Answering Archaeology Questions: Pithouse Architecture

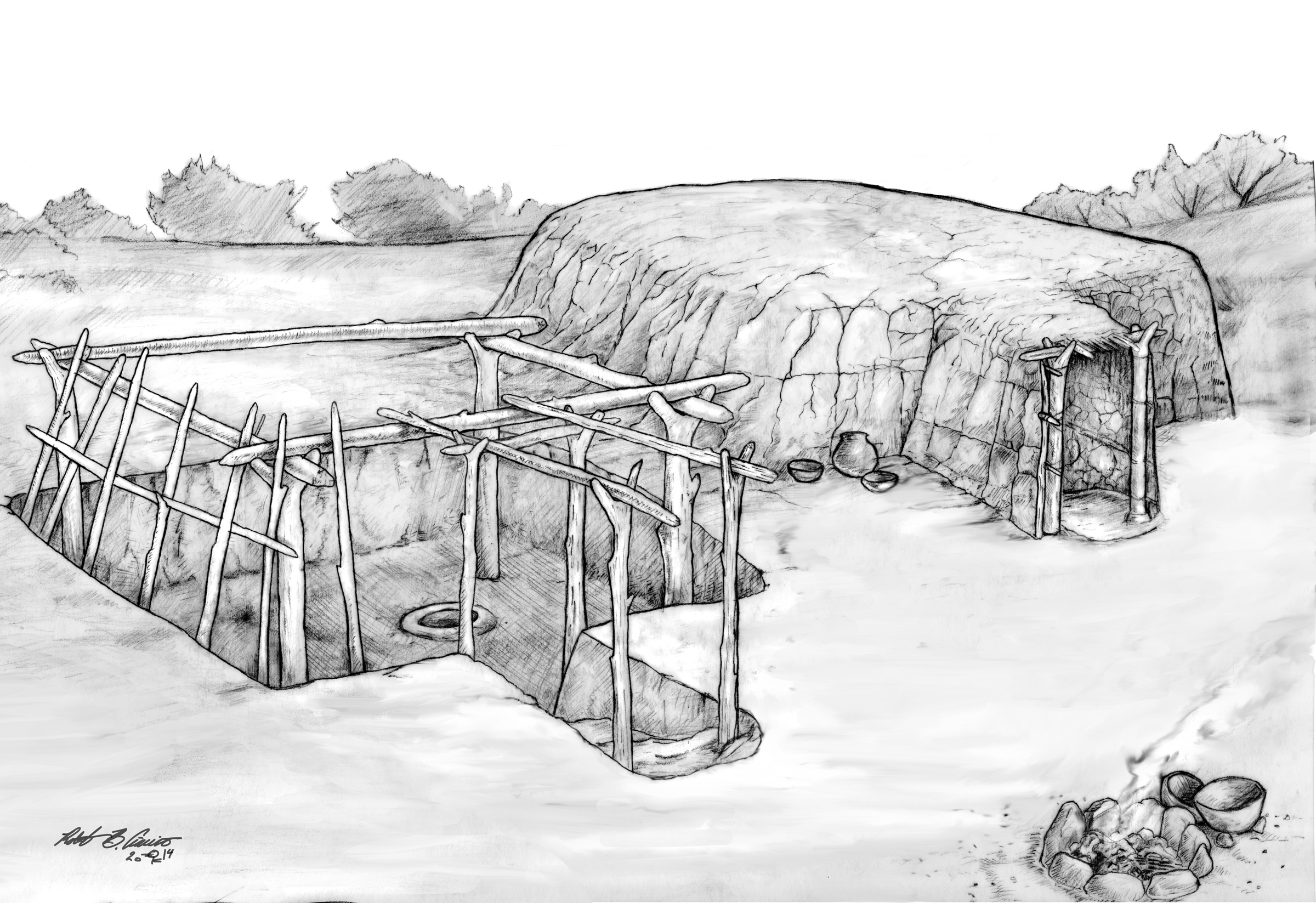

Homer Thiel explores pithouse architecture and how the most common prehistoric dwellings in southern Arizona changed over time. The illustration at the top is by Robert Ciaccio.

For several thousand years people have been constructing pithouses in the Sonoran Desert. Desert Archaeology employees are frequently asked “What is a pithouse?” and “How were they built?”

Pithouses, also called pit structures, were the most common form of Native American dwelling found in the Sonoran Desert from at least 4,000 years ago into the 1400s. The main attribute of pithouse architecture is a pit dug into the ground that forms the foundation of the house. Why dig a pit? Earth has insulating qualities and the sunken houses may have been warmer in the winter and cooler in the summer than surface structures. Archaeologists usually find these pits in backhoe trenches or by stripping away overburden. In either case, the pits are identified by the presence of charcoal-stained earth, by wall and floor plaster, or by the presence of trash. Archaeologists excavate pithouses to get samples of artifacts, animal bones, and plant remains and to study the house’s architectural attributes. The recovered artifacts can date the house and tell what types of activities took place inside it, while animal bones and plant material can reveal the diet of its occupants and the local environment surrounding it. Pithouses were used for dwellings, storage places, or ceremonial purposes.

Pithouse construction began with people digging a hole in the ground, probably using digging sticks, stone hoes, and baskets to loosen and remove the dirt and caliche (hard layers of naturally occurring calcium carbonate). The size, shape, and depth of the foundation pit varied through the years. Most Early Agricultural period (2100 B.C. to A.D. 50) structures are round. Early Ceramic period (A.D. 50 to 500) can be oval, rectangular, or square, each with an entryway projecting from one side. Hohokam period (A.D. 500 to 1450) houses are most often rectangular or subrectangular (with rounded corners), again with protruding entryways. During the Hohokam Classic period (A.D. 1150-1450), builders also began to construct above-ground adobe or masonry rooms, sometimes arranged in a row, while still creating pithouses.

After completing the pit, the builders then had to erect walls and a roof. During the Early Agricultural period, postholes were dug around the inside edge of the pit and small saplings were inserted, the soil tamped back down, and then the saplings were tied down to form a dome. A series of horizontal stringers were attached around the outside of the sapling poles. Then bundles of sticks, reed matting, and grass were used to cover the exterior of the house, which was coated with a layer of mud. The entrance into the house was probably an opening in the wall covered by an animal hide or a woven mat.

An Early Agricultural period (2100 B.C.-A.D. 50) house-in-pit style pithouse at the Mission locus of the Clearwater Site in Tucson, with a row of postholes around the inside edge of the pit (photograph by Homer Thiel).

A different Early Agricultural period pithouse at the Mission locus of the Clearwater Site burned. The charred wall poles and stringers found by archaeologists are visible on the floor (photograph by Gregory Whitney).

Early Ceramic and Hohokam period builders had two options for the walls of their houses. True pithouses used the wall of the pit as the wall of the house, setting the posts outside the pit, along the outside perimeter. These people often coated the floor and wall of the house with a plaster material, made by mixing water with dirt or ground-up caliche. In contrast, people building a house-in-pit dug postholes on the inside edge of the pit, often in a trench. Floors were again plastered and the wall interior might have been plastered or covered with woven mats.

A square Early Ceramic period (A.D. 50-500) house-in-pit structure at the Mission Garden locus of the Clearwater Site with postholes around the interior wall, a short protruding entryway in the foreground, and an intrusive roasting pit in the middle of the structure (photograph by Gregory Whitney).

A Hohokam house-in-pit structure with a wall trench, numerous postholes, and a polished caliche floor at the Hardy Site at Fort Lowell in Tucson (photograph by Jeffrey Charest).

In both situations, other postholes were cut into the floor in the middle of the house to help support the beams (vigas) that formed the roof of the house. The wall posts and roof beams were obtained from nearby mesquite and cottonwood trees, or from more distant pine trees carried or washed down from adjacent mountains.

The Hohokam covered the roof beams with smaller sticks (latillas), and then packed mud (daub) on top. Houses often burned and sometimes the daub would be hardened by exposure to heat, allowing archaeologists to see how the wall posts, roof beams, and latillas were arranged.

A fragment of fire-hardened daub bearing impressions of sticks used in the roof or wall of a pithouse at the Hardy Site at Fort Lowell (photograph by Homer Thiel).

Storage pits are sometimes present in the floor. Some Hohokam houses had raised platforms, perhaps for beds or for storage, around the back and side walls. A house recently excavated at the Pima Animal Care Center in Tucson had a set of small postholes arranged in a circle for a raised granary.

A Hohokam house-in-pit structure with a stepped entrance, wall trench, and ring of internal postholes for an elevated granary, found during Desert Archaeology’s work at the Pima Animal Care Center (photograph by Homer Thiel).

Entryways came in a variety of styles, some with sloping ramps, others with steps. Some houses have a set of molded adobe cones enclosing the posts placed at the point where the entrance joined the house walls. A plastered fire hearth is usually found just inside the entryway. It is likely that a small hole was present in the roof of each house to allow smoke to exit.

A Tortolita phase (A.D. 500-700) house-in-pit structure at the Pima Animal Care Center excavation in Tucson with an offset and stepped entrance, plastered hearth, and wall trench (photograph by Homer Thiel).

Perishable materials—wood, basketry, and textiles—rarely survive at open-air sites, so we know little about the types of furnishings once present inside houses. More durable items—manos and metates, pots, stone or bone tools, and shell jewelry—are often found, especially in houses that burned.

A Hohokam true pithouse, with plastered walls, stepped entrance, polished caliche floor, and numerous floor artifacts at the Hardy Site at Fort Lowell (photograph by Jeffrey Charest).

Pithouses were an enduring form chosen by the people who lived in the Sonoran Desert for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans, providing shelter from the sun and a snug dwelling during cooler seasons. Studying differences between sites and time periods in pithouse architecture, including house size, durability, and evidence for remodeling, helps us discern how long people stayed in one place, which seasons they spent there, and how they organized their settlements into family and social groups. Read more about pithouse construction at the links below.

Resources