E. J. Smith: Tucson’s First Professional Undertaker

During the Presidio (1775-1856) and early Territorial (1856-early 1900s) periods, family members and friends cared for the bodies of deceased people in Tucson. Local carpenters nailed together coffins, sometimes decorating them with paint and fabric. Religious leaders or friends conducted the funeral, and then the bodies were buried in the Presidio Cemetery (circa 1776-early 1850s), the National Cemetery (circa early 1850s-1875), and the Court Street Cemetery (1875-1909). The 19th century was a time period when treatment of the dead became increasingly elaborate. In Tucson, the arrival of undertaker E. J. Smith in 1878 led to more formal, memorable, and expensive funerals for residents of Tucson.

Smith’s origins are enigmatic, in part because of his extremely common last name. His first name was listed as Elbert on the 1860 census and Edward John in an 1883 newspaper article. In every other record he was listed as E. J. Smith. He was born about 1824 or 1825, in either New York or Louisiana (census records report both). He was a ‘49er to California. In 1852, he worked as a miner in Calaveras County. In 1854, he was a member of the Mountain Shade Lodge No. 18 of the Masons in Downieville, California, and by May 1856 was living in Sacramento. In July 1857, Smith advertised that he was selling a two-third interest in a steam saw mill situated on Wolf Creek near Downieville. He likely had some training in carpentry and cabinet making, either before arriving in California, or while he was there.

Later that year, in December 1857, he sailed to Hawaii. He initially worked at a variety of occupations, including as a butcher, while also serving in a militia that was formed in hopes of taking over the island from the Hawaiian royal family. In October 1858 he advertised his services as an undertaker and cabinet maker: “Begs Leave to notify the public that he is now prepared to furnish all kinds of coffins, and superintend Funerals, at the shortest notice. From the long experience he has had in the business, he trusts that he may give satisfaction to those who will favor him with a call. Ready made pine coffins always on hand, from $4 to $10; cherry and koa do., varnished, $10 and $25; koa do, polished, $25 and $40. Koa Lumber on hand and for sale at his shop, King street, nearly opposite the Seaman’s Bethel. N.B.- Furniture made, repaired and varnished, with neatness and dispatch.”

Smith’s advertisement in the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, October 14, 1858.

Hawaiian koa wood, offered by E. J. Smith as an option for coffin construction.

Smith’s sojourn in Hawaii was relatively short, and he sailed back to California in January 1860. He was in Marysville, north of Sacramento, in May 1861. By 1866 he was in Cauca, Columbia, where he undertook placer mining in a stream and found several prehistoric gold wire fish hooks. These would later be described in a Smithsonian Institution publication in 1885. He returned to the California and was married around 1868 to a woman named Mary Jane, a native of Ireland.

By 1870 the couple lived with their young sons Edward and George in San Diego, where E. J. was once again working as an undertaker.

Within a few years Smith had moved east to Yuma, Arizona Territory, where he was elected to the office of Coroner in 1874. In that position, he investigated unusual deaths and buried indigent individuals for the county. He moved briefly to Florence before settling in Tucson in the fall of 1878, where he opened an undertaking parlor.

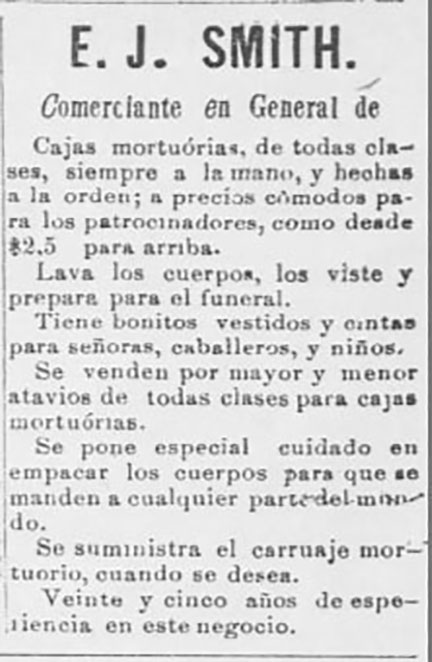

Advertisement for E. J. Smith’s undertaking services, Arizona Daily Star, June 27, 1880.

Shortly after the railroad arrived in Tucson in 1880 he had a hearse shipped in, but, unfortunately, the $1,200 conveyance was destroyed in a train accident. The 1880 census lists E. J. and Mary and their five children (Edward, George, Dan, Anna, and Virginia) living in Tucson.

Smith advertised his services in both the English and Spanish language newspapers in Tucson.

Spanish-language advertisement for Smith’s undertaking services, El Fronterizo, February 17, 1882.

His undertaking parlor was located at 403 Congress Street, currently the location of the U.S. District Courthouse. A local newspaper article praised his work: “The body of Dr. R. Gunn has been beautifully embalmed by Mr. E. J. Smith. Every embalmer always claims his process is a great secret, and Mr. Smith is no exception to the rule. Still the body as viewed this afternoon is certainly well preserved. The features look natural, and the skin has a marble-like appearance and the body is hardening and will continue so till it gets to be like rock. This modern science achieves something which nature did for the body of Washington.”

As an undertaker, Smith would go to the deceased’s home (and after 1879, perhaps to St. Mary’s Hospital) and retrieve the body with his horse-drawn wagon. At his undertaking parlor, the body would be washed. In cases where embalming took place, the blood and other bodily fluids were drained and embalming fluid was pumped in.

The body would be dressed, perhaps in a robe sold by Smith. The hair was styled, makeup might have been applied to improve the appearance of the departed, and then the body was placed into the coffin. Families could choose from a variety of coffins, ranging from inexpensive wood models to heavy metal caskets. Some had cloth lining with a mattress and pillow. Others were painted on their exterior. A variety of metal hardware was used to hinge, close, and lock the lid in place, along with handles to lift the lid and attached along the side to allow the coffin to be carried. Decorative hardware might be attached to the outside of the coffin, including religious ornaments such as crosses and crucifixes. Other decorations might include plaques with sayings including “At Rest.”

E. J. Smith’s funeral bill for S. C. Whipple, May 1880. The velvet covered coffin and trimming cost $55, the case for coffin $8, digging grave $4, ½ dozen gloves $2, three yards crepe $2. Total, $71.

The body and coffin were displayed during viewing, and after the funeral were carried to the burial plots in what became known as the Court Street Cemetery. Many of the graves had wooden vault boxes with lids that were put in place after the coffin was lowered in, protecting the expensive coffin–at least temporarily. Many grave markers at this time were made of wood. Those who could afford it might order a stone monument from Los Angeles, until tombstone carvers eventually opened businesses in Tucson. The undertaker also provided black cloth arm bands and hat ribbons for the mourners, and black gloves for the pallbearers. Altogether, Smith and the undertakers who followed him dramatically changed the rituals associated with death in Tucson.

In 1883, Smith bid on and received the contract for burying Pima County’s indigent dead: $9 for a plain coffin, $14 for burying within the city limits, and $16 for burying someone who died at St. Mary’s Hospital. In 1883, Smith was among a group of men who gathered to form a Knights Templar fraternal group, serving as treasurer in October 1886. He was also a member of Pima Lodge No. 3 of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, where he served as “Past Grand.” After serving as Coroner in 1884 and 1885, Smith sold his business in August 1886: “Undertaker E. J. Smith has sold out his stock of coffins, caskets, etc., and the good will of the business to Sam Baird, who is now the only undertaker in the city.” His sons operated a new business beginning in October 1886 and were still burying indigent dead in April 1890.

Smith eventually left Tucson. In late December 1898, a newspaper printed his death notice: “Of late he had been traveling through the eastern and southern states and his death was the result of pneumonia. He had recovered from the attack and was up and around when a relapse set in which ended in his death.” Ironically, along with the exact place and date of his death, the burial place of E. J. Smith is unknown.