Downtown Historical Archaeology: The Tucson Sampling Works

Homer Thiel tells the story of a 19th-century ore assayer whose office was unearthed during archaeological work near the historic train depot in downtown Tucson.

Arizona has long been marketed as the land of “5 Cs”:Climate, Cattle, Cotton, Citrus, and Copper. In the last quarter of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, large numbers of people made their income from these five industries. Among them was Charles Wores. Charles was born in 1859 in California, the son of an immigrant couple. His father worked as a hat manufacturer in San Francisco, where Charles received an education. His brother Theodore Wores would go on to a distinguished career as a portrait painter.

Charles moved to Arizona in 1880 and became involved in mining in the southern part of the territory. The industry was going through boom times in the region. Hostilities with the Apache had dramatically declined, allowing prospectors and miners access to the mountains where they found copper, silver, and gold ore. The arrival of the Southern Pacific railroad in the same year allowed ore to be shipped out of the Arizona Territory to be processed, or processed ores to be sent to factories in the American Midwest. Prospectors and miners needed to know the quality of their ore, and so by 1882 Charles opened an assay office in Tucson. Wores moved his office to near the Southern Pacific Depot in 1887, allowing ore to be easily transported to his business.

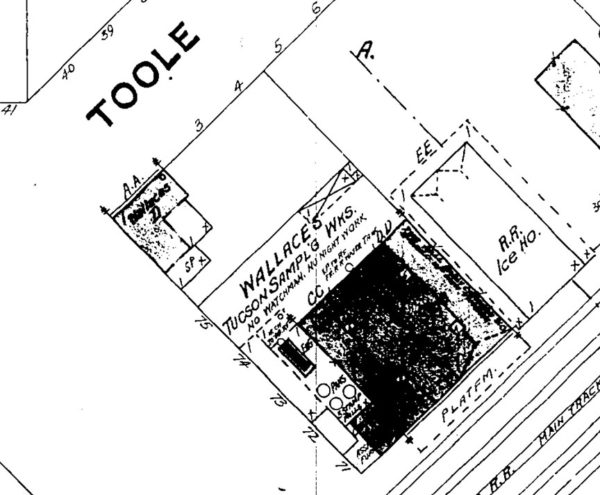

The 1896 Sanborn Fire Insurance map mistakenly labeled the Works as Wallace’s Tucson Sampling Works, perhaps because Charles Wores had a German accent.

Desert Archaeology uncovered the remains of this business, the Tucson Sampling Works, in 2009 prior to the construction of a large building that now houses the Plaza Centro parking garage and apartments on Congress Street in downtown Tucson. We found the adobe walls of the Sampling Works, machinery mounts, and large pits filled with pale green soil. At first we thought these were outhouse pits, but after digging into one we found numerous pieces of assaying equipment—cupels, scorifiers, and crucibles. We realized that the soil in the pits was probably dangerous and stopped excavating them. Later, the City of Tucson tested the soil and found it contained a high amount of hazardous waste.

Cupels are made from bone ash pressed into a mold. They were used to extract silver and gold from other metals, and through careful weighing the amount contained in a sample could be determined. Sample numbers, written in pencil, were visible on many (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

Scorifiers were used to extract silver from samples weighing less than five grams. Heated in an oven, the assayer would observe the sample through a window and pour off the silver when a ring of slag formed in the small vessel (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

Crucibles were used for processing larger ore samples. The thick walls could withstand high temperatures (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

Wores lived in an adobe house on the property, and we found a pair of outhouse pits associated with Wores’s occupation. One was 1.75 m deep and yielded a decorated O’odham olla, a Mexican ceramic duck, tin cans, and cupels.

The second contained bottles, dishes, a chamber pot lid, a pocket watch, a pencil lead, and yet more cupels (altogether, we found more than 250 of these). Food remains found in the pits reveals that Wores purchased mostly high quality, expensive cuts of meat and may have entertained guests at his home.

When not at work, Charles obtained a large mineral collection. In 1884, it was displayed at the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exhibition in New Orleans. He served in the 14th Territorial Legislature in 1887, introducing a bill to regulate dentistry, which passed the House but failed to be voted on. In June 1893, Charles and John V. Wilson applied for a United States patent for a salve based on Encelia farinose, or brittlebush. The claimed their concoction was useful for healing “pimples, boils, and similar ailments.” The pair never commercially manufactured the substance.

Wores continued operating the assay business until about 1901. The works were torn down and the Southern Pacific built a clubhouse on the property, in an attempt to lure its workers away from businesses like the Cactus Saloon, which operated across the street. Afterward he moved to California and took up farming, a profession he followed until his death on December 12, 1929.

Resources

This archaeological work was funded by the City of Tucson in compliance with local and state historic preservation statutes. The city has made the report from the excavations available as a free PDF.