Rabbit, Rabbit: The Small, Furry, and Fast Dietary Staple of Ancient Arizona

Desert Archaeology zooarchaeologist Jenny Waters teams with Homer Thiel this week to explore the go-to protein source for ancient inhabitants of the Sonoran Desert. Content advisory: this post contains a historic photograph of the aftermath of a jackrabbit hunt.

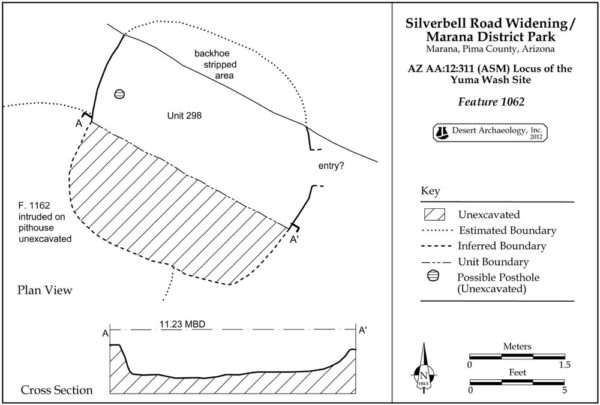

Ten years ago Desert Archaeology conducted excavations at a portion of the Yuma Wash Site, a large Hohokam habitation site located beneath what is now Silverbell Road in Marana. Feature 1062 was a Classic Period (AD 1300-1450) pit structure that was very unremarkable, with no interesting architecture, except that the archaeologists digging within the structure found an extremely dense layer of rabbit bone. Why were over 1,000 bones found in this relatively small area?

Cottontails and jackrabbits were the main meat source for the people living in the Tucson Basin for millennia. Their bones have been found in archaeological sites dating from the Early Agricultural period to historic-era trash in downtown Tucson. These two animals look alike, and many people think of them as just “rabbits,” but they actually have different behaviors and prefer different environmental conditions.

Cottontails like to hide from predators in closely spaced vegetative cover. Agricultural fields provide a perfect place for them, and as a result they were often hunted there by farmers protecting their crops. It is likely that one of the tasks given to Hohokam children was to guard fields and capture and kill cottontails using bow and arrows, snares, throwing sticks, and sling shots.

The larger jackrabbits prefer a more open environment because they use speed and agility to evade predators.

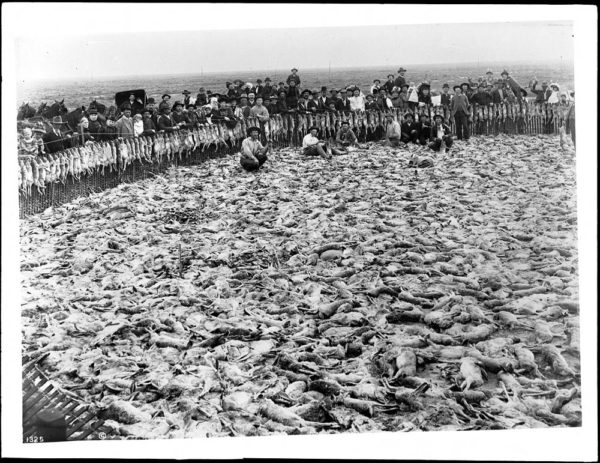

They were sometimes hunted in large numbers through “rabbit drives.” Evidence for this kind of jackrabbit hunting is identified at archaeological sites when we encounter features with unusually large amounts of rabbit bone. The presence of so many bones concentrated in one feature suggests a single event, such as the killing, butchering, and eating of many rabbits from a communal hunt.

Jackrabbit and cottontail bones excavated from an Early Agricultural feature at the Las Capas site. After bones are cleaned, Jenny Waters compares the bones to those in our comparative collection and enters the data into our faunal database.

Ethnographers in the past recorded communal hunting in the Southwest and noted that it often took place during other activities that required cooperation, such as building, repairing, and cleaning out irrigation ditches. Rabbit drives would provide a large supply of meat for feasting in a single hunting episode.

What a rabbit drive looks like. Photo not of a Native American hunt, but of a group of 7 Anglo hunters in a corral containing thousands of dead jack rabbits following a rabbit drive in which 20,000 rabbits were killed, ca.1902-1910. More than 50 spectators look on outside the corral from horse-drawn carriages and on foot. Open source photo from USC Libraries Special Collections, University of Los Angeles, California.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, ethnographers visited Native American communities and recorded observations about daily life. They watched as the Akimel O’odham (formerly referred to as northern Pima), Tohono O’odham (formerly Papago), and Hopi conducted rabbit drives. It is thought that the techniques they used were also used by the people who have lived in the Sonoran Desert for thousands of years.

Akimel O’odham villagers, living along the Gila River near Phoenix, hunted rabbits in more open areas such as flatlands and bajadas. The best hunters would form into a horseshoe up to a mile and a half wide while others drove the rabbits into that area. The hunters then shot the rabbits with bows and arrows. The rabbits were killed, skinned, cooked, and consumed at the drive site. Any remaining rabbits were divided among the participants, taken home, and the meat dried for later use.

The Tohono O’odham in southern Arizona constructed an enclosure of brush fences with an opening where the shooters stood. Rabbits were chased towards the opening. Rabbit drives often occurred at the beginning of the rainy season and during the saguaro wine feast. Most of the captured rabbits were taken to the village and prepared for a feast which everyone was invited to attend.

Rabbit drives among the Hopi of northeastern Arizona were precipitated by the need to protect agricultural fields from rabbits. The hunts were often held prior to ceremonies, providing meat for feasting and also given to villagers. The hunters started by gathering in a two-winged circle formation approximately twenty-five yards apart. They beat the bushes as they walked towards the center of the circle. The rabbits were killed with throwing sticks as they were flushed out. In addition to their economic importance, rabbit drives also played a role in ritual activities related to farming.

Besides large concentrations of jackrabbit bones, evidence for these hunts has been found at several dry caves. Large hunting nets have been found in caves in southern Arizona, including the Baboquivari area, Texas Canyon, and the Cave Creek area in the Chiricahua Mountains. The Baboquivari area net was made with human hair and dates to the late Hohokam period. The other two nets were not datable, but could be from the historic period. All presumably were used in communal hunting. Deer could also have been captured in these nets. Explorer John Wesley Powell described how the Paiute hunted rabbits with a similar net. The net was placed in a semicircle with wings of sagebrush. The rabbits were driven into the net and shot with arrows.

Now we come back to the Yuma Wash site, where Desert Archaeology excavators working in the pit structure found the unusual layer of rabbit bones. The individual bones were more complete than the rabbit bone found in other features, and all portions of the skeleton were present. This is interpreted to represent the disposal of a relatively large number of jackrabbits in a very short amount of time. More jackrabbit bones were found than cottontail bones, also suggesting these bones were from a rabbit drive rather than from hunting these animals one at a time. After the hunt, the rabbits were cooked, stripped of meat, and the remnants thrown away into an abandoned pit structure, awaiting their future discovery by archaeologists.

Today we see cottontails hopping around Desert Archaeology’s office, and while out on survey we occasionally spot jackrabbits running away on their long legs. Many of their ancestors were once hunted during the Early Agricultural and Hohokam periods, providing the majority of meat consumed by these people.

Resources

To learn more about zooarchaeological analysis at Desert Archaeology, visit our Artifact & Specimen Analysis page.