1820s Tucson: Life in a Mexican Frontier Town at the Time of Independence

Homer Thiel recounts some of the upheavals that affected life in Tucson at the time of Mexican independence.

This year, 2021, marks the 200th anniversary of Mexican Independence from Spain, which took place in September 1821. Tucson was on the northern Mexican frontier at the time, with three small communities in the Tucson Basin probably totaling fewer than 1,000 inhabitants.

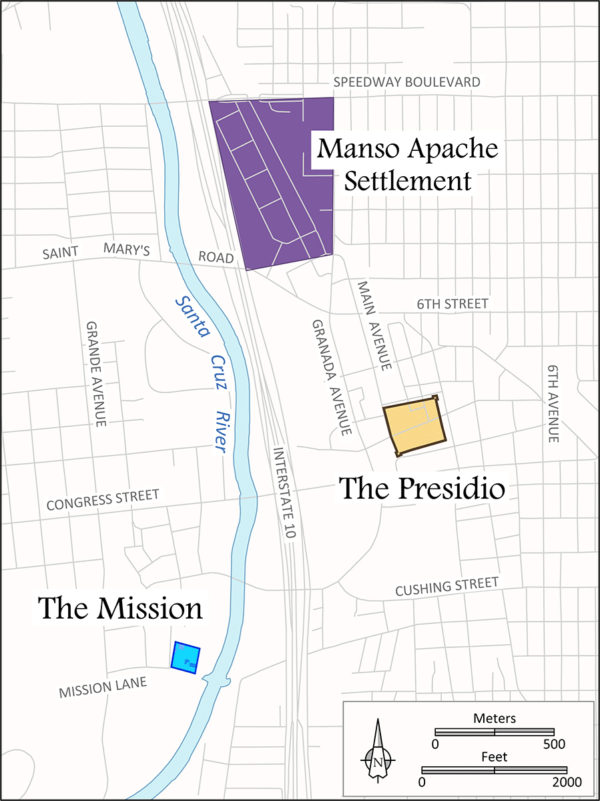

The Presidio San Agustín del Tucson was established in 1775 on the eastern terrace overlooking the Santa Cruz River floodplain. About 400 to 450 people lived inside the Presidio. About 100 Spanish soldiers were usually stationed there, but from the mid-1810s, dozens of soldiers had been sent south to fight the Mexican insurgents seeking freedom from Spain. The rest of the population included the wives, children, and servants of soldiers, as well as civilian families. Out on the floodplain sat the San Agustín Mission, at the base of a small mountain that today is known as Sentinel Peak or “A” Mountain. O’odham and Pima people lived at the Mission site. By the 1820s, only a small number of people remained there, the Native population dropping as people died from Old World diseases and moved onto other communities. Northwest of the Presidio, north of the Mission, was an Apache settlement that started in 1792. Little information survives on these people, who were given food, agricultural tools, and cloth by the Spaniards in exchange for remaining peaceful.

Map showing the locations of the Presidio, San Agustín Mission, and an Apache settlement in early 19th century Tucson (graphic by Catherine Gilman).

What happened here in the 1820s? 1820 saw the death of Capellan Pedro Antonio de Arriquibar, who had been the Presidio chaplain since 1797. He was a native of the Spanish Basque town of Zeanuri, baptized there in 1745. He joined the Franciscan order and traveled to Mexico in 1770. After working in California and Sonora, he arrived in Tucson in 1797. During the 23 years in office he was able to furnish the Presidio’s chapel with paintings, statues, and luxurious fabrics, all while recording baptisms, burials, and marriages in now-lost books. He drafted a will before his death, the document including an inventory of his estate, his two-room house located just outside the main gate of the fortress. His heir was Teodoro Ramirez, who on January 7, 1821, married his cousin Serafina Quixada after receiving special permission from the Catholic Church. Arriquibar’s successor as capellan was Juan Vano, who was in turn replaced by Father Rafael Diaz in 1824.

Father Arriquibar probably handed out religious medals similar to this to members of his congregation. This is the obverse side of a crucifix that would have hung at the end of a rosary. Imported from Europe, it is stamped with an image of the Virgin Mary, with the words VIR[GO] IMM[ACULATA] PURAM (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

In June 1823, Captain Jose de Romero of the Presidio led a group of Mexican soldiers to establish a mail route to California. It took several weeks for the party to reach their destination.

On December 19, 1824 the men of Tucson gathered to vote for the first civilian mayor of Tucson. Jose Leon took office on the first of January, 1825. He prepared a report on his first month in office, noting an attempted Apache raid on the livestock herd, a contentious footrace involving local residents and the Apache, and an attempted rustling of a cow and calf at San Xavier by a pair of soldiers and a pair of settlers.

Vessels created by local Native Americans, the O’odham and Pima peoples, were used for cooking soups and stews by Presidio residents (photo by Homer Thiel).

In 1826, a group of Gila Pima arrived at the Presidio to report that 16 United States citizens had visited them on the Gila River. The men had mules carrying trapping gear, planning to trap beaver. On December 31st, three of these men came to the Presidio, where they met with the Presidio mayor, Juan Romero.

In 1827, fears of an attack by another Native American group, the Yaqui, led to the repair of the Presidio walls, which had fallen down in several places. The following year saw the civilian residents of Tucson unhappy with reduced support from the Mexican government. It was difficult to grow enough grain to feed the population, because of increased Apache raids and also because the few remaining Mission residents controlled the water needed to irrigate fields. In 1828, the Mexican government expelled all foreign-born priests, including men stationed south of Tucson at San Xavier del Bac and Tumacacori. There would be no permanent priests in Arizona for another 30 years. Also that year, Teodoro Ramirez purchased land granted to the Apache, in what is today Barrio Anita. He paid two muskets, four zarapes, a horse, 16 pesos worth of tobacco, and 10 pesos to be used to purchase tobacco.

Majolica vessels were imported from the Mexico City and appeared on the tables of Tucson houses (photo by Homer Thiel).

The late 1820s saw the discovery of two large meteorites in the Santa Rita Mountains. These were brought north to Tucson, where the Pacheco brothers used them as anvils in their blacksmith shops. Today they are housed in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

The ring meteorite once stood outside the Pacheco blacksmith shop next to the Presidio’s main gate (Bartlett 1854).

Tucson survived the turbulent 1820s. A few years later, the 1831 census lists 465 people living in the town, many of them the ancestors of today’s Tucsonans.

Resources

Some sources to learn more about Tucson’s history:

John R. Bartlett, Personal Narrative of Explorations and Incidents in Texas, New Mexico, California, Sonora, and Chihuahua Connected with the United States and Mexican Boundary Commission, during the Years 1850, ’51, ’52, and ‘53. 2 vols. (1854), D. Appleton, New York.

Kieran McCarty, A Frontier Documentary, Sonora and Tucson, 1821-1848, (1997), University of Arizona, Tucson.

James E. Officer, Hispanic Arizona, 1536-1856 (1989), University of Arizona Press, Tucson (available in the Presidio Museum gift shop).

Victor T Stoner, Fray Pedro de Arriquivar, Chaplain of the Royal Fort at Tucson, Arizona and the West, Vol. 1(1), (1959), page 72.

Richard Willey, The Tucson Meteorites: Their History from Frontier Arizona to the Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution Press, (1987) Washington, DC.