The Broken and the Whole: Cruciforms in the Tucson Basin

Desert Archaeology’s ground stone analysts, Dr. Jenny Adams and Tessa Branyan, discuss a rare Early Agricultural period artifact type.

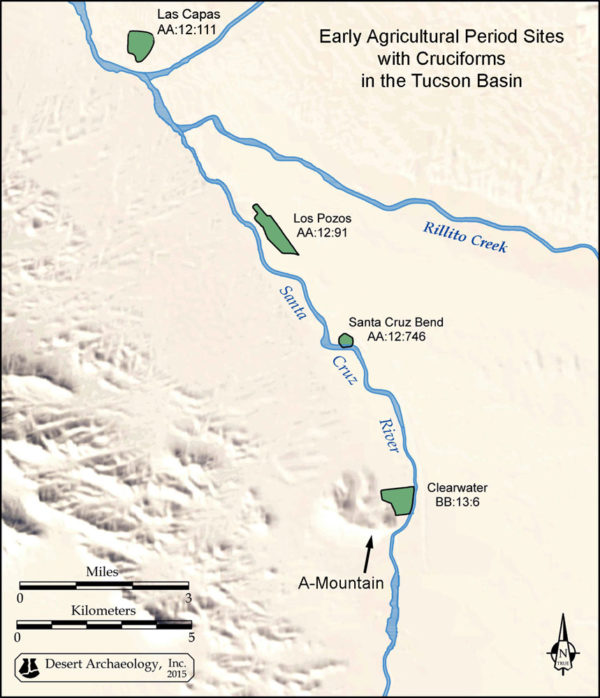

What do the Las Capas, Los Pozos, Santa Cruz Bend, and Clearwater sites have in common, besides the fact that people lived in these settlements along the Santa Cruz River during the Early Agricultural period (1200 BC-AD 50)? Think rare ground stone artifacts–think cruciforms!

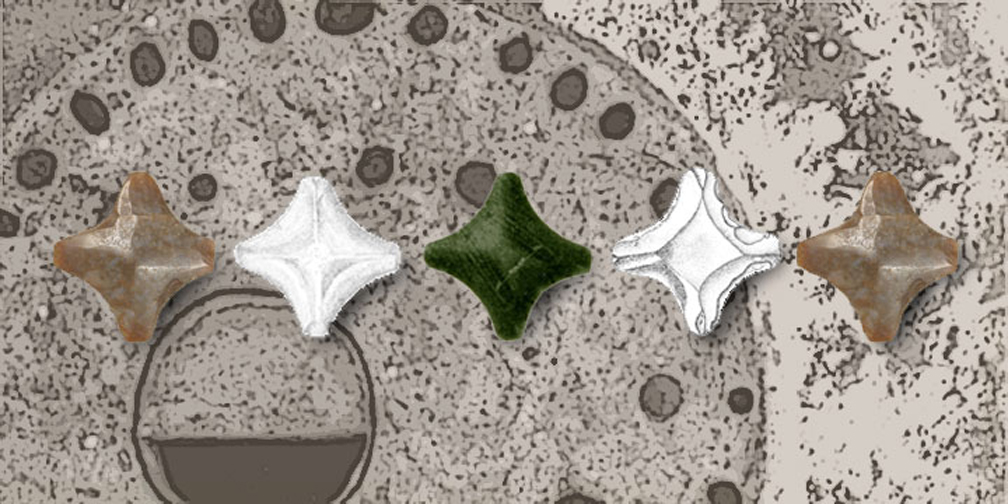

Cruciforms are symmetrical, highly polished, cross-shaped objects with four short tines that are oriented at 90-degree angles. They typically are made from cryptocrystalline rocks (such as chalcedony and jasper), obsidian, or dense volcanic stone.

Cruciforms have a limited geographic distribution within the southern U.S. Southwest and north-central Mexico. Since the early twentieth century, roughly four hundred cruciforms in total have been recorded in central-southern Arizona, near the southwestern border of Texas, and in northern Sonora and Chihuahua, Mexico. A majority of these were found in contexts pre-dating the development of ceramics. In the Tucson area, they have been found in Early Agricultural period sites along the Santa Cruz River.

The oldest, at Las Capas, date to the Late San Pedro phase (1000-800 BC). The latest are from Los Pozos, dating to the Late Cienega phase (400 BC-AD 50). As far as we know, no cruciforms have been recovered from Hohokam or other post-AD 50 contexts. Although whole cruciforms were recovered from Hodges site (primarily Hohokam) and the Presidio San Agustín (primarily Historic era), both sites contain Early Agricultural period components.

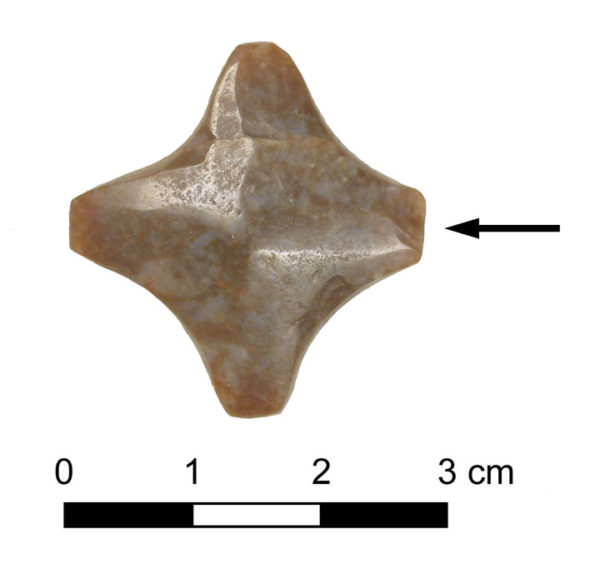

With the discovery of a nearly whole cruciform in the upper fill of a Cienega phase pithouse this summer, during Desert Archaeology’s most recent excavations at the Clearwater site, the count is now 10 cruciforms from Tucson Basin Early Agricultural period sites.

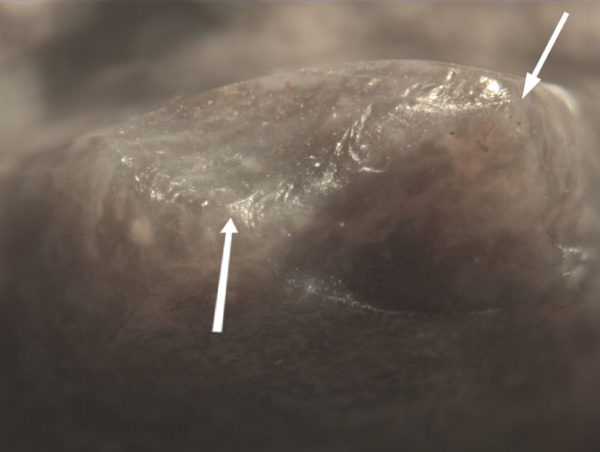

Cruciform found at the Clearwater site. Abraded and polished with some of the manufacturing facets still visible. The removal of two flakes from one tine, at arrow, may reflect ritual destruction.

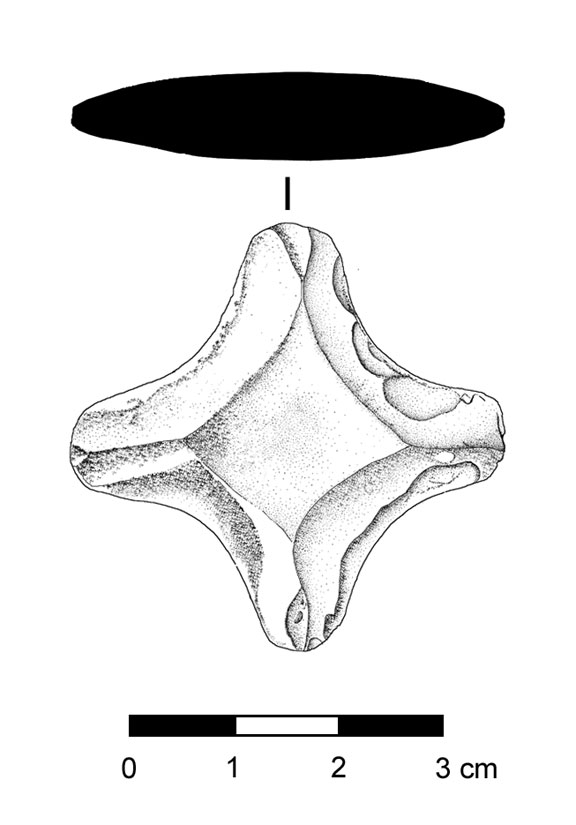

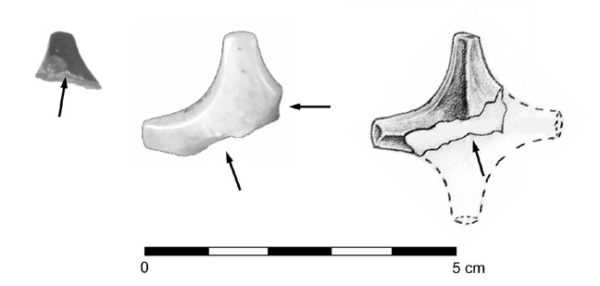

A cruciform found in a mortuary feature containing the remains of an adult male during earlier investigations at Clearwater is whole, symmetrical, and polished, but with remnant flake scars that indicate it was shaped through flaking before being ground into its final form.

Whole cruciform buried with an adult male at Clearwater. Manufactured from chalcedony with flake scars and facets still visible. Illustration by Rob Ciaccio.

The most perfect cruciform yet found during a Desert Archaeology excavation was made from a clear quartz crystal and polished to the point that no flake scars remain visible. This piece, along with a broken one, were in the upper fill of a pithouse at Los Pozos.

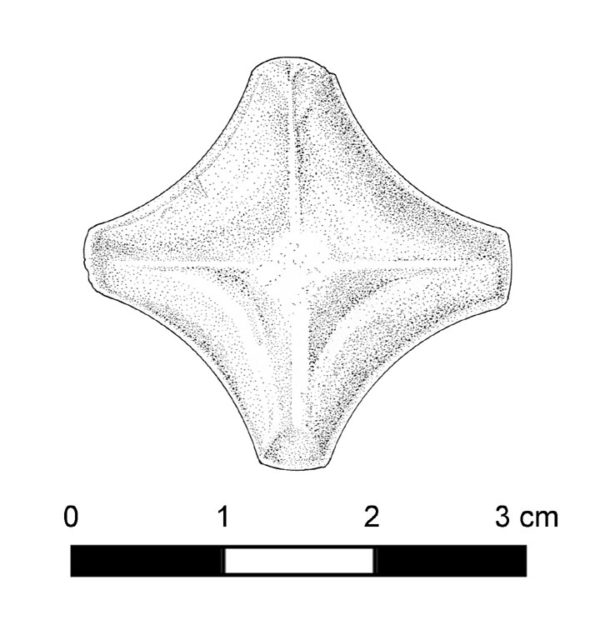

Whole cruciform made from a clear quartz crystal found at Los Pozos, polished to the point that no manufacture attributes remain. Illustration by Rob Ciaccio.

Two more whole cruciforms were in found in different floor pits within this structure. Other broken cruciforms were found in pithouse fill at Las Capas and the Santa Cruz Bend site.

There is evidence that cruciforms were intentionally broken. A closer look at the newly recovered piece from Clearwater revealed that it was intentionally broken, as two flakes were struck from different directions on one of the tines.

Photomicrograph (20x magnification) of the broken tine on the Clearwater cruciform pictured at the beginning of this post, showing flake scars. Arrows indicate directions of flake removals.

Impact fractures and flake scars remain where a hammerstone was used to break the tines off the bodies of three cruciforms from Las Capas.

Three broken cruciforms found at Las Capas. Each one was destroyed by the stroke of a hammerstone (at arrows). Two are highly polished mudstone and the other white chalcedony.

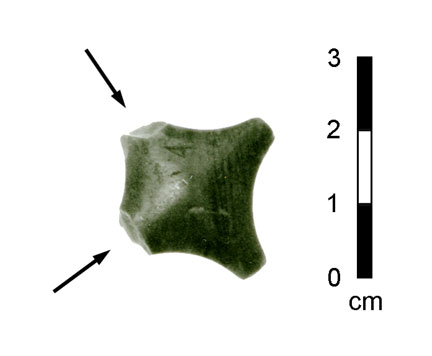

Finally, the cruciform from Santa Cruz Bend is missing two of its tines.

Cruciform from Santa Cruz Bend with two tines flaked off the body, at arrows. The cruciform was made from jasper and thoroughly polished, removing all signs of the flake scars left during manufacture.

Why did people break these artifacts, which took considerable time and effort to manufacture? Our thinking is that such intentional acts of destruction were probably powerful behaviors that had meaning to the person breaking the object and to anyone witnessing the destruction. Once broken, the meaning or power inherent to the object was released, and the pieces were disposed of as everyday trash, tossed with other refuse into abandoned pithouses. In contrast, the more rare whole cruciforms were placed in a funerary feature and in floor pits, with only one found in general pithouse fill. This suggests that whole cruciforms were treated differently than the broken ones. Whatever the cruciforms symbolized to the Early Agricultural period people, their importance was not recognized by the Hohokam.