Construction Monitoring: CRM Archaeology One Trench at a Time

R. J. Sliva gets out of the lab from time to time, trading the lithic analyst hat for a construction monitor’s hard hat and safety vest.

What do archaeologists do? The first answer that probably comes to mind is “Dig!” We do indeed spend a lot of time moving dirt with mattocks, shovels, trowels, and dental picks as we excavate sites to recover cultural data. Most people are not as familiar with archaeological construction monitoring, which involves us watching other people dig. This may not sound as exciting or glamorous as digging an entire prehistoric settlement or documenting life in historic Spanish fortresses, but monitoring is a vital service we provide when construction and utility crews disturb ground in archaeologically sensitive areas. In Tucson, that means most of downtown as well as the areas along the Santa Cruz River.

A small trackhoe excavates a trench for a waterline near an archaeological site in Tucson. (photo by RJ Sliva)

Under certain conditions, construction monitoring is one of the cultural resources management services we can provide to clients who are working on public land, in order to bring their projects into compliance with federal and state historic preservation laws. This option fulfills compliance requirements when ground disturbance will be limited, or when the construction project is in a setting that is already heavily developed, or as a precautionary measure due to nearby cultural resources. The monitor must be a trained archaeologist who stands by to observe as construction crews dig with either heavy equipment or hand tools, looking for any cultural features that may be encountered during the work.

An essential part of any monitoring job is giving the construction crew a quick briefing on the kinds of cultural resources that may be lurking underground, as the backhoe operator has the best vantage point and is often the first person to spot artifacts when the bucket comes up. Many of the workers I have spent time with on construction sites are interested in the history and prehistory lying underground—after all, they spend so much time working the dirt that they have seen quite a bit of it. Everyone is interested to see artifacts. No one wants to disturb a burial.

If the digging hits something that looks like a cultural feature, the monitor signals the construction crew to pause and then hops down into the trench or pit—via the OSHA-mandated ladders placed at regular intervals—and inspects the evidence. This might be a patch of darker soil within the usual light-colored desert deposits, a clump of glass bottles, or the profile of an oxidized roasting pit hanging in the side of a trench.

Sometimes differences in soil color turn out to be nothing.

The cream-colored band in the side of this trench caught the monitor’s eye, but turned out to be a caliche (naturally occurring calcium carbonate) deposit. (photo by RJ Sliva)

And sometimes they are indeed a cultural feature. If the feature contains human remains, all work in the vicinity stops immediately until the remains have been carefully and respectfully excavated so they may be repatriated to the appropriate descendant community for reburial elsewhere. If the feature does not contain human remains, the monitor determines whether the construction work will cause further damage to the resource. If not—for example, when a narrow utility trench cuts through a pithouse but will not have an impact on the parts of the house that are still intact on either side of the trench—the monitor records the location of the feature using a GPS unit, measures the linear extent of its exposure in the trench, takes photographs, and notes any artifacts in the removed dirt (or hanging out of the trench wall) that appear to be associated with it. Artifacts found in the backdirt or that otherwise lack a direct context are recorded and left in the field unless they are culturally and temporally diagnostic.

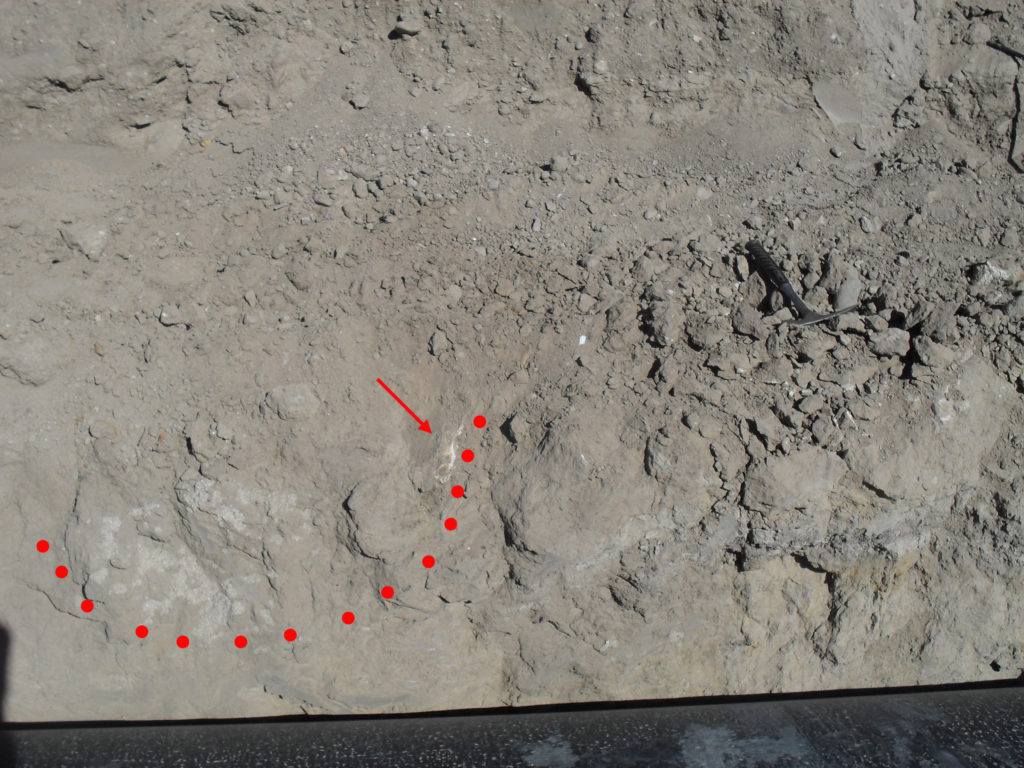

This backhoe trench cut through a pit (marked with red dots). The pit looked like it contained bone (red arrow). (photo by Greg Whitney)

If the construction activities will damage the cultural resource, as in the case of a wide trench or pit creating a considerable horizontal disturbance as well as a vertical one, work stops long enough to permit the archaeologist to excavate at least a portion of the feature. Typically, half of a non-mortuary pit will be excavated, while pithouses that are encountered have 1-by-2-meter test units dug into them, with additional excavation as warranted. These feature locations are also recorded via GPS, the feature dimensions are measured, and any artifacts are collected. Once the archaeological data recovery is finished, the construction can start up again.

Data forms on an iPad make quick work of recording the location, measurements, and notes from features encountered during monitoring, and allow rapid connection with both the database and analysts back at the office. (photo by RJ Sliva)

This was the case in late 2016 when a backhoe digging a trench for the installation of a pedestrian crossing at Fort Lowell Park in Tucson hit a Hohokam pithouse while Desert Archaeology’s Rob Ciaccio was monitoring construction. Because the installation needed to open up a fair amount of ground in an area that is known to contain dense prehistoric deposits, after the pithouse was encountered, a small crew came in to excavate the house and several adjacent pits. The finds were interesting enough to catch the attention of local news. Three days later, construction resumed and the traffic control device was installed without further incidents.

Some projects involve considerably more ground disturbance than a single utility trench. In 2015, Desert Archaeology monitored the removal of contaminated soil on a parcel of land acquired by the City of Tucson to expand Fort Lowell Park. When the soil was stripped away, our monitors found ten Hohokam pit structures that we subsequently excavated and recorded.

Hohokam pithouse encountered during construction monitoring at Ft. Lowell Park. Lying on the floor were a decorated jar, a spindle whorl, and 10 pieces of ground stone. (photo by Jeffrey Charest)

Construction monitoring is very much peering-through-your-fingers archaeology, with the narrowest of windows only briefly opened up into the past. There is also an element of hoping the backhoe doesn’t crash through a buried cultural feature, ripping out a two-foot wide section of something we will never get back. But that’s why we monitor, making sure that damage is minimized while working quickly to get construction back on track as soon as possible. It’s gratifying when the pipeline guys stop the backhoe with a chorus of shouts and jump into the trench to retrieve stray bones that they cradle and carefully pass up to me, even when they turn out to be not-very-old dog bones, or break into grins when they realize the piece of pottery they just pulled from the dirt is from a child’s tea set from the last century. Finding one more pit or one more pithouse near a site that’s already been dug isn’t redundant—it adds one more line to the tapestry of this place where people have lived for 4,000 years. Life goes on here and new waterlines have to be laid. We are there to monitor and document it.