The Ancestral Native American Past in Downtown Tucson

Homer Thiel takes a long view of Downtown, detailing the traces of people who lived in the area thousands of years before Europeans arrived in what is now southern Arizona.

Hidden beneath the streets, sidewalks, parking lots, and buildings of downtown Tucson are traces of our community’s Ancestral Native American past. Archaeological fieldwork since 1943 has gradually uncovered evidence that the terrace on the east side of the Santa Cruz River floodplain has been occupied for thousands of years. Beginning in 1954, people have claimed that Tucson is the “oldest continuously inhabited community in the U.S.” While this is debatable, archaeologists have determined that the downtown core of Tucson has been occupied for at least 4,500 years.

A headline from the Arizona Daily Star from December 10, 1954.

In all, 80 pre-contact (a blanket term for the thousands of years preceding the arrival of Europeans in the Southwest) features have been documented downtown. Most have been encountered due to cultural resource legislation that requires archaeological fieldwork prior to construction or the monitoring of ground disturbance within the boundaries of a known site.

A map showing some of the pre-contact features and the outline of the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson (drafted by Catherine Gilman).

Excavations prior to the construction of the Pima County Consolidated Justice Court complex on Stone Avenue located the oldest known feature, a pit dating to the Middle Archaic period (3500-2100 BC). A radiocarbon date from mesquite charcoal yielded a date of 2620-2460 BC, roughly 4,500 years ago. During the Middle Archaic period people moved their settlements across the landscape, gathering wild plants and hunting animals including jackrabbits, cottontails, and deer.

The Early Agricultural Period began around 2100 BC with the Silverbell Interval, which lasted until 1200 BC. This interval saw people begin to grow maize (corn) along the Santa Cruz River. On the west side of the river, south of Congress Street, 4,000-year-old very deeply buried pits and ephemeral pit structures dating to the Silverbell Interval have been found. Some of these features contained maize fragments.

A Silverbell Interval house encountered during the Rio Nuevo excavations south of West Congress Street.

During the following San Pedro phase (1200-800 BC), people developed very large field systems north of downtown in the area around West Ina Road and Interstate 10. People lived in small villages, perhaps seasonally, growing maize and storing the crop for consumption or for seeds for the next season’s crops. These people made baskets, textiles, and carved wooden household items that are not preserved in the archaeological record, although the stone tools used to make them are. Until recently, no features from this time span had been found in the downtown area. This year, fieldwork on the floodplain just to the southwest of downtown documented a pit that contained a San Pedro point, as well as two other pits containing maize fragments that dated to 1260-1004 BC.

A pit containing a large basin metate that was re-used as a mortar. The pit was radiocarbon dated to the San Pedro phase.

In contrast, five Early Agricultural period pit structures have been located downtown. Three were encountered during excavations prior to the construction of the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson museum. One of them, radiocarbon dated to the Early Cienega phase (800 to 400 BC), was stabilized and can be viewed at the museum. The other two pit structures were encountered during work the Joint Court Project and date to about 200 to 160 BC, during the Late Cienega phase (400 BC-AD 50).

Plan view map of an Early Cienega phase pit structure. This house is on exhibit at the Presidio museum.

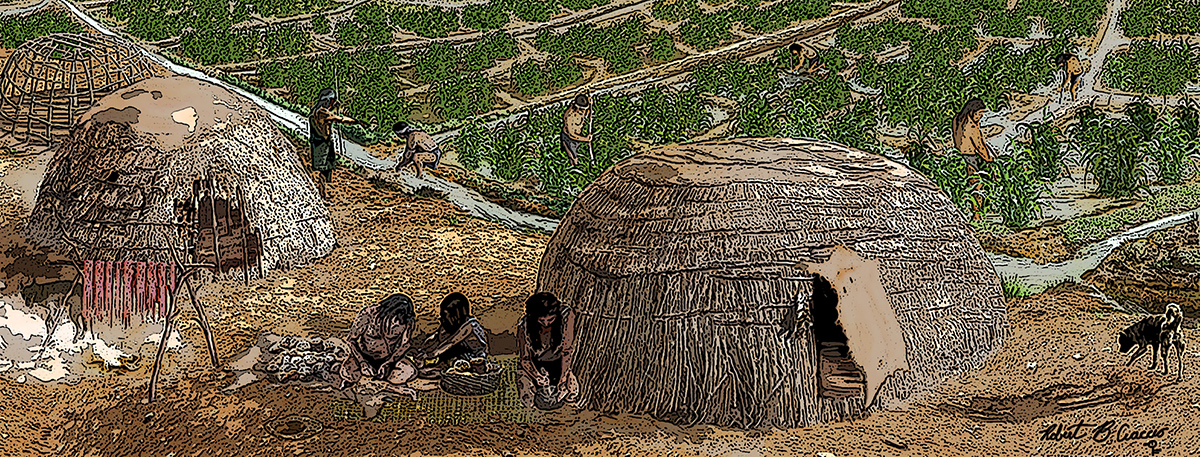

People continued to grow maize in irrigated fields on the floodplain during the Cienega phase. Most houses from this time were situated on the terrace close to the fields. People may have chosen to build on the terrace above the floodplain for several reasons: to avoid the occasional flooding of the river, to avoid using valuable field land, or—because the terrace slopes downward toward the floodplain—to allow people to watch over their fields. People continued to hunt the rabbits and rodents that ventured into their fields, and traveled away from their villages to hunt upland animals and to gather wild plants, but the evidence suggests that settlements were becoming more permanent and that farming was becoming more important.

The Early Ceramic period (AD 50-500), was marked by people developing ceramic technology to make pottery vessels, at first for food and crop storage, and later for cooking and serving foods and beverages. Only one possible Early Ceramic period feature, a small pit, has been documented so far in the downtown area. The other features from this time span that are nearest downtown are habitation and storage structures at the Mission Garden, close to the base of Sentinel Peak (also called “A” Mountain).

The Hohokam era in the Tucson area began around AD 500 and lasted until AD 1450. The Hohokam are well known for the pottery they created, which often incorporated elaborate painted designs. These designs changed every few decades, similar to how clothing styles change today. Through the excavation of stratified deposits and the use of radiocarbon dating, pottery experts can date the designs to relatively short time spans.

Hohokam pottery encountered during the excavations at the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson museum.

The Hohokam features encountered downtown range in date from the Tortolita phase of the Hohokam Pioneer period (AD 500-700) to the Middle Rincon phase of the Sedentary period (AD 1000-1100). The features include pit structures, pits, soil mining areas, and inhumation funerary features. During this time, many Hohokam communities built oval ball courts that were used for playing a special ball game and other ceremonies, bringing people from different communities together to trade and probably to find spouses. It is likely that a ball court once existed downtown, and perhaps someday one will be encountered.

Hohokam pit structure found beneath the south room of the Siqueiros-Jacome House at the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson museum.

Signs of Ancestral settlement continue to emerge in the downtown area. Recent work around the Historic (1929) Pima County Courthouse resulted in the location of three pit structures, two west of the courthouse and one beneath the intersection of North Church Avenue and West Alameda Street, as well as a pit, containing a broken plainware jar, that lay just beneath the curb on the south side of Alameda Street. These and the other encounters suggest that despite hundreds of years of construction and demolition in downtown Tucson, many more pre-contact features likely are preserved beneath the streets and sidewalks.