Mexican Fortress to US Town: Tucson in the 1840s and 1850s

Homer Thiel winds the history machine back a few decades from the previous posts to look at life in Tucson during the time of transition from Mexican to US governance.

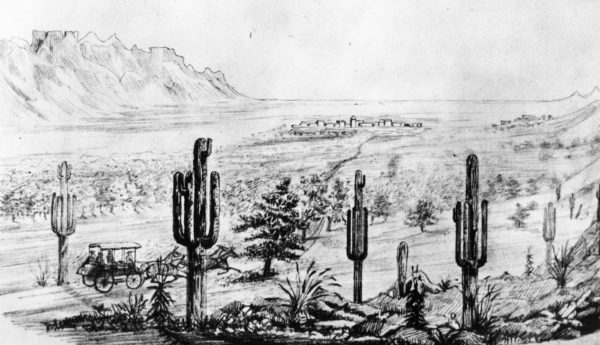

Mexico achieved independence from Spain in 1821. In the years afterward, many changes occurred in the small fortress community of Presidio San Agustín del Tucson. The 1840s were an especially trying time for its residents. The Spaniards had maintained a force of about 100 soldiers at the fort, but the Mexican government lacked the immense financial resources of the Spanish Empire. As a result, the number of soldiers was reduced to about 60. This took place while Apache raids in the region were intensifying. Gradually the other settlements in what is now southern Arizona were abandoned, the people leaving missions, ranches, and mines and either heading south into Sonora or moving to Tucson, which by the late 1840s was the only community left.

Native Americans brought firewood, fodder, wild game, and pottery to trade with the residents of the Presidio (mural at the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson Museum).

To the west of the Presidio, the San Agustín Mission—the birthplace of Tucson, located on the banks of the Santa Cruz River—was also abandoned, the roof of its chapel collapsing. In 1850, the fields around the mission were described in Noticias Estadísticas del Estado de Sonora: “In the few lands that are cultivated, all kinds of grains are reproduced, that is, wheat, beans, chickpeas, lentils and corn, all of excellent quality and in great abundance. There are also orchards with lots of quince, peaches, pears, apples, apricots, and plenty of vines.” As the population of Tucson expanded and required more food than the area around the fortress could supply, residents of the Presidio appropriated the mission fields. Farmers traveled here, guarded by soldiers, to plant and harvest crops.

In mid-December 1846 the Mormon Battalion visited Tucson. This was a group of over 500 Latter-Day Saints adherents who were tasked by the United States government to march from Iowa to San Diego, California. Prior to their arrival, most residents of the community fled south to San Xavier del Bac. Those that remained traded with the soldiers, offering food for items of clothing. The soldiers were told to behave but were allowed to appropriate some wheat from the community’s warehouse.

A statue depicting members of the Mormon Battalion trading with Teodoro Ramirez (Clyde Ross Morgan, 1996).

Many of the Mormon men kept diaries. Henry W. Bigler wrote: “This place is called Tucson and is nothing but a Mexican outpost against Indians. It looked good to see young green wheat patches and fruit trees and to see hogs and fowls running about and it was music to our ears to hear the crowing of the cocks. Here are the finest quinces I ever saw…In the place are 2 little mills for grinding grain and run by jackass power, the upper millstone moved around as fast as Mr. Donkey pleased to walk.” The donkey-powered grain mills impressed several other men, who had seen nothing like that before. They did not talk about the communal ovens, where loaves of bread were quickly baked.

The community lacked a resident priest because all foreign-born priests had been expelled from Mexico in 1828. Between 1844 and 1848, a priest from Magdalena traveled through the region, performing baptisms and recording the events in church records. People may have journeyed south to Sonora to be married. Funerals were conducted by family members and friends with the bodies interred in the crowded, consecrated burial ground of the Presidial chapel.

A census taken in early 1848 lists 509 residents living at the Presidio. Among these individuals were 17 soldiers who were ambushed by Apache warriors and killed in the Mustang Mountains, southeast of Tucson, in May 1848. Afterwards nine widows petitioned the Mexican government for money and clothing.

As if that weren’t bad enough, in 1851, 122 residents of Tucson died—mostly from cholera—with only 19 children being born. The large number of deaths likely spurred the creation of a new consecrated burial ground northeast of the Presidio. Other residents may have left for California during the Gold Rush, which saw wagon trains passing through the community.

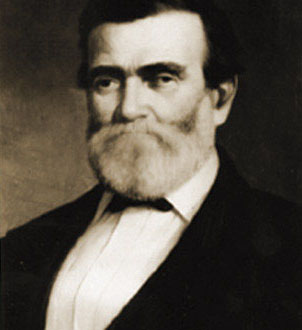

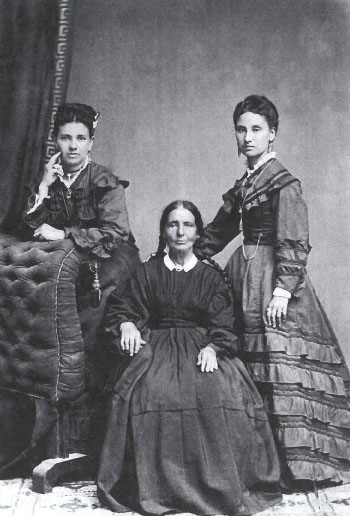

The United States acquired Arizona south of the Gila River through the Gadsden Purchase of 1853 (ratified in 1854). A small number of United States citizens soon began to arrive. One of the first was Solomon Warner, who brought a freight wagon train loaded with consumer goods to Tucson in February 1855. Another was a Swiss schoolteacher named John Spring. As the Mexican military made plans to leave the Presidio, Guadalupe Santa Cruz, a 48-year-old widow caring for two nieces, asked Spring whether it would be safe to remain. He told her yes. The Presidio commander packed up the fort’s records and headed south to Imuris, Sonora with his soldiers and their families. Many of the latter, including Francisco Solano Leon, would return to the community.

Solomon Warner worked as a saloon keeper, merchant, and mill owner in Tucson.

Guadalupe Santa Cruz and her nieces Atanacia and Petra, who she married off to wealthy newcomers.

Change came fast after 1856. The United States military set up camp in the community. The last Apache raid had been in 1852, and the arrival of the military made the region safer. Hundreds of people from the eastern United States, California, and Sonora moved to the area in search of economic opportunities. By 1860, there were 1,232 people living in Tucson. In 2020, the US Census recorded the city’s population as 542,629. Thousands of these people may be descendants of the hardy folks who lived in Tucson in the 1840s and 1850s.