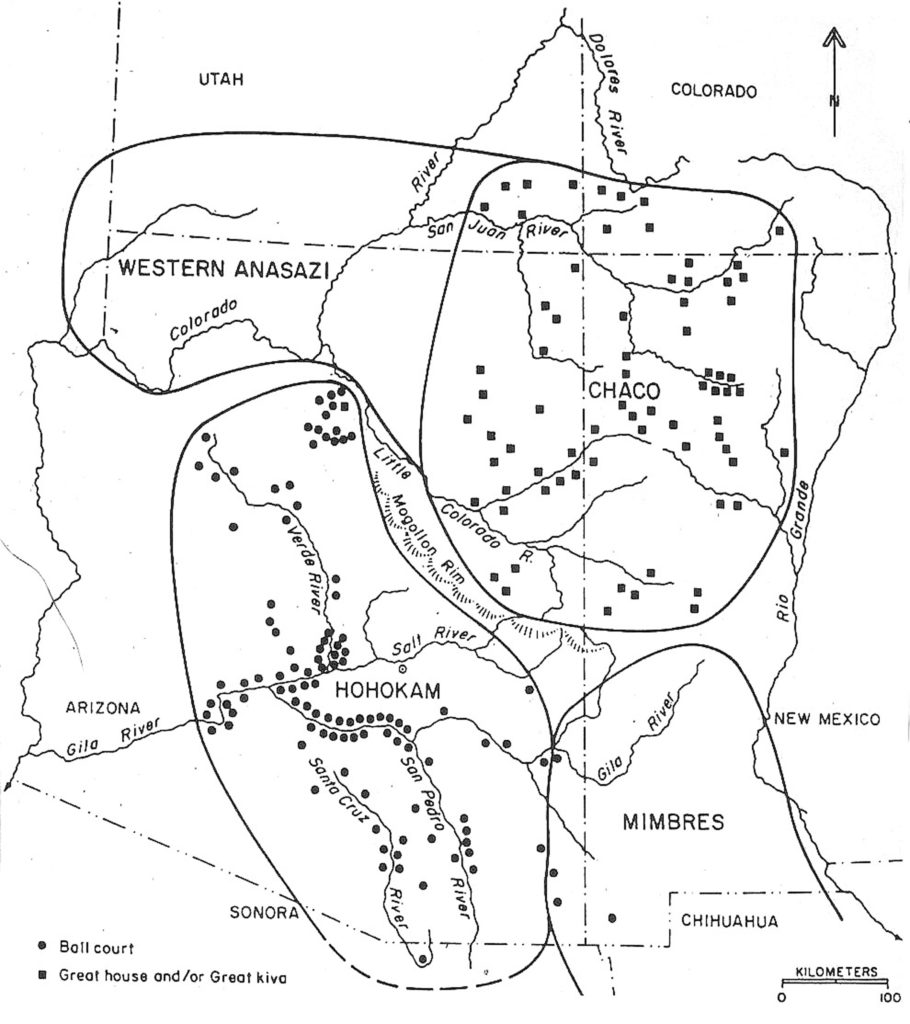

What do you imagine when you think of archaeology sites in the Southwest? Cliff Palace and other dwellings at Mesa Verde, silently keeping watch over the canyon? The towering architecture of Pueblo Bonito, oriented with cosmographic phenomena? The vast remains of the ancient settlement at Paquime in the hot Chihuahuan desert? Whatever comes to mind, where I work is very likely not that. But, if you know where the far margins of these archaeological cultures are, take a few steps beyond them. Those are the places where I work–often with rugged topographies or located miles from perennial water. Places that aren’t really lived in much now, and were sparsely populated throughout much of the past as well.

Despite being located in “the land between” major cultural areas, these places were the central places of everyday life for thousands of people in the past. And there are far more “betweens” than there are “centers” across the Southwest. Most of the projects I have worked on at Desert Archaeology have been connected to highway construction by the Arizona Department of Transportation. Across the country, departments of transportation have been some of the great funders of archaeological work, and in Arizona, as elsewhere in the west, highways go through a lot of between places. Because historic preservation laws require archaeology in advance of transportation projects, we therefore study a lot of these between places.

The Snowflake Passing Lanes project, showing modern Arizona State Route 77 running along the corridor once built to connect Holbrook, Arizona, and the railroad to Fort Apache (photo by Henry Wallace).

When I talk to college students about jobs in cultural resources management (CRM) archaeology, one of the dichotomies I present is the difference between how archaeologists in universities and my CRM colleagues approach research. For example, Patti Crown, a professor at the University of New Mexico, asked, “how did Chaco people use cylinder jars?” and then began her research with sherds and complete vessels in museum collections around the country. Tim Kohler (Washington State University) teamed with colleagues to ask, “how does the organization of communities change when climate changes?” They complied data about past settlements from the Four Corners region, an area of long-term archaeological fieldwork and data, including superb tree-ring reconstructions of past climate.

In CRM archaeology, instead of starting with a question, we start with a place that is defined by our client’s development or land management needs. Then we ask, “what are the archaeological characteristics of this place and what can it teach us?” We develop our research design and sampling strategies from there.

Map showing the Mogollon Rim area’s status as “the land between” the Hohokam, Mimbres, and Anasazi core areas (from Regional Organization in the American Southwest, Figure 2-3, by David E. Doyel and Stephen H. Lekson, in Anasazi Regional Organization and the Chaco System, 1992).

I’ve been thinking for years now about how the people lived in between. What brought them to these places? What were their lives like beyond the boundaries? How different were their values, their workday, their food, from people who were Hohokam, Mimbres, and Chacoan? Who were they? How can I use notions of historic frontiers and pioneering to understand these homesteaders of the ancient past?

Overview towards the State Route 260 project area from an overlook on Arizona SR260 above the Mogollon Rim. Modern SR260 east of Payson generally follows the course of the old wagon road that linked the homesteads and government buildings situated in each alluvial valley. It probably follows the best-watered and, often, gentlest topography that makes a somewhat logical line through the area (although a few bridges across ravines make travel easier today).

CRM archaeology spurred by highway projects challenges us to ask questions we wouldn’t otherwise think to ask, substantially expanding our knowledge. We examine the places the road takes us. We study places just being settled, flourishing, and in decline. We look at sites big and small, and some things that are barely sites at all. Along these corridors we work our way from places we are familiar with to places we know little of, learning more about the variation of people’s lives and, so, the diversity of human experience on the journey.

These places between may be the “flyover states” of the past, and our understanding of the people who lived there, as well as the people in the more central places, is essential to understand the big picture of society now and in the past. Our work in CRM archaeology can help.

(Thanks to Reuven Sinensky and the UCLA anthropology graduate students who got me thinking about how I came to ponder peripheries.)